Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Creating an Advantage in Global Capital Markets

The ABCP Crisis in Canada:

The Implications for the Regulation of Financial Markets

A Research Study Prepared for the

Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

John Chant

The ABCP Crisis in Canada:

The Implications for the Regulation of Financial Markets

Biography

John Chant

John Chant is Professor Emeritus of Economics at Simon Fraser University. He was educated at the University of British Columbia and Duke University and has taught at the University of Edinburgh, Duke University, University College Dar es Salaam, Queen’s University, and Carleton University. He has written extensively on a variety of topics including monetary policy and theory, financial institutions and their regulation, and issues in higher education. Mr. Chant has been Research Director of the Financial Markets Group at the Economic Council, Research Director of the Task Force on the Future of the Canadian Financial System, and Adviser to the Governor of the Bank of Canada. He has also served as editor of Economic Inquiry and Canadian Public Policy, and as a member of the Monetary Policy Council of the C.D. Howe Institute. He was awarded the Western Economic Association's Award for Teaching Excellence. Currently, Mr. Chant serves on the Editorial Board of The Fraser Institute and as a ministerial appointee to the Board of the Canadian Payments Association.

Table of Contents

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Features of the ABCP Market

- 3. The Regulation of ABCP Market

- 4. Causes of the ABCP Crisis

- 5. Policy issues

- 6. Conclusion

The ABCP Crisis in Canada: The Implications for the Regulation of Financial Markets

1. Executive Summary

Canadian financial markets were shaken in mid-August, 2007 when approximately $32 billion of non-bank, or third-party, sponsored asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) was frozen by the inability of the conduits to rollover their maturing notes. The affected conduits represented 27% of the $117 billion ABCP market. This paper examines the issues for the regulation of financial markets raised by the failure of non-bank sponsored ABCP conduits to rollover their debt.

The paper first examines ABCP market participants and the roles that they play. At the centre of the market are the conduits that issue ABCP and their sponsors. The ABCP note typically had a maturity of 30, 60 or 90 days and were backed up by liquidity arrangements that would enable the conduits to meet their repayment obligations under specified conditions, which for third-party conduits were dependent on a “general market disruption.” The assets held by third-party conduits were divided between traditional assets (29%) and synthetic, or derivative, assets (71%). Of the derivative assets, $17.4 billion (59% of total assets) were Leveraged Super Senior Swaps through which the conduits provided protection for others against credit losses.

In addition to the sponsors and their conduits, credit rating agencies and investment dealers and their sales representatives were critical to the market’s development. Credit rating agencies provided the rating that exempted ABCP from prospectus requirements and made it an eligible investment for many investors. Investment dealers and their sales agents distributed and marketed ABCP to financial institutions, pension funds, governments and their agencies, corporations, individuals and other investors.

The paper reviews the regulation governing the market’s participants in their ABCP activities. While the financial sector is one of the most heavily regulated areas of the Canadian economy, the ABCP participants were subject to minimal regulation with respect to their ABCP activities. The classification of ABCP itself as commercial paper exempted issuers from the need to issue a prospectus when their issues were rated by a credit rating agency. Canadian banks would have been subject to capital requirements against any unconditional lines of credit to ABCP conduits. Many liquidity providers were off-shore banks or non-bank financial institutions that were not subject to any capital charges for standby lines of credit provided to ABCP conduits.

The paper groups the causes of the ABCP crisis into core causes, magnifying influences and crisis triggers. The paper identifies the maturity mismatch in the structure of ABCP conduits, together with their risky derivative investments, as the prime causes of the crisis. Lack of disclosure by conduits of their business and the continuing favorable credit ratings tended to magnify the crisis. The US sub-prime crisis was the actual trigger of the crisis, but because of the inherent fragility of the ABCP market, other events, such as a rise in short-term interest rates, could also have sparked a crisis.

The paper raises a number of policy issues arising from the ABCP crisis. Prospectus exemptions, originally intended to apply to simple forms of commercial paper, were inappropriate for ABCP conduits that were heavily involved in writing credit derivatives. Similarly, the application of the same credit rating scale as used for other debt was unsuitable for ABCP. A favorable rating made ABCP an eligible investment for many investors and may have given comfort to others.

Some Canadian banks also sponsored ABCP conduits, holding them off-balance sheet so as to avoid capital requirements. Despite this, the banks provided support to their sponsored conduits when the crisis unfolded, calling into question the validity of the off- and on-balance sheet distinction. These actions may have shaped the ABCP crisis by avoiding a technical market disruption, denying the conduits support from their liquidity providers. The consequence is that it may have shifted the burden of losses to ABCP note holders and away from parties providing the liquidity arrangements.

The paper addresses the implications of ABCP crisis for both the content and approach taken to market regulation. The paper recommends, among other things, that:

-

i) prospectus requirements be based on an issuer’s activities;

-

ii) credit rating agencies register with securities authorities, adopt separate rating scales for structured products and make clearer the risks they cover;

-

iii) the banking regulator review the continuing suitability of on- and off-balance sheet distinctions for banking related activities with respect to regulatory capital requirements;

-

iv) the rules governing the sale and distribution of structured products reflect the characteristics of the product; and,

-

v) the communication among regulators should be reviewed to determine whether greater communication could prevent or reduce the severity of crises in the future.

The paper observes that market regulation balances rules and principles in practice and suggests greater scope for the use of principles-based regulation, in particular for prospectus and other distribution requirements; for determining on- and off-balance sheet activities of banks; and for rules governing the sale and distribution of financial instruments.

The ABCP crisis was both predictable and preventable. ABCP conduits were inherently fragile with their vulnerability further aggravated by the assets they held. While the ABCP market is unlikely to unfold again in the same way, this study has made recommendations that would make the nature of ABCP and similar innovations clearer to investors. Despite some added cost to market participants, the recommendations, if enacted, would make future crises less likely and less severe.

2. Features of the ABCP Market

(a) The “acquire-to-distribute” Model

The ABCP market can be characterized as being organized around the “acquire-to- distribute” business and represented a departure from traditional financing markets where commercial banks and other lenders operated an “originate-to-hold” business by making mortgages with the intention of holding them as investments. Much mortgage and other financing now take place under the “originate-to-distribute” model where lenders originate mortgages to sell them onward to investors. The originator’s function differs between the two approaches: the originator supplies finance and bears the credit risk in the former case and transfers both of these functions to the investors in the latter.

At the time of the crisis, the ABCP market in Canada had gone beyond the “originate/distribute” business. The non-bank, or third party, sponsors did not themselves originate all the assets held by their conduits. They functioned in what can best be described as an “acquire-to-distribute” mode: they acquired assets for the conduits from others who either originated the transactions or obtained them from others. In each case, distance between investors and the originators was lengthened.

(b) Participants

The participants in the ABCP market are shown in Table 2.1. They include the parties that establish and administer the vehicles, those that sell and distribute notes to investors, and those that provide stand-by liquidity in addition to the vehicles that hold assets and issue notes against them.

|

Table 2.1: Participants in the ABCP market |

|

|---|---|

|

Conduits |

Trusts that hold pools of assets and issue commercial paper backed by these assets |

|

Sponsors |

Establish conduits, select and administer the assets held by the conduit, and arrange for the sale of its issues of commercial paper |

|

Asset providers |

Supply loans and other claims to conduits |

|

Equity investors |

Invest in the equity of the conduit |

|

Distribution agents |

Sell the conduit’s commercial paper to investors |

|

Liquidity providers |

Supply liquidity to conduits under specified conditions |

(i) Conduits

At the core of the ABCP market are the conduits that issue notes, or commercial paper, against the security of a portfolio of assets. Conduits are trusts that are established by sponsors who administer the affairs of the trusts and assemble the assets held by the conduits. The conduits, subject to restructuring under the Montreal Accord (affected conduits), are listed in Table 2.2.

|

Table 2.2: Affected ABCP Conduits |

|---|

|

Apollo Trust; Apsley Trust; Aria Trust; Aurora Trust; Comet Trust; Encore Trust Gemini Trust; Ironstone Trust; MMAI-I Trust; Newshore Canadian Trust; Opus Trust; Planet Trust; Rocket Trust; SAT; Selkirk Funding Trust; Silverstone Trust; SIT III; Slate Trust; Symphony Trust; Whitehall Trust |

|

Note : Affected trusts also include associated satellite trusts Source: Pan-Canadian Investors Committee, Information Statement, p.156 |

(ii) Sponsors

Sponsors of conduits establish and manage the affairs of an ABCP conduit. They are responsible for arranging deals with asset providers, determining the terms of the program and acting as the agent for the programs with respect to securitization. Sponsors earn revenues by, among other ways, capturing the excess spread on assets acquired from the providers.

The sponsors of ABCP conduits include business corporations, which use the conduits to finance receivables generated by their business, banks and so-called third parties, which “specialized in structured finance using securitization-based financing technology.” [1] The third party sponsors of affected ABCP conduits are listed in Table 2.3.

|

Table 2.3: Sponsors of Affected ABCP Conduits and their Sponsored Trusts |

|---|

|

Coventree Capital Inc.: Apollo Trust, Aurora Trust, Comet Trust, Gemini Trust, Planet Trust, Rocket Trust, Slate Trust |

|

Quanto Financial Corporation: Apsley Trust, Whitehall Trust |

|

National Bank Financial: Ironstone Trust, MMAI-I Trust, Silverstone Trust |

|

Nereus Financial Inc. (subsidiary of Coventree): SAT, SIT III |

|

Newshore Financial Services Inc.: Aria Trust, Encore Trust, Newshore Canadian Trust, Opus Trust, Symphony Trust |

|

Securitus Financial Corp.: Selkirk Financing Trust |

|

Source: Source: Pan-Canadian Investors Committee, Information Statement, p.156 |

(iii) Liquidity providers

Liquidity providers are parties that have entered into agreements to provide standby liquidity to ABCP conduits (Table 2.4). Such agreements can differ in their conditions, with some unconditional and others conditional. Conditional agreements make the provision of liquidity dependent on a “general market disruption,” a condition that may be defined differently from agreement to agreement. Liquidity providers receive fees from conduits for providing stand-by liquidity arrangements.

|

Table 2.4 Liquidity providers to non-bank ABCP conduits |

|---|

|

ABN AMBRO Bank N.V. Canada branch; Bank of America N.A. Canada branch; Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce; Citibank Canada; Citibank N.A.Dansk Bank Deutsche Bank AG; HSBC Bank Canada; HSBC Bank USA; Merrill Lynch Capital Services Inc.; Merrill Lynch International; Royal Bank of Canada; Swiss Re Financial Products Corporation; Bank of Nova Scotia; Royal Bank of Scotland plc; UBS AG. |

|

Source : Pan-Canadian Investors Committee, Information Statement, p.168 |

(iv) Distribution agents

Investment dealers and sales representatives marketed the ABCP notes issued by conduits to investors (Appendix A).

(v) Credit rating agencies

Ratings from credit rating agencies were vital to the issue of ABCP through making them eligible for investors as a result of legal and institutional constraints on investors and to qualify them for exemption from the requirements to issue a prospectus. Initially, ABCP was rated by all three credit rating agencies operating in Canada: Dominion Bond Rating Service (DBRS), Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s. From 2000 onward, DBRS was the sole agency that rated third-party ABCP. [2]

(vi) Investors

The investors in ABCP included individuals, business corporations, financial institutions, public and private pension funds, governments and their agencies and universities together with about 1800 retail investors (see Appendix A).

(c) Assets of ABCP Conduits

(i) Assets

The assets underlying these ABCP claims were divided between traditional assets and synthetic assets (Table 2.7). Traditional assets were backed by instruments, such as mortgages, consumer loans, credit card receivables, commercial leases and other financial assets, and accounted for $8.4 billion of the assets backing affected conduits. Conduits accounting for $3.5 billion in assets held only traditional assets.

Synthetic assets are instruments backed by derivative contracts and accounted for approximately $21 billion (71%) of the assets of affected ABCP conduits. The synthetic assets included pools of Levered Super Senior Swaps (LSSS), a form of credit default swap, from which conduits received ongoing fees in return for its obligation to pay specified amounts if the underlying assets default. Changes in the reference on which the credit derivatives were based could trigger margin calls that would reduce the available collateral protecting the note holders. [3] The Leveraged Super Senior Swaps (LSSS) used leverage to increase the size of the commitment under a credit default contract. Under these contracts, the conduits were able to increase their commitments in credit derivative swaps beyond the amount committed to in the contract, magnifying both the fees they would receive and the risks that they would face. These contracts accounted for approximately $17.4 billion of the $21 billion in synthetic assets held by the conduits.

|

Table 2 .7 Assets Underlying Affected Conduits |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Type of asset |

Value (billion) |

Share of assets |

|

|

Traditional assets |

$8.4 |

28.6 |

|

|

Synthetic assets |

21.0 |

71.4 |

|

|

Of which Leveraged Super Senior Swaps |

$17.4 |

59.2 |

|

|

Total assets |

$29.4 |

100 |

|

|

Note: The assets fall short of $32 Third-Party sponsored ABCP reported in the Summary of Information. Source: Pan-Canadian Investors Committee, Information Statement, pp. 1-2 |

|||

(ii) Credit enhancement

Credit enhancement is a form of support to cover losses on a pool of assets held by ABCP conduits and was often necessary in order to gain a favorable credit rating for a conduit’s notes. Credit enhancement can take place through over-collateralization where the conduits hold assets with a value greater than the notes outstanding, through seller recourse or through guarantees, surety bonds, letters of credit or the presence of less senior notes issues.

(d) Notes of ABCP Conduits

The notes issued by the trusts differ with respect to their features. Series A notes are short-term (30, 60 and 90 days), their redemption at maturity is supported by liquidity arrangements, and they are rated by credit rating agencies. The series E notes generally have longer maturities (up to 270 days) and can be extended on maturity if the issuer is unable to repay. Series E notes are neither supported by liquidity arrangements nor are they rated by credit rating agencies. The pools of assets backing the series A and E notes are separate from each other. [4] Some conduits have offered notes other than series A and E that are typically junior tranches serving to insulate more senior notes against losses. Investment by equity holders may also provide over-collateralization protection to note holders by creating a buffer between the value of a conduit’s assets and its outstanding notes.

(e) Disclosure and Transparency in the ABCP Market

The disclosure to investors with respect to ABCP consisted of an information memorandum, a legal opinion and a report from a rating agency. Each will be discussed in terms of the information it provided and the usefulness of that information in disclosing the risks of ABCP to investors.

(i) Information memorandum

The information memorandum of a representative conduit consisted of six pages of text dealing with a broad range of matters likely to be of interest to investors. The information memorandum informed investors in series A notes about features of the trust:

-

securitized assets acquired by the trust could only be acquired from sources approved by the sponsor and the rating agency;

-

the sponsor was bound to exercise the same care as it would if acting on its own account;

-

the sponsor would monitor the performance of portfolios of securitized assets;

-

securitized assets acquired by the trust will be rated R1 (high) by the rating agency;

-

no acquisition will be permitted that would result in the reduction or withdrawal of the rating on already outstanding notes;

-

each class of notes is secured by separate assets;

-

the secured property at the time of any note issuance shall not have net negative asset value (as defined in the Trust Indenture);

-

credit enhancement may be provided for the notes issued by the trust;

-

liquidity agreements will be entered into prior to the issuance of any series A notes for the purpose of repaying these notes where there has been a market disruption; and,

-

the notes qualify as investments in statutes that govern banks, cooperative credit associations, insurance companies, pension funds, trust and loan companies and money market mutual funds.

The memorandum also alerts investors with respect to other features:

-

the assets of the trust are expected to change over time;

-

the issue of notes is unlimited “subject to the limitations and conditions set forth in the Trust Indenture and in any related supplements”;

-

the trustee will hold security interests on behalf of creditors including those who have provided credit enhancements;

-

none of the parties related to the trust guarantee the repayment of the notes or have any requirement to compensate note holders for any losses they realize (a caveat expressed in large, bold print); and,

-

the liquidity providers are not obligated to provide liquidity when the inability to repay maturing notes arises from the creditworthiness of the trust or the deterioration in the performance of its assets.

Despite the topics covered, this disclosure did not reveal many of the features that turned out to be crucial to the fate of ABCP issues.

As noted above, the discussion of the liquidity for series A notes stated that the trust could enter into agreements with liquidity providers approved by the rating agency requiring that they will make liquidity available “when a market disruption prevents [the trust] from issuing series A notes in the Canadian capital markets.” It also makes clear that the liquidity provider had no obligation to supply liquidity when a trust cannot issue series A notes. The memorandum did not, however, describe critical details of the liquidity arrangements, in particular the criteria for a “market disruption”. The memorandum stated only that the liquidity provider’s obligations were contained in the relevant liquidity agreement and in the Trust Indenture relating to the issue of the notes, documents not normally accessible to investors.

Similarly, the memorandum made only passing reference to the possibility of investment in credit derivatives and no mention of the exposure to leverage from holding such instruments. No mention was made of the conduits’ investments in Leveraged Super Senior transactions and the fact that these transactions had provisions that allowed the asset provider to call for additional collateral when the mark-to-market value of these transactions fell below a specified threshold. The only mention of investment in credit derivatives was the inclusion of “credit instruments” among the list of possible ownership interests for the trust.

(ii) Legal opinion

The legal opinion prescribed that the series A notes are eligible investments under the federal and provincial statutes governing a variety of classes of potential investors, including banks, cooperative credit associations, insurance companies, pension funds, governments and money market funds. The opinion also dealt with the eligibility of the extended notes (typically series E) for money market mutual funds.

(iii) Rating agency report

The rating agency report provided a separate source of information for potential investors and, in general, offered more detail than the information memorandum. It stated the current size of the program and the distribution of its assets among broad asset classes, including structured financial assets, uninsured residential mortgages and commercial mortgages. It noted that the rating agency was required to approve all transactions and described in general terms the credit enhancement arrangements, including the enhancer and the liquidity provisions and provider. It also provided a description of the assets the trust could hold, such as collateralized debt obligations.

Despite the added information, the rating report did not overcome the critical shortcomings of the information memorandum. It failed to provide critical details about liquidity provisions; credit enhancement; and the consequences of the trust’s Leveraged Super Senior transactions.

3. The Regulation of ABCP Market

The financial industry is one of the most heavily regulated industries in the economies of industrialized nations. In contrast to the rest of financial markets, the ABCP market and its participants when acting in this market are subject to minimal regulation (Table 3.1).

|

Table 3.1: The Regulation of Participants’ Activities in the ABCP Market |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Function |

Entity performing the function |

Regulation |

|

Issuer |

Conduit |

Securities Regulation (Canadian Securities Authorities) |

|

Sponsor |

Chartered Banks and Financial Companies |

None as sponsors of ABCP |

|

Credit rater |

Credit rating agencies |

None |

|

Liquidity provider |

Chartered banks |

|

|

Off-shore foreign banks and others |

None |

|

|

Sales and distribution |

Investment dealers and their sales representatives |

Conduct Regulation (IIROC); “Know your client” |

|

Investors |

Financial institutions, governments and their agencies, mutual funds, private and public pension funds |

Eligible investments |

(a) Issuers and Sponsors

(i) Issuers

Issuers of securities, including the ABCP conduits, are subject to provincial securities law under the authority of the provinces’ securities commissions. An important part of such laws are disclosure requirements through which most security issuers are required to file prospectuses with the relevant securities commission for approval and then make them available to prospective investors. Such prospectuses present comprehensive information about the issuer, including its history, the nature of its business and its financial condition. They also describe in detail the terms of the issue.

The prospectus requirements are waived under a variety of conditions, typically where the investor is assumed to be knowledgeable. For example, exemptions are made for private issues directed to a small number of sophisticated investors, often with specified minimum purchase amounts and levels of wealth.

Issuers of commercial paper are exempted from prospectus requirements under section 2.35 of National Instrument 45-106 – Prospectus and Registration Exemptions, if their issues have received an “approved rating from an approved credit rating organization.” This provision effectively delegates approval of all commercial paper issues, including ABCP, to the credit rating agencies. Through this delegation, credit rating agencies have become the sole certifiers of the eligibility of ABCP issues to go to market without a prospectus.

(ii) Sponsors

Bank sponsors

In addition to laws governing conduits as issuers, banks sponsoring ABCP conduits are subject to detailed, wide-reaching oversight and regulation over many aspects of their business. In practice, those activities that banks undertake directly on their balance sheets face comprehensive rules and regulations directed toward securing their safety and soundness. A major element of these rules is those specifying capital levels that banks must hold against specified assets.

Many activities undertaken by banks off their balance sheets are treated differently from on-balance sheet activities, as they are judged to be sufficiently separate from the banks as to not threaten bank soundness. As a result, these activities may not be subject to capital requirements. ABCP conduits have been treated as off-the-balance sheet of the sponsoring banks and did not have capital requirements.

Non-Bank sponsors

The non-bank sponsors, in contrast to banks, are usually not involved in financial activities that are subject to regulation. To insulate the affairs of the conduits from those of sponsors, conduits are arranged to be legally “bankrupt remote” from the sponsors.

(b) Credit Rating Agencies

Credit rating agencies serve many different functions in financial markets. They provide information to investors through reports and ratings; their ratings form the basis of laws, regulations and institutional rules that govern the eligibility of different securities for investment, and they provide advisory services to issuers. Despite performing these critical functions, credit rating agencies are generally not subject to regulation or oversight. Currently, Canadian authorities are participating in international efforts to have credit rating agencies conform to an industry code of conduct.

(c) Liquidity Providers

Until 2004, the liquidity arrangements between banks and ABCP conduits were treated by both OSFI and foreign bank regulators as being off-balance sheet and not being subject to capital requirements. At that time, OSFI announced a change that would require banks to hold capital against unconditional liquidity arrangements to ABCP conduits. They would not face capital requirements against so-called “Canadian style” liquidity arrangements drawable only in circumstances of a general market disruption. Liquidity arrangements between conduits and off-shore banks continued to be free of capital requirements as banking regulators in other countries did not generally follow OSFI’s lead. [5]

(d) Distribution and Sales

The distribution and sales of securities are subject to the dealer/member rules of the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC), a national self-regulatory organization of the securities industry that oversees all investment dealers and their registered employees.

Most transactions by investment dealers and their representatives with their clients with respect to the ABCP market are covered by “know your client” rules. The rule most relevant to the ABCP market states:

“Each Dealer Member shall use due diligence to ensure that the acceptance of any order from a customer is suitable for each customer on the basis of the customers’ financial situation, investment knowledge, investment objectives and risk tolerance.” [6]

Thus, investment dealers and their sales representatives bear a responsibility for assuring that clients’ investments are suitable to their needs. [7]

In addition to Rule 1300, IIROC’s Rule 1800 (Commodity Futures and Options) specifies the appropriate conduct for transactions in futures and options markets. Rule 1800 (2) requires investment dealers to designate principals for future contacts and futures options contracts that are responsible for assuring that the handling of transactions in these contracts conforms to IIROC’s rules and rulings. The principals, among other things, are required to use due diligence “to ensure that the acceptance of any order from a customer is suitable for each customer based on factors including the customer’s financial situation, investment knowledge, investment objectives and risk tolerance (Rule 1800.5 (a)). Unlike Rule 1300, there are no exemptions to the “know your client” rule in the case of transactions in futures contract and futures options.

(e) Regulation of Investors

Some investors, such as individuals and corporations, are totally unregulated in their choice of investments. For others, the eligibility is determined by the acts under which they operate (Table 3.2).

|

Table 3.2: Acts governing eligibility of ABCP as an investment |

|---|

| Bank Act (Canada) |

| Cooperative Credit Associations Act (Canada) |

| Insurance Companies Act (Canada) |

| Pension Benefits Standards Act, 1985 (Canada) |

| Trust and Loan Companies Act (Canada) |

| Financial Institutions Act (British Columbia) |

| Pension Benefits Standards Act (British Columbia) |

| Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund Act (Alberta) |

| Loan and Trust Corporations Act (Alberta) |

| Insurance Act (Alberta) |

| Financial Administration Act (Alberta) |

| Employment Pension Plans Act (Alberta) |

| The Pension Benefits Act, 1992 (Saskatchewan) |

| The Insurance Act (Manitoba) |

| The Pension Benefits Act (Manitoba) |

| The Trustee Act (Manitoba) (Subject to any express provision of the law or of the will or other instrument creating the trust or defining the duties and powers of the trustee) |

| Loan and Trust Corporations Act (Ontario) |

| Pension Benefits Act (Ontario) |

| Insurance Act (Ontario) |

| An Act respecting insurance (Québec) (for an insurer (as defined therein) constituted under the laws of the Province of Québec, other than a guarantee fund) |

| An Act respecting trust companies and savings companies (Québec) (for a trust company (as defined therein) investing its own funds and deposits it receives and a savings company (as defined therein) investing its own funds) |

| Supplemental Pension Plans Act (Québec) (for a plan governed thereby) |

| Trustees Act (New Brunswick) |

| Pension Benefits Act (Nova Scotia) |

| Insurance Companies Act (Newfoundland and Labrador) |

| Pension Benefits Act, 1997 (Newfoundland and Labrador) |

| National Instrument 81-102 |

(f) Organization of Regulation

The participants in ABCP are subject to a variety of regulators (Table 3.3). In one way or another, the regulators of some aspect of the ABCP market include OSFI (for banks as sponsors, liquidity providers and investors, insurance companies as investors and federal pension funds as investors), provincial securities commissions (for conduits as issuers), IIROC (for investment dealers and their representatives as distributors and sellers) and financial regulators (for financial institutions and provincial pension funds as investors).

The Heads of Agencies (HOA) provides an informal forum that brings together the Governor of the Bank of Canada, the Supervisor of OSFI, the federal Department of Finance, and the heads of the B.C., Alberta, Ontario and Quebec securities regulators. The HOA meets quarterly to discuss issues of common concern. While it provides a venue for the exchange of information, it is not known the degree to which participants shared concerns about the ABCP market.

The organization of financial market regulation differs substantially between Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States (Table 3.3). Overall, the UK has a much greater consolidation of regulatory authority than Canada. With the exception of the Bank of England’s responsibility for financial stability, both the prudential and the market conduct regulation of securities market participations and financial institutions are centralized in the Financial Services Authority. The US has a mixture of centralization and dispersion of authority. The authority over financial intermediaries, such as banks or thrift institutions, is spread among the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Controller of the Currency (part of the Treasury), the Office of Thrift Supervision and state agencies. In contrast, virtually all responsibility for securities market activities, including the regulation of credit rating agencies, is centralized at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

In Canada, like the other countries, financial stability is the responsibility of the central bank. Unlike the US and like the UK, banking regulation is not undertaken by the central bank but by a separate agency, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI). Canada, unlike the others, has separate agencies dealing with market conduct and prudential regulation in securities markets. Responsibility for prudential regulation of securities markets is shared by provincial authorities.

Recently, authorities in both the UK and US have been concerned about achieving the proper division of responsibility among their various regulators. The UK consolidated regulatory responsibility in its Financial Services Authority in 2000 most notably by transferring the responsibility for the banking industry away from the Bank of England. In the United States, the Treasury has recently recommended sweeping changes that would alter the structure of regulation. In Canada, the issue was made part of the mandate of the Expert Panel.

|

Table 3.3 Division of Regulatory Responsibilities: Canada, United Kingdom and United States |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Type of activity |

|||||

|

Credit rating agencies |

Securities markets |

Banking |

Financial stability |

||

|

Distribution and sales |

Securities issuance |

||||

|

Canada |

None |

IIROC |

Provincial securities administrators |

OSFI |

Bank of Canada |

|

United Kingdom |

None |

Financial Services Authority |

Bank of England |

||

|

United States |

Securities and Exchange Commission |

Federal Reserve |

|||

|

FDIC OCC OTS State agencies |

|||||

4. Causes of the ABCP Crisis

The ABCP crisis in Canada and elsewhere has been attributed to a variety of influences contributing to the crisis (Table 4.1). Some can be viewed as the root causes of the instability, others magnified instability already inherent in the ABCP market; and still others were triggers precipitating the crisis. Some magnifying influences did so before the crisis (pre-crisis influences) by increasing the buildup of a fundamentally flawed market and others heightened the severity of the crisis once it began (post-crisis influences). This section discusses the core causes, some of the magnifying causes and the trigger.

|

Table 4.1: Influences on the ABCP crisis in Canada |

|

|---|---|

|

1. Root causes |

|

|

Fragile structure |

|

|

Unsuitable investments ( levered credit derivatives) |

|

|

2. Magnifying influences |

|

|

a) Pre crisis influences |

|

|

“Originate to distribute” model |

|

|

Favorable credit ratings |

|

|

Exemption from prospectus requirements |

|

|

Eagerness of investors for higher returns |

|

|

Under pricing of risk [8] |

|

|

Failure of sales representatives to understand the ABCP product |

|

|

Failure of sales representatives to follow “know your customer” rules |

|

|

Faulty risk modeling by credit rating agencies and institutional investors [9] |

|

|

b) Post crisis influences |

|

|

Lack of transparency of conduits |

|

|

“Originate to distribute” model |

|

|

Conditional liquidity arrangements |

|

|

“Mark to market” accounting |

|

|

4. Triggers |

|

|

Condition of US Sub-prime market |

|

(a) Primary Cause: Unstable Business Model

(i) Structure

A primary cause of the crisis in Canada was the fragility of the business model inherent in the conduits that issued ABCP. These conduits were financed by issuing fixed value short-term notes against their longer term assets, producing a maturity mismatch between their liabilities and assets. In addition, they were heavily levered with only limited equity to provide a protective cushion for note holders. These two features left them vulnerable to “runs” where investors would not purchase new issues to replace maturing notes because of concerns about the conduits’ abilities to meet their future obligations. Experience shows that such concerns can be self-realizing: if investors’ shun new note issues, conduits will eventually be unable to repay their maturing notes. It does not matter whether the investors’ fears are justified or not, in either case the conduit would be unable to repay its notes.

The ABCP business model has led to frequent crises over the history of financial markets. The early history of banking provides many examples of bank runs where depositors rushed to withdraw their funds from banks, often forcing them out of business. In addition, once depositors doubted the soundness of one bank, the doubts could spread to others, creating a chain reaction that could threaten the stability of the entire banking system. The possibility of these runs in the banking industry has been reduced by such measures as deposit insurance, central bank lender of last resort facilities, and the regulation and supervision of banks.

Runs have not just been confined to the banking industry. Any financial business based on using short-term borrowings to fund longer term assets can be vulnerable. The experience of real estate mutual funds in Canada during the 1990s provides a further example. Several of these funds were organized as “open-ended” mutual funds where unit holders could withdraw their funds at specified times at a price based on the most recent appraisal of the fund’s properties. The appraisals were carried out over a two-year cycle and at any time could differ from the current values. When a downturn in the property market created discrepancies between the market value and the appraised value, many investors acted to withdraw their investments on terms based on the higher out of date appraisals. [10] Eventually, the outflows became so great that the funds were forced to freeze their redemptions. [11]

The instability identified with ABCP does not appear to be a problem for other types of commercial paper. Despite questions of creditworthiness with respect to specific issuers, never has there been a prolonged general market disruption with respect to commercial paper issues by businesses. Similarly, the same instability has not appeared in simple mortgage vehicles with matched maturity between assets and liabilities that have existed in Canada since the 1960s.

The design of ABCP conduits made them vulnerable to runs. If instead the conduits had financed themselves though longer term issues, the crisis might have been avoided. Still, the absence of maturity mismatches would not have protected investors from losses. Rather the value of the conduit claims in the market would have fallen with their funding intact. Investors would have still suffered losses, but the absence of maturity mismatches would have averted the scramble to exit that brought the market down, and left investors frozen into ABCP.

(ii) Assets held

The investments held by the ABCP conduits were also a prime cause of the crisis. Most notably, ABCP conduits, in addition to holding traditional assets, held a substantial proportion of their assets in credit derivatives. By writing derivatives, the conduits received fees in return for accepting obligations to compensate others for losses suffered from exposure to specified risks. Further, they used derivatives to assume the risks of underlying securities that were a multiple of the stake they put up. Any investment vehicles that, like the ABCP conduits, held 60 percent of its portfolio in levered credit derivatives would be extremely vulnerable to credit market developments. The asset holdings of the ABCP conduits just added to the vulnerability of an already fragile financial structure. [12]

(b) Magnifying Influences: Pre Crisis

(i) Acquire-to-distribute model

Many have cited the so-called “originate-to-distribute” business model as a factor contributing to the scale of the ABCP crisis. This approach freed ABCP sponsors from their own ability to originate by allowing them to buy assets from lenders in many markets, including the US sub-prime mortgage market. On this basis, non-bank sponsored ABCP grew from just 15 percent of the ABCP market in 2004 to 48 percent of the $117 billion of the ABCP market at the end of 2006, increasing the eventual scale of the crisis.

(ii) Credit ratings

The size and growth of the ABCP market depended on gaining favorable ratings from credit rating agencies. Such ratings allowed ABCP issues to be exempted from prospectus requirements and also qualified them as eligible investments for many investors. Many investors appear to have relied on the judgment of credit rating agencies in light of the limited public information about ABCP.

Credit rating agencies have been criticized for failing to detect and alert investors of the weaknesses of ABCP offerings before the crisis broke out. Such criticism is understandable: agencies had privileged information not available to investors and claimed that, as part of the rating process, they reviewed and approved transactions undertaken by the issuers.

The major rating agencies in Canada took different approaches to the rating of ABCP. Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s ceased offering ratings once ABCP conduits adopted “Canadian style” liquidity provisions conditional on “general market disruption.” The sole ratings for Canadian ABCP issues from that time onward were offered by the Dominion Bond Rating Services (DBRS), which stopped rating new ABCP trusts in January 2007 and removed its ratings of non-bank sponsored trusts in May 2008 at the request of the trusts themselves, long after the unfolding of the crisis in August 2007. [13]

Some suggest that criticisms of the rating agencies may be overstated because of a misunderstanding of their role. IOSCO’s Technical Committee and others, including the agencies themselves, contend that credit rating agencies are concerned with credit risk and credit risk alone:

“The rating represents an opinion as to the likelihood that the borrower or issuer will meet its contractual, financial obligations as they become due…It does not address market liquidity or volatility risk (IOSCO, Role of Credit Rating Agencies, p.3).”

This view is echoed in DBRS’s statement of rating philosophy:

“[i]n general terms, ratings are opinions that reflect the credit worthiness of an issuer, a security, or an obligation…Ratings for structured finance vehicles reflect an opinion on the ability of the pooled assets to fund repayments to investors according to each security’s priority of payments.”

“DBRS believes that investors will use its ratings to assist them in gauging credit risk and better understand the issuer and the security in question (DBRS, Rating Philosophy).”

The agency explicitly warns that, in addition to the credit risk on which it makes its ratings, non-credit risks, such a market risk, liquidity risk and covenant risk, can contribute to the overall risks of holding structured investment products.

The distinctions between the types of risk are not as clear cut as these agency’s statements suggest. For tradable bonds, liquidity risk is quite different from credit risk and reflects the ability to sell the bonds easily. It is a statement about the quality of the market and the possibility of disruption in that market. This type of liquidity risk is not relevant for ABCP: investors generally do not intend to resell them in secondary markets because of their short maturity and look toward the issuer to redeem the commercial paper at maturity.

The liquidity problems that bedeviled ABCP issues differed from those faced by bond holders and arose from the issuers’ inability to fund their maturing obligations. The crisis was precipitated by the issuers’ failure to repay their notes on schedule – the essence of credit risk. It was concern about liquidity protection and the resulting inability of ABCP conduits to repay their notes and not credit risk (narrowly defined) that caused Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s to discontinue rating Canadian ABCP. [14]

(iii) Prospectus exemption

The exemption from prospectus requirements worked to increase the size of the crisis. Favorable credit ratings signaled to investors, whatever the intentions of the rating agencies, that investments in ABCP conduits were safe. Investors familiar with the rating scale from its application to other debt could expect it to have the same meaning for ABCP. Further, a favorable rating was a condition for exemption from prospectus requirements. Both of these factors fostered the perception that ABCP issues were safe. Without these, the ABCP market could not have grown the way it did because many investors would have been restrained by laws, institutional practices or an unwillingness to invest in an “uncertified” security.

(iv) Distribution and Sales

The actions of some sales representatives of some investment firms also affected the size of the ABCP crisis. Even though representatives are obliged to respect “know your client” rules, evidence suggests that some induced investors to acquire ABCP issues in belief that they were safe investments. [15] The case of the 1800 small investors in ABCP appears to be a failure by their sales representatives to meet this obligation. But even sophisticated investors appear to have acquired ABCP in conditions where the favorable yield difference did not justify the risks. To the extent that sales representatives actively promoted ABCP, the resulting purchases expanded the size of the ABCP market and increased the magnitude of the crisis once it occurred.

(v) Investors’ appetites for risk

Investors’ appetites for ABCP issues were intensified by the existing conditions in financial markets. High savings levels throughout the world together with smaller net issues of government securities in Canada combined to limit attractive investment opportunities in fixed-income securities, leading investors to search for higher yields. The introduction of new structured products took place at a time when investors were receptive to securities offering even slightly higher returns than the safest securities, favoring the rapid growth of the ABCP market.

(c) Magnifying Influences: After the Fact

(i) The “acquire-to-distribute” model

The acquire-to-distribute approach also affected the severity of the ABCP crisis once it started by having added additional layers separating the originators of the claims from those who ultimately financed them. Any slippage in assessing loan quality arising from this separation of functions would be accentuated by the greater degree of separation in the financing process. The separation also contributed to the lack of transparency.

In the case of mortgages, the underlying loans could be sold with other mortgages as part of a package assembled by the originator. This package then could be sold to an acquirer who combined that package with other packages that were sold onward together to the ABCP sponsor. At all stages, the packages may also have been sliced into tranches with different priorities in case of default. Any determination of the quality of the assets underlying the packages acquired by the ABCP sponsor would require unraveling the chain down to the individual loans and determining the conduit’s stake in each. As doubts arose with respect to sub-prime mortgages, and their place in ABCP holdings, large ABCP investors took actions to freeze the ABCP market in part on the basis of their fears about the quality of the underlying assets.

(ii) Liquidity arrangements

As discussed earlier, conduits could draw on their liquidity lines only under the condition of a general market disruption, a limitation that meant a conduit could not expect support if it were either the only conduit, or even if it were one of a group of conduits, unable to rollover its notes. As it turned out, the inability to demonstrate a “general market disruption” at the onset of the crisis left non-bank conduits unable to draw on their liquidity lines, effectively freezing their investors’ claims.

In absence of conditions on liquidity lines, the crisis may have developed differently. Some note holders may have been repaid, shifting losses toward the liquidity providers and credit enhancers. Possibly the ability of the conduits to repay maturing notes could have changed the way the crisis played out or even averted it.

(iii) Lack of disclosure

Once investors became aware of the weakness of the ABCP market and lost confidence in it, they reacted swiftly to withhold further investments because they could not judge the risk of the conduits. The lack of transparency prevented investors from differentiating among ABCP conduits. The general run on all conduits may have brought down conduits that could have continued if investors had a clear understanding of each conduit’s asset composition and quality.

(d) Triggers

The abrupt crisis that hit the ABCP market was precipitated by a collapse of investor confidence that followed closely on US developments that progressively revealed the weakness of the sub-prime mortgage market. Through the months leading up to the freeze on the conduits’ assets, New Century, a large sub-prime mortgage lender filed for bankruptcy (April 3); two Bear Stearns hedge funds did the same, citing deterioration in the value of sub-prime holdings (July 31); a German bank was bailed out by another bank due to exposure to US sub-prime loans (August 2): BNP froze three funds due to sub-prime losses (August 9) and both the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve acted to expand credit lines to banks because of widespread liquidity shortages (August 9). [16] Non-bank ABCP sponsors claimed a “market disruption event” at the close of business on August 13. The growing US sub-prime crisis proved to be the catalyst that set loose the Canadian ABCP crisis.

While the sub-prime crisis was the actual shock that destabilized the Canadian ABCP market, the market was vulnerable to other possible shocks, such as a general rise in interest rates. The conduits held many assets with fixed interest rates that could respond to higher market rates only after a lag. In refinancing their maturing notes, the conduits would have had to compete with instruments offering the current market rates. Any significant movement of market rates would squeeze or wipe out the conduits’ margins and leave the conduits unable to refinance themselves, or if not, raise investors fears, creating a crisis much like the one that took place.

Emphasizing the US sub-prime mortgage market as the cause of the ABCP crisis distracts from the lessons that can be drawn from the experience. The sub-prime crisis was a shock. But, the ABCP market was inherently fragile and highly vulnerable to many possible shocks. The US sub-prime crisis was one shock among others that could, and in this case did, expose the fragility of the underlying business model. But, overall, the sub-prime difficulties should be viewed as the trigger that brought down already unstable investment vehicles.

5. Policy issues

(a) Disclosure

The adequacy of disclosure for ABCP has been questioned by many observers of the crisis. Since ABCP and the trusts that issue them are much more complex than traditional commercial paper, it might be expected that the sponsor would provide a more comprehensive disclosure of information to allow investors to make informed decisions. To the contrary, the ABCP sponsors provided only limited information with scant details of critical provisions. In commenting on the disclosure with respect to one type of asset holding, JP Morgan concluded:

“Many potential and current investors did not have specific asset information related to the Leveraged Super Senior credit default swaps, making it difficult to predict or estimate the credit risk and the likelihood of a Margin Call.”

This lack of transparency, they argue, was a contributing factor for the diminished investor appetite for ABCP once markets started to deteriorate. In general, the information provided to potential investors was inadequate to inform them of the size and the nature of the risks they faced through investing in ABCP.

Several questions need to be addressed in light of inadequate disclosure: Should the current exemption of commercial paper from prospectus requirements be modified, or even eliminated? How should this provision be modified? To the extent further disclosure is required, should it be prescribed by rule or based on principle?

The exemption of commercial paper from prospectus requirements may have been suitable for all issuers at one time and may still remain suitable for some today. The ABCP of the last half decade bears little resemblance to the commercial paper of the past. ABCP was issued by conduits created to issue commercial paper against asset holdings. Typically, the conduit’s assets were:

-

opaque to investors;

-

often composed of portfolios of securitized assets;

-

supplied by multiple asset providers;

-

often included synthetic derivative securities;

-

were often highly levered;

-

subject to changes in composition between asset classes; and,

-

subject to changes within classes of assets.

In addition, few details were provided by the sponsors with respect to the terms and conditions of the liquidity lines and credit enhancements, features that ostensibly protect investors’ interests.

While elimination of the exemption for commercial paper would be the simplest solution, such a blanket removal of exemption is unnecessary and would be detrimental by adding to the costs of all commercial paper issues. Continuation of the exemption for simpler forms of commercial paper would play a useful role by facilitating these issues.

The current exemption from prospectus requirements is inappropriate for the types of instrument represented by ABCP. Securities regulators need to review the prospectus exemption for commercial paper both in terms of its purpose and application. Such a review should lead to a restated prospectus exemption combining elements of both principle-based and rule-based regulation. Principles are needed to make clear the basis of the exemption and to preempt technical avoidance of the rules that is outside the spirit of exemption. Rules are needed to set out the criteria by which security issues are to be exempted for prospectus requirements. Each of the nature of assets held, the relation of the originator to the issuer and the type of issuer, could be used as criteria for determining the exemption from prospectus requirements.

Recommendations:

-

Exemptions from prospectus and other distribution requirements should be based on principle, according to the nature of the activities being undertaken.

-

The prospectus exemption for commercial paper should be reserved for single source issues holding traditional assets.

-

The basis for exemption should be regularly reviewed by the relevant authorities to determine its continuing appropriateness.

(b) Credit Rating Agencies

Some critics of credit rating agencies suggest that problems such as those revealed by the ABCP crisis are inherent in the business model they use. The agencies depend on fees paid by prospective issuers seeking ratings for a significant source of their revenue. At the same time, they also offer guidance to sponsors to enable them to get the ratings that would make their conduits attractive to investors and, for some, eligible investments. The IOSCO Technical Committee points out that the process for rating structured assets reverses that for more conventional products: the issuer decides on the desired rating and structures the product accordingly, often with the advice of the credit rating industry. [17]

Dissatisfaction with the performance of credit rating agencies has spawned reforms ranging from measures that would reshape the industry to fine tuning of industry practices. Among these reforms are the following:

- making investors rather than issuers pay for credit ratings;

- greater transparency in ratings;

- creating a separate ratings scale for structured products;

- banning an agency from rating products for which it has provided advice; and

- increased regulation of rating agencies. [18]

(i) Making investors pay for ratings

Ratings agencies currently gain roughly 90 percent of their revenues from fees charged to issuers. [19] Many view this major dependence on revenues from issuers to pose a conflict of interest. Some suggest that the conflict could be avoided by having investors pay for ratings as they did up to the 1970s. With the wider use of ratings and innovations in communications, ratings have become public goods in that people can gain access to them readily without paying for them (Zelmer, 2007). Having users pay for ratings may no longer be practical or even possible.

(ii) Greater transparency in ratings

The complexity of structured products makes it difficult for investors to properly assess their risk. In order to so, investors need:

“To gauge the credit risk of the underlying (heterogeneous) collateral assets but also to have sufficient insight into the legal structure and the specific provisions of the transaction…that organize the different seniority levels of the tranches (CESR, May 2008, p.8).”

Such insight is difficult under the past disclosure policies of ABCP issuers and the credit rating agencies.

As an approach to remedying this lack of transparency, the Bank of England, for example, has recommended that disclosures of rating agencies with respect to their ratings of structured products include:

- expected loss distributions of structured products;

- a summary of the information provided by the originators of structured products;

- explicit probability ranges for their scores on probability of default;

- adoption of the same scoring definitions; and,

- scoring instruments on dimensions other than credit risk. [20]

These disclosures would facilitate better understanding of the basis through which credit ratings are determined.

Still, the need for disclosure goes well beyond the techniques used for rating ABCP. Credit rating agencies have privileged access to information about structured products relative to investors. They approve transactions and rule on the adequacy of liquidity lines and arrangements for credit enhancement. As a result, they know the composition of the vehicle’s assets, its use of derivatives, and the details of covenants that could impair the claims of investors. Despite the agencies’ superior access to details of the critical features of the conduits they rate, few of these details reach the reviews that accompany their ratings. These reviews are sparse and lack the depth necessary to inform investors. The agencies also use conditional and vague language that could be consistent with many interpretations.

The privileged access of rating agencies goes hand in hand with an obligation of confidentiality. Such an obligation may be justified when issuers wish to protect information for competitive reasons. At present, the balance seems too far to confidentiality and too little toward the interests of investors.

(iii) Separating rating from advising functions

The combination of the dual function of credit rating with advisory services to issuers in the same agency has been a source of concern with bodies such as the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). This concern was reflected in IOSCO’s inclusion of a conflict of interest provision in its code of conduct for credit rating agencies:

“The CRA should separate operationally, and legally, its credit rating business and CRA analysts from any other businesses including consulting businesses that may present a conflict of interest.” [21]

DBRS initially responded to this provision by declaring that rating was its only business and that it does not engage in consulting or advising, a response that CESR judged as non-compliant with the provision. Subsequently, DBRS replied that it “may provide an impact assessment at an issuer’s request” and that it “views this work as an extension of its existing relationship with the issuer and not as a separate business line. [22] DBRS further asserted that it did not believe that using the same team of analysts for the two activities was a conflict of interest. CESR took the view that rating impact assessment services were an ancillary activity and judged that DBRS failed to comply with the conflict of interest provision of the IOSCO code.

(iv) Establish separate rating scale for structured products

The proposal that structured products be given separate credit ratings from other debt offering reflects the recognition that structured products differ substantially from the corporate debt traditionally evaluated by rated agencies (Table 5.1).

|

Table 5.1 Differences between corporate bond offerings and structured products |

|

|---|---|

|

Corporate debt |

Structured products |

|

Organized to carry out business activity |

Organized according to “originate (assemble) to distribute” model |

|

Issued against corporate assets as part of an overall financial strategy that includes bank loans, short- and long-term dent and equity |

Issued against a stand-alone vehicle which has the sole purpose of holding assets and issuing claims against them |

|

Often trade in secondary markets where prices are set |

Do not trade |

|

Payments to investors supported by cash flows from corporation’s operations |

Payments to investors supported by cash flows from asset holdings |

|

Require prospectus except for commercial paper |

Exempt from prospectus requirements |

|

Rated issues “by analyzing relevant information available regarding the issuer or borrower, its market and its economic circumstances” [23] |

Rated on basis of collateral underlying the issue |

|

Comprehensive public disclosure in corporate filings and prospectuses |

Limited disclosure in information memorandum |

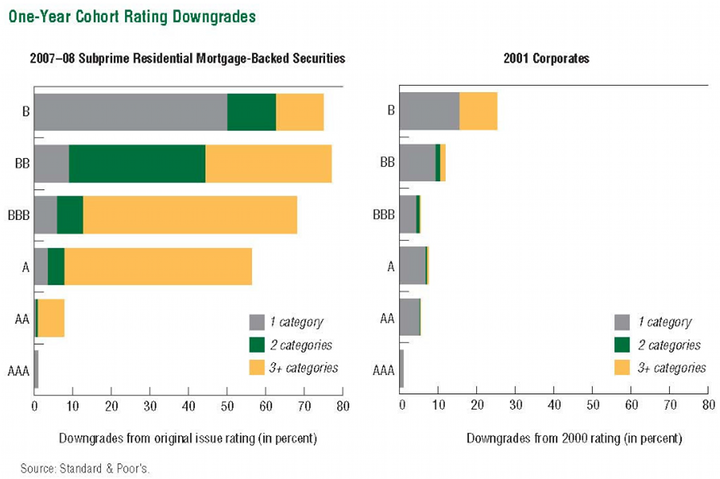

The differences between corporate issues and structured products go beyond their characteristics and are reflected in their rating experience. Chart 5.1 shows that structured products experience more frequent and more severe downgrades in times of stress than bonds issues with the same rating. In other words, rating agencies have been less capable of foreseeing the future conditions of structured products than they have for conventional debt issues.

Structured products are sufficiently different from conventional debt to make it appropriate to rate them according to a separate scale from corporate debt. A separate rating system for structured products would alert investors that structured products pose different risks. It could also induce regulators to reconsider the treatment of these products, especially in terms of exemptions from prospectus requirements. Such a rating system could also benefit investors if credit rating agencies, in making a separate scale, took the opportunity to emphasize features, such as liquidity and credit enhancement, critical to the risks of structured products.

Chart 5.1:

Experience of rated US bonds and mortgage backed securities

Source: IMF, Financial Stability Review

(v) Increased regulation

In general, credit rating agencies are not subject to regulation or oversight. In an exception, the U.S. requires credit rating agencies to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Recently, US authorities have re-evaluated the oversight of the Commission’s role with respect to credit rating agencies in response to the corporate scandals of 2001 and 2002, leading to the recently passed Credit Rating Agency Reform Act that required credit rating agencies to establish procedures to prevent the misuse of material, non-public information and to address and manage conflicts of interest.

Several developments have taken place elsewhere short of regulation. IOSCO has established an extensive voluntary code of conduct for credit rating agencies. The degree of compliance with this code by major rating agencies has been monitored and reported on by CESR, which recently recommended taking the process further through the establishment of “an international CRA standard setting and monitoring body to develop and monitor compliance with international standards.” [24]

Moreover, the CESR recommends that the EU act alone in moving forward if the proposed international initiative does not progress in the short run. Finally, and significantly, if the body fails to meet its objectives of “integrity and transparency in ratings”, the CESR advocates that supervisory authorities should probably use explicit regulation to achieve the objectives.

The appropriate regulatory treatment of credit rating agencies depends on the perspective from which they are viewed. An information perspective suggests that agencies help investors in overcoming their information disadvantages relative to the issuers. In effect, a credit agency gathers and interprets information more efficiently than individual investors could by acting on their own. Agencies have taken the position that they are on a par with financial journalists in providing information to investors when defending themselves from legal liability from their ratings. [25] A certification perspective suggests that ratings provide credentials to issuers that broaden their range of investors for their issues by satisfying either legal eligibility requirements or institutional norms. They also perform a further certification role in Canada by making issuers eligible for prospectus exemptions.

From the information perspective, credit ratings are just one source of information to potential investors, giving little justification for regulation. The certification perspective places credit ratings as part of the regulatory apparatus for financial markets. The two different perspectives on credit rating agencies carry quite different implications for the status of credit rating agencies and have contributed to ambiguity about the need for regulating them. The legal and institutional recognition of credit ratings creates an obligation for the rating agencies. As discussed earlier, the ABCP experience suggests that one Canadian credit rating agency and its procedures fell short of the standards appropriate to their position.

Any call for increased supervision and oversight of credit rating agencies should be taken with care. The approach to regulation must distinguish between areas where regulation can make a contribution and areas where it could be detrimental. The approach taken should focus on the organization and transparency of the agencies and not the specific methods and techniques by which they rate issuers.

Stéphane Rousseau has proposed a reasonable approach to the supervision and oversight of credit rating agencies in a study for the Capital Markets Institute. He suggested that credit agencies be required to register with securities commissions. This registration could provide for some reform of the credit rating industry without creating the overhead of a new regulatory mechanism. For example, registration could be made conditional on compliance with a code of conduct. While the IOSCO code provides a useful starting point, securities regulators should be open to hearing arguments with respect to the suitability of the provisions of the code.

Recommendation:

-

credit rating agencies should be registered with securities administrators in order to gain “approved” status,

-

registration of credit rating agencies should be conditional on their acceptance of a code of conduct based on the principles of the code adopted by IOSCO,

-

regulatory agencies should require a separate rating scale for structured products for determining investment eligibility and other purposes for which ratings are required,

-

credit rating agencies should include clear statements of the risks covered as part of their ratings reports,

-

Canadian securities administrators should participate in international discussions with respect to the registration of credit rating agencies but should proceed on their own if international efforts do not proceed sufficiently.

(c) Banks

The ABCP market involved banks in a variety of ways. Some ABCP conduits were created and sponsored by banks. Banks also provided these conduits with lines of liquidity and credit enhancement facilities. The different degree of bank identification with and involvement in the conduits may have shaped the ABCP crisis in Canada and its effects on different parties.

This section begins with a review of the place of banks in the Canadian economy as background for understanding their relation to the ABCP market and its implications. It then describes the ways in which banks participate in the ABCP market and discusses the ways in which the participation in this market shaped the ABCP crisis and its impact on different parties.

(i) Banks and the economy

Banks occupy a special place in any economy because their deposits provide a safe investment for the public and also serve as the main medium for making payments. While a large share of deposits can be redeemed on demand or short notice, many of the assets held by banks are effectively illiquid in the short run. Because of this difference between banks’ assets and liabilities, banks perform a so-called intermediary function that allows their depositors to satisfy their desire to hold short-term liquid claims and their borrowers to have greater certainty about the stability of their financing. [26] The viability of banking depends vitally on maintaining the depositors’ confidence that they will be repaid when requested.

Governments have long recognized both the critical role of banks in the economy and their inherent fragility by establishing both a regulatory framework and a safety net to protect the soundness of banks. The regulatory framework includes capital requirements and regulatory oversight for the purpose of limiting the risk posed by the banking system. The safety net includes special borrowing facilities from the central bank and deposit insurance backed up by government guarantees.

(ii) Banks and the ABCP market

The banks first participated in securitization by assembling claims acquired through their lending and distributing them to other investors. Usually this type of securitization was simple and transparent because the bank’s receivables were packaged into trusts that contained only one type of asset from a single source, the bank itself. Securitization allowed banks to earn revenue from originating and servicing the receivables while having them financed by others. In addition, the financing of these receivables would not be subject to capital requirements as they would have been if financed by the banks directly.

Subsequently, banks’ participation in the ABCP market evolved from simple securitization. Some bank ABCP issues utilized the acquire-to-distribute model whereby sponsoring banks acquired assets for the trust from other sources and placed more than one type of asset in the trusts.

Banks were also involved in facilities essential to the viability of third-party ABCP conduits. They supplied the lines of liquidity support and credit enhancement facilities, both of which were required to qualify the conduit for a favorable credit rating.

(iii) Bank regulation and the ABCP market

Canadian bank regulation has influenced the development of the ABCP market in several ways. Participation in securitization was in part a means by which banks were able to minimize their regulatory capital. Regulation also influenced the way in which banks served as liquidity providers.

Capital requirements and ABCP

Bank capital requirements make distinctions according to a bank’s exposure to risk. Assets held on a bank’s balance sheet are subject to capital requirements while those moved off-balance sheet, into separate arm’s length entities where banks do not have legal responsibilities for losses, were not. It was this difference that made securitization attractive to banks. The ABCP market provided banks with the opportunity to earn revenues from pools of assets while reducing the capital that would be required if they held them on their balance sheets. Instead of the interest that would be earned from holding the assets, they gained revenues from their role in packaging and servicing the assets held by the vehicles.

As the ABCP crisis unfolded, banks realized that failure to support their conduits would harm their reputation and supported their sponsored conduits, despite having avoided capital requirements against them up to the time of the rescue. They effectively negated the intent of the capital requirements. As OSFI has observed,

“The risk has not been transferred to investors, therefore challenging the theory that banks could transfer risk to another party, which was the underlying rationale for zero capital charges on liquidity lines to ABCP conduits.” [27]

The banks were apparently able to support their sponsored conduits by using an “implicit recourse” provision that permits a parent bank to “provide support to an [investment vehicle] that exceeds its ‘contractual obligation’ to preserve its ‘moral’ standing and protect its reputation.” [28] Such support may have been justified as necessary for preventing the ABCP crisis from spreading into a more general banking crisis. The Canadian banks were in a relatively strong capital position at the time so that the rescue appears to have raised few concerns about their soundness.

The after-the-fact guarantees by banks of their sponsored conduits may have shaped the unfolding of the ABCP crisis and its consequences for investors. The bank-sponsored conduits appear to have suffered the same collapse of investor confidence as others and, without the support of their parents, would have faced the same liquidity squeeze. Had this happened, the crisis might have progressed differently. A larger proportion of conduits would have been unable to rollover their notes and the proportion could have been sufficient to have satisfied the condition of a general market disruption, triggering liquidity support that would have allowed the non-bank conduits to pay off their maturing notes. The conduits may still have failed, but the distribution of losses would have been quite different. More of the costs of the failures would have been borne by the liquidity providers, and less by the note holders.

The transfer of the banks’ ABCP activities from off- to on-the balance sheet established an unfortunate precedent to the degree it has led banks to believe that they can support off-balance sheet activities that run into trouble. If this is so, the distinction between off- and on-balance sheet would lose much of its significance, giving banks an incentive to keep as many activities off-balance sheet as possible. [29]