Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Creating an Advantage in Global Capital Markets

Structural Reform of Financial Regulation in Canada

A Research Study Prepared for the

Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Eric J. Pan

Structural Reform of Financial Regulation in Canada

Biography

Eric J. Pan

Eric J. Pan is Associate Professor of Law and Director of The Samuel and Ronnie Heyman Center on Corporate Governance at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in New York City. He is also an Associate Fellow in the International Economics Programme of the Royal Institute for International Affairs (Chatham House) in London and has been a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York and Washington, DC.

Prof. Pan conducts research on financial regulation, capital markets, corporate governance and international law. Among his many professional activities, Prof. Pan directs the London-based Chatham House City Series, serves as a member of the International Bar Association’s Securities Law Task Force on Extraterritorial Regulation and frequently speaks about international financial and corporate law issues across North America, Europe and Asia.

Before joining the Cardozo School of Law, Prof. Pan was an attorney for several years in the Washington, DC office of Covington & Burling, where he worked in Covington’s corporate, securities, and international practice groups. His practice consisted of mergers and acquisitions, public and private securities offerings, securities regulation, general corporate advisory work, and public and private international law matters. Before his time at Covington, he was a Jean Monnet Lecturer in Law at Warwick University, England, and served as director of Warwick’s Programme in Law and Business. He was also a visiting fellow at the Lauterpacht Centre for International Law at Cambridge University, England.

Prof. Pan received an A.B. magna cum laude in Economics from Harvard College, a M.Sc. with distinction in European and International Politics from Edinburgh University, Scotland, and a J.D. cum laude from Harvard Law School.

Executive Summary

Reform of its financial regulatory system affords Canada the opportunity to rethink not only how to better regulate its financial markets but also how to make its markets more attractive to financial market participants. In the current environment, where financial market participants are increasingly mobile, governments must be careful that achieving one objective is not at the expense of the other. Companies, investors, financial services firms and other financial market participants can now conduct business in a variety of locations around the world. Therefore, Canada, like all countries, can no longer take for granted the existence of a vibrant domestic financial market that will continue to meet the growing demands of Canadian businesses and households; rather it must consider how to attract financial activity to Canada in order to remain a leading global financial player.

The globalization of financial markets offers a compelling reason why Canada should pursue regulatory reform of its financial sector. In recent years, the United States, European Union and other jurisdictions have recognized that greater regulatory cooperation is needed to manage the cross-border markets. Many of Canada’s economic competitors have devoted a great deal of resources to consider how to converge and harmonize their regulatory standards and seek formal and informal means to cooperate on the development of new regulation. As a consequence, international standards and best practices are being negotiated and developed today that may govern international capital raising, securities and derivatives trading, and lending practices for decades into the future. To the extent that the structure of Canada’s financial regulatory system hinders Canada’s full participation in these international discussions, structural reform should be undertaken to give Canada a stronger and more consistent voice.

With these objectives in mind, Canada should adopt the following reforms. First, regulatory authority should shift to agencies operating under the auspices of the national government capable of representing national as well as local and provincial interests. Financial activity frequently extends across more than one province and can be more effectively overseen by a national regulator. In addition, the national government is in the best position to represent all of Canada’s interests in international forums and in negotiations with other jurisdictions. Second, the Canadian regulatory system should be restructured in accordance with objectives-based regulation. Individual regulators should be organized in accordance with one of three categories of financial regulation: (i) prudential regulation; (ii) business conduct regulation; and (iii) market stability measures. In pursuing objectives-based regulation, Canada should not let itself be trapped in a false choice between a “single regulator” model and a “twin peaks” model. What is most important is that Canada’s regulators have clear lines of authority, share information freely and continuously, and coordinate regulatory actions. Finally, structural reform should be accompanied by additional resources for supervision and enforcement to enable the introduction of supervisory approaches and principles-based regulation. Such a shift in regulatory resources will improve the attractiveness of the Canadian markets in the eyes of global financial institutions as well as enhance the effectiveness of the regulatory system in ensuring the markets’ safety and soundness.

Table of Contents

- I. Designing an Optimal Regulatory System

- II. Canada’s Regulatory System

- III. Comparative Analysis of the United Kingdom, Australia, United States, France, Germany, Netherlands and Hong Kong

- IV. Recommendations

- V. Conclusion

Structural Reform of Financial Regulation in Canada

Financial regulation has two goals: to ensure the safety and soundness of the financial system (which includes the promotion of consumer protection) and to foster the growth and development of the financial markets. In the current, global financial environment, where financial market participants are increasingly mobile, governments must be careful that achieving one objective is not at the expense of the other. Satisfaction of both goals will have great benefits for a country, including, among other things, lower cost of capital for businesses, greater opportunities for investors, tax revenue for the government and job creation in the financial and related industries.

Canada so far has avoided many of the economic problems that currently plague the United States and United Kingdom. Canadian financial institutions have not declared the large losses that have weakened, and in some cases crippled, US and UK financial institutions. At the same time, Canadian consumers do not appear to suffer from the same debt burden and crisis of confidence that currently weigh heavily on American and British households. Canada’s economic fundamentals are also more favorable than that of the United States and United Kingdom with Canada enjoying relatively low unemployment, a healthy trade surplus and budget surpluses. Given the difficult economic conditions in the United States and United Kingdom, it is not surprising that the recent US and UK debate about financial regulation and possible regulatory reforms has focused on how to respond to the current financial crisis and prevent future crises. [1] Canada, on the other hand, enjoys the luxury of thinking more long-term and should consider how regulatory reform can be used to make the Canadian financial markets more robust, innovative and attractive to global financial players.

Regulation’s role in making a country’s financial markets more competitive relative to other countries’ financial markets is of increased national concern. National financial markets are becoming increasingly interconnected and interchangeable. This globalization of financial markets manifests itself in the expansion of financial services now provided to Canadians by foreign financial services providers as well as the number of foreign customers now served by Canadian financial institutions. Many Canadian companies sell and list their securities on exchanges located outside of Canada and seek financing from foreign banks and investment funds, and prices for agricultural products, metals, oil and gas and other commodities that are so important to the Canadian economy are predominantly set by trading markets located outside of Canada. Companies, investors, financial services firms and other financial market participants can now conduct business in a variety of locations around the world. Therefore, Canada, like all countries, can no longer take for granted the existence of a vibrant domestic financial market that will continue to meet the growing demands of Canadian businesses and households; rather it must consider how to attract financial activity to Canada in order to remain a leading global financial player. [2]

The globalization of financial markets further offers a compelling reason why Canada should pursue regulatory reform of its financial sector. In recent years, the United States, European Union and other countries have recognized that greater regulatory cooperation is needed to manage the cross-border markets. Many of Canada’s economic competitors have devoted a great deal of resources to consider how to converge and harmonize their regulatory standards and seek informal and formal means to cooperate on the development of new regulation. In recent years, we have seen the wide-spread acceptance of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and eXtensible Business Reporting Language, negotiation of mutual recognition regimes for broker-dealers and exchanges, execution of bilateral and multilateral memoranda of understanding to facilitate information sharing, and new regulatory and standard-setting initiatives by international bodies such as the Bank for International Settlements, International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) and International Monetary Fund. These international developments directly affect Canadian companies, investors and financial services providers. International standards and best practices are being negotiated and developed today that may govern international capital raising, securities and derivatives trading, and lending practices for decades into the future. To the extent that the structure of Canada’s financial regulatory system hinders Canada’s full participation in these international discussions, structural reform should be undertaken to give Canada a stronger and more consistent voice.

With these objectives in mind, Canada should adopt the following reforms. First, regulatory authority should shift to agencies operating under the auspices of the national government. Financial activity frequently extends across more than one province and can be more effectively overseen by a national regulator. In addition, the national government is in the best position to represent all of Canada’s interests in international forums and in negotiations with other countries. Second, the Canadian regulatory system should be reorganized in accordance with objectives-based regulation. Individual regulators should be organized in accordance with one of three categories of financial regulation: (i) prudential regulation; (ii) business conduct regulation; and (iii) market stability measures. As discussed in this report, Canada should not let itself be trapped in a false choice between a “single regulator” model or “twin peaks” model. What is most important is that Canada’s regulators have clear lines of responsibility, share information freely and continuously and coordinate regulatory actions. Finally, structural reform should be accompanied by additional resources for supervision and enforcement to enable the introduction of supervisory approaches and principles-based regulation. No reorganization of Canada’s regulatory system will be successful without the retention of knowledgeable and dedicated regulatory professionals capable of working closely with financial institutions to ensure compliance with applicable rules and regulations. Such a shift in regulatory resources will improve the attractiveness of the Canadian markets in the eyes of global financial institutions.

This report is divided into four parts. Part One outlines the various issues that should be considered in designing the optimal regulatory system. The purpose of Part One is to set forth the basic concepts that are associated with the regulation of markets. It begins by reviewing the basic tasks that must be met by a regulatory system. It then discusses the ideal characteristics of such a system, including regulatory efficiency, accountability, competency and legitimacy. Part One also describes possible strategies that may be called upon by the regulatory system to achieve its objectives, outlining the pros and cons of regulatory competition and regulatory cooperation, and evaluates the relative merits of the single regulator and twin peaks models. Part Two of the report analyzes Canada’s current regulatory system in light of the criteria set forth in Part One. In order to position Canada’s system in relation to its main economic competitors, Part Three reviews the regulatory systems of the United Kingdom, Australia, United States, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan and Netherlands. In the case of the United States, the report discusses both the current US regulatory system and the system proposed by the US Treasury Department in its recent Blueprint for a Modernized Financial Regulatory Structure . [3] Finally, Part Four offers a series of recommendations for reforming the Canadian financial regulatory system. These recommendations draw upon the experience of other countries in effecting regulatory reform as well as a strategy to make the Canadian financial markets more attractive to financial market participants.

I. Designing an Optimal Regulatory System

The design of an optimal regulatory system should begin with an understanding of the objectives of the regulatory system, the ideal characteristics of such a system, the various regulatory strategies that might be applied to achieve those objectives, and, finally, the desired structure of the regulatory system.

A. Regulatory Objectives

The first objective of financial regulation is to ensure the safety and soundness of the financial system. Accomplishment of this goal consists of three tasks: prudential regulation, business conduct regulation and market stability protection. [4]

Prudential regulation refers to the range of regulations and regulatory acts applied to certain financial institutions – banks, securities firms and insurance companies – to ensure that they are financially sound and capable of meeting their market obligations. Regulators have a great interest in the health and operations of these financial institutions as the failure of one or more of these institutions could result in a loss in confidence in the safety and soundness of the financial system – causing a sharp contraction in financial activity and the weakening of other financial institutions – and the need for public intervention. Prudential regulation includes, among other things, capital adequacy rules, internal controls and record keeping requirements, risk assessments and mandatory professional qualifications for key personnel. Prudential regulation also can refer to the monitoring and inspection of financial institutions on an on-going basis by the regulator accompanied by sanctions and prosecution for violations or unsafe practices. The purpose of prudential regulation is to make sure a financial institution is not assuming risks that could endanger the financial health of the institution and its commitments to investors and depositors as well as to provide the regulator with sufficient information to identify potential problems before such problems become serious enough to result in a failure of the institution.

In contrast, business conduct regulation focuses on protecting customers that buy financial products or otherwise entrust funds to financial institutions. Business conduct regulation provides consumer protection by addressing the unequal position of financial institutions relative to their customers. The most vulnerable customers are retail clients who often lack the sophistication and information necessary to protect themselves from fraud, market abuse or ill-informed advice and must rely on financial institutions and the representatives of those financial institutions to protect their interests. [5] Consequently, regulators must address this information asymmetry by imposing requirements on financial institutions to disclose conflicts of interest, offer appropriate disclosures of risk, provide detailed and understandable information about investments and financial products and services, train their personnel to comprehend the needs of customers and clients in order to provide appropriate advice and assistance, and assume certain fiduciary obligations. Business conduct regulation also includes regulations that promote investor protection where regulators impose on securities issuers’ obligations to provide accurate material information on an on-going basis to investors.

Beyond the regulation of financial institutions and the protection of customers, regulators also must safeguard the overall stability of the market. Regulators must sustain the financial infrastructure necessary to keep the financial markets operating in a smooth manner. This task includes maintaining the payments system, providing short-term and overnight lending and managing the money supply. The responsibility to ensure market stability also refers to the need to intervene during times of crisis and fulfill the role of lender of last resort and liquidity provider when the failure of a financial institution might cause serious harm to the financial system. Market stability protection is different from other regulatory activities because the responses associated with the protection of market stability frequently require the government to enter the market as counterparty in financial market transactions. Market stability regulation is often the responsibility of the central bank, independent of any direct regulatory duties of the central bank. As recent events in the United States and United Kingdom have demonstrated, however, market stability operations that require government intervention as a lender of last resort, a source of liquidity or a guarantor of financial obligations is inextricably tied to the protection of customer assets and the soundness of financial institutions, justifying a role for the central bank in the regulatory process.

The other objective of financial regulation is to foster the growth and development of the financial markets. A regulatory system makes financial market growth possible by promoting innovation and permitting the development of new markets for financial services. A regulatory system is more likely to attract innovation and new market development if financial market participants perceive that regulators are responsive to their interests and that applicable regulatory standards and requirements are appropriate. As a result, lack of growth or innovation may be the result of regulation that imposes higher-than-necessary costs on market participants or limits the ability of financial service providers to enter into new lines of business. In the current global marketplace, an unattractive market will cause the movement of financial activity to other markets. Financial markets are in competition with each other, and regulatory reform should take into consideration the impact of the structure of the regulatory system on financial market activity.

It should be noted that some traditional scholars of financial regulation may disagree that one of the objectives of financial regulation is to promote financial market competitiveness. Such scholars believe that the only objective that regulators should be concerned with is the safety and soundness of the financial system, including the provision of consumer protection. But such a view ignores the realities of global financial markets today where the free movement of capital and financial services activities means that markets compete against one another and that regulators can no longer promulgate and implement new regulation without considering the costs of such regulation on financial market participants. [6]

B. Characteristics of an Optimal Regulatory System

In designing the optimal regulatory system to achieve the objectives described above, the system should have four basic characteristics: efficiency, accountability, competency and legitimacy. These four characteristics underpin a regulatory system’s effectiveness in meeting its objectives. First, the organization and operation of regulators should seek to provide optimal regulation in the most efficient means possible. The structure of the regulatory system should be designed to avoid redundancy where different parts of the regulatory system have overlapping responsibility over a particular financial activity or entity. One of the problems with the current US system is that financial institutions, especially banks, find themselves regulated by more than one regulatory agency at both federal and state levels. US financial institutions complain of higher compliance costs and inconsistent regulation and enforcement by competing regulators. From the government’s perspective, having more than one agency regulate the same matter is an inefficient deployment of regulatory resources. To address this problem, regulators should have clear lines of authority, eliminating unnecessary duplication. To the extent that several agencies have an interest in a single regulatory matter, one agency should have the lead in managing the problem with clear procedures for consulting with other interested agencies. Likewise, information processing and support operations should be shared by all regulators to eliminate overhead, and financial institutions should not have to report identical information to different agencies.

Second, the regulatory system should be designed to promote accountability. With respect to any regulatory matter, it should be clear which regulator is responsible for addressing the matter. Consequently, a financial institution should know where to direct inquiries or to whom they should raise concerns, and members of the public and elected officials should know, and hold responsible, that regulator for any regulatory failures. In the United States, there has been extensive criticism of the failure of any regulatory agency to prevent or respond to the collapse of the subprime mortgage market. In reality, various agencies had partial responsibility for different aspects of the market. [7] The inability to identify which agency was responsible for this sector of the financial market is one reason for the dissatisfaction felt about the current structure of the US financial regulatory system.

Likewise, the regulatory system needs to promote international accountability. Foreign regulators should know whom to call if there is an issue that requires international coordination. One of the difficulties that plagued the early development of the European financial markets was the lack of a regulatory authority in the European Union that could speak for the European Union in matters requiring consultation with the United States and other major economic powers. [8] International accountability also means that one regulator should be authorized to represent the country’s interests in international forums. The need to identify an agency that is accountable suggests consolidating disparate regulatory bodies or at least establishing a hierarchy of regulators.

Third, the regulatory system should be designed to promote competency. It goes without saying that regulators should be competent, but the manner in which the regulatory system is structured can further improve the competency of regulators by ensuring that those regulators with applicable skills and expertise are assigned to accomplish certain regulatory tasks. Competency consists of a variety of elements. Among them is expertise. A priority of the regulatory system should be to recruit and retain individuals who are knowledgeable about the financial sector and the activities that they are regulating. Also, the regulatory system should endeavor to assign regulatory responsibility to that part of the regulatory system that is in the best position to collect the necessary information and to respond to issues of regulatory concern. One (but not the only) justification for the delegation of regulatory authority to self-regulatory organizations (SROs) is that financial market participants that make up SROs are in a better position than a government regulator to understand market developments and to identify and resolve potential problems.

Another element is experience. Regulators should work on regulatory problems with which they have experience. This observation is an argument for reorganizing regulators along the lines of regulatory objectives (referred to herein as objectives-based regulation) as opposed to merely by financial sector or activity. For example, it would not be desirable to have a regulator with experience in prudential regulation to also oversee business conduct rules.

Competency is also a function of culture and experience. Regulatory agencies – like all organizations – develop internal processes and practices over the course of time that govern how they approach regulatory tasks and apply past lessons to current problems. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), for example, has a long and distinguished history of being an effective and respected regulator of the US markets. [9] To the extent possible, structural reform of the regulatory system should keep existing, successful agencies intact, preserving institutional knowledge and practices.

Fourth, the regulatory system should be legitimate. Legitimacy is the ability of agencies to have their regulations recognized and accepted by market participants. While regulatory agencies may have legitimacy by virtue of their legal authority, regulatory agencies are more effective when their actions and decisions are viewed as substantively correct by market participants, producing confidence in the competence of the regulators.

Three factors that can help a regulatory system earn and retain legitimacy are independence from political interests, accountability to public and market opinion, and transparency. The credibility of regulatory agencies is undermined if their actions are viewed as being influenced by political interests (i.e., that regulatory actions favor certain political constituencies or are the result by current political trends rather than by sound principles of financial regulation). One example of where political influence undermined regulatory legitimacy is Japan’s response to its financial difficulties in the 1990s. Until Japan reformed its regulatory system, the Japanese Ministry of Finance played an unusually active role in regulating Japan’s troubled banks. [10] Many commentators attributed Japan’s slow recovery to the Ministry of Finance’s unwillingness to pressure the banks to declare their losses quickly and restructure themselves. Instead, the Ministry of Finance tried to prevent political backlash by helping the banks hide the true extent of the losses. It took several years before investor confidence in the Japanese financial markets returned to normal.

At the same time, however, regulators cannot be entirely independent of political pressure because their legitimacy also stems from their accountability to the public. One concern about the creation of a single super-regulator in the United States is that such an agency would be too powerful to control by the US Congress. Such a concern resonates with commentators in the United States because US regulatory agencies have a great deal of day-to-day autonomy from Congress and the President. But such concerns can be addressed if the legislature and executive retain the power to set the priorities of the regulators, have the power to remove and appoint the heads of regulatory agencies, and are briefed and consulted frequently by the regulatory staff. Regulators, on the other hand, must have the freedom to act without political interference and retain the ability to interpret their statutory objectives in developing relevant rules and regulations.

Finally, regulators must be transparent in how they develop their rules and regulations and conduct enforcement actions. Such transparency can be achieved by holding public meetings, providing notice and comment on new rules and regulations, allowing regulated entities to consult with – and seek guidance from – regulators on an on-going basis, and disclosing other relevant information about internal deliberations and policy interpretations. It should be noted that central banks tend not to be transparent which causes concern about their role as financial regulators. Together, legitimacy along with efficiency, accountability and competency are essential components of a successful financial regulatory system

C. Regulatory Strategies

The most challenging task for regulators is to strike the proper balance between the twin objectives of ensuring the safety and soundness of the financial system and improving the attractiveness of the market to provide the conditions for the growth and development of the financial markets. Under-regulation, which can mean either the absence of regulatory action or the under-enforcement of existing regulations, may leave the financial system susceptible to systemic failure, fraud or loss of confidence by market participants. But over-regulation may prevent financial institutions from doing business in a cost-effective manner and drive financial activity to other, more favorably regulated markets.

In order to find this right balance of regulation, regulators can look to employ three basic strategies: regulatory competition, regulatory cooperation and self-regulation. Regulatory competition is when regulatory regimes are set up as alternatives to one another. Those institutions and persons subject to regulation are allowed to move from one regime to another, choosing their preferred regulatory regime. In other words, market participants face a menu of regulatory choices, allowing them to select the set of regulations that best fits their needs. Customers and investors will participate only in those markets which have sufficient regulatory protections. At the same time, financial service providers and corporate issuers will only participate in those markets where the burden of regulatory compliance is reasonable. Regulatory competition addresses the problem of finding the right balance by allowing market participants – investors and customers, on the one hand, and financial firms and issuers on the other – the ability to select the regime that best meets their needs. The regime that attracts the most number of market participants and hosts the greatest level of financial activity is the one that offers the optimal level of regulation. In turn, regulatory competition assumes that regulators will modify and tweak their regulations to become more attractive to both sets of market participants. As a result, regulatory competition empowers the financial markets to identify the most suitable regulatory regime.

One concern frequently raised in connection with regulatory competition is the danger of a “race to the bottom” where the desire to attract financial service providers and corporate issuers (via deregulation) overwhelms the need to maintain adequate regulatory standards to ensure the safety and soundness of the financial system. The race to the bottom description, however, exaggerates the risk that regulators will abdicate their regulatory responsibility in order to attract new business to their markets. Regulators also have a powerful incentive to impose additional regulation in order to make their markets more attractive to retail and institutional customers and investors. A race to the bottom is often more accurately a race to the middle.

Regulatory competition is an attractive regulatory strategy because it assumes that competitive pressure – pressure that will force regulators to improve repeatedly their regulatory systems – will result in the discovery of the optimal regulatory regime. Regulatory competition also may be a superior regulatory strategy if several optimal regulatory regimes exist for market participants with different characteristics. For example, sophisticated institutional investors may elect to invest in markets that have weaker investor protections because they feel more capable of protecting themselves in such a regime while retail customers and investors may prefer heavier regulated markets that emphasize stricter disclosure requirements and more investor protections.

One essential ingredient for regulatory competition is a “passport” system where firms that satisfy the requirements of one regulatory regime are given unfettered access to all other markets. Such a passport system has been attempted by other countries, most notably the European Union, with limited success. [11] Without a passport, regulated firms cannot move to the regime that offers a preferable set of regulatory requirements.

Regulatory competition, however, may not be an appropriate strategy if regulators have reason to believe that market participants do not have complete information or the skill to evaluate the appropriateness of different regulatory regimes, that regulators do not have sufficient resources or incentives to compete against one another, or that there are minimum regulatory standards that should be provided by all regulatory regimes regardless of their perceived value to market participants. As a result, an alternative regulatory strategy is regulatory cooperation. Regulatory cooperation is when regulators from different regimes look to converge and harmonize their regulations, causing the different jurisdictions to share approximately the same regulatory standards. Such convergence and harmonization eliminate the opportunity for market participants to evade these standards by moving to a different regulatory regime.

Regulatory cooperation assumes that the regulators know the appropriate level of regulation for the market and that all market participants must abide by the same regulations in every jurisdiction. While there is a risk that the standards set by the regulators may be too high, regulatory cooperation may produce cost savings by eliminating the need for market participants to evaluate the differences between competing regimes and other regulatory costs associated with individual regulatory agencies trying to stay competitive with each other.

The main challenge associated with regulatory cooperation is the process by which such cooperation takes place. In the case of the European Union, the European Commission attempted to impose a common set of regulatory standards on the individual member states through a series of directives. [12] The initial directives proved unsuccessful as some member states resisted the European Commission’s efforts and refused to implement the directives in a full and consistent manner. More recent efforts by the European Commission to establish a common set of standards have proven more successful because the European Commission accompanied the new directives with, among other things, the establishment of the Committee of European Securities Regulators to provide a forum for regulatory cooperation and to ensure proper implementation of the directives. The EU experience offers a model for regulatory cooperation at both the national and international levels.

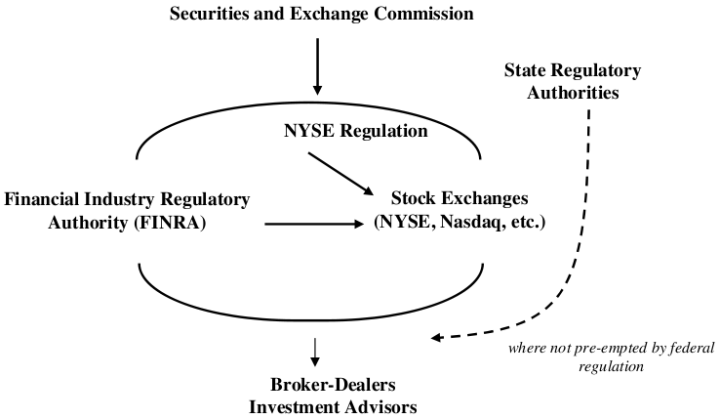

In the case of self-regulation, regulators delegate responsibility for standards-setting and rule-making to representatives of the market. The rational behind self-regulation is that market participants, by virtue of having better information and knowledge of market events, are in a superior position to determine the appropriate level and scope of regulation. SROs also may be able to respond more quickly and in a more flexible manner to market developments. Self-regulation is often considered less expensive (from the perspective of the government) than direct regulation as the financial industry is charged with paying for its own regulatory apparatus.

A prominent example of self-regulation is the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) in the United States and its predecessor, the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD). [13] FINRA is the primary regulator of securities firms in the United States. It oversees nearly 5,000 brokerage firms and over 676,000 securities professionals. [14] As a self-regulatory organization, FINRA receives its authority from the SEC and is funded by its members. When the SEC recognized the first SROs, the then SEC Chairman William O. Douglas described the role of the SEC as being like a “shotgun, so to speak, behind the door.” [15] The SEC would oversee the SROs, but would only intervene if it determined that the SROs were failing to carry out their respective regulatory missions. Over the course of the past 60 years, the SEC has intervened several times to tighten the regulation of the securities firms and has taken an active role in reviewing the regulatory actions of FINRA (and previously the NASD). [16] Nonetheless, the self-regulatory model offers a powerful means to give market participants an influential role in determining the appropriate level and form of regulation.

In restructuring the Canadian regulatory system, policymakers should consider how to utilize all three of these regulatory strategies in both its domestic and international affairs. Regulatory competition, for example, may be useful in considering whether to continue to allow for diversity of regulation among the provinces and to effect a full passport system to generate competitive pressures on the provinces. Regulatory cooperation, on the other hand, is helpful in understanding how Canada can go about developing a single set of regulations for the entire Canadian market. It also anticipates the task that lays ahead in converging Canadian regulation with those of other major financial market jurisdictions, most notably the United States and European Union. Finally, self-regulation supports the argument that some financial activities should not be directly regulated by any regulatory agency but rather left in the hands of market participants.

D. Organization of Regulatory System

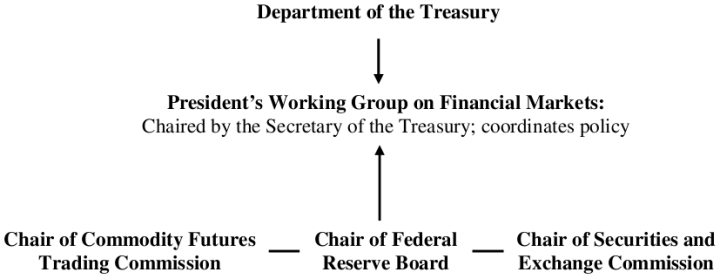

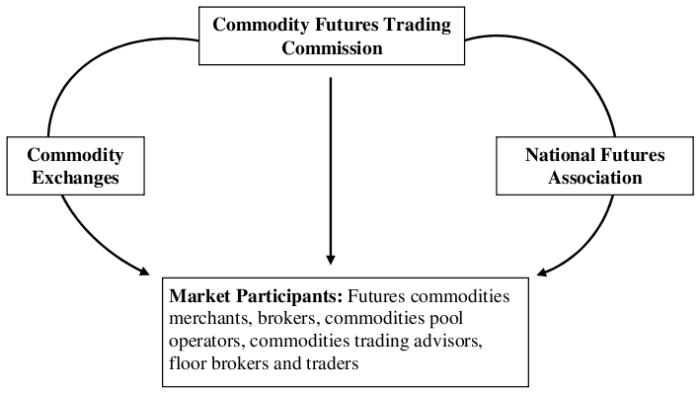

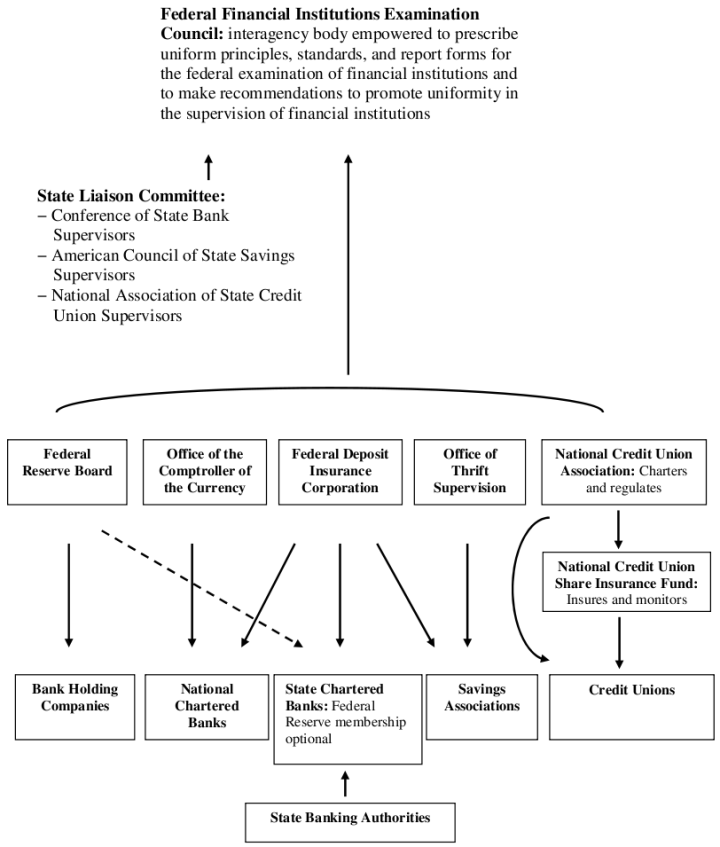

The final consideration behind designing the optimal regulatory system is its organization. An examination of the regulatory systems adopted by many of Canada’s main economic competitors (as described in Part Three of this report) reveals a diverse range of organizational forms. The United States, for example, has a multitude of federal and state regulators that separately regulate securities firms, banks and insurance companies (see Appendix B). Three federal regulators alone oversee US banks (with a fourth focused on credit unions). In the United Kingdom, almost all regulatory responsibility is in the hands of its Financial Services Authority (UK FSA). Australia and The Netherlands divide regulatory responsibility between two large regulators. Other countries organize their regulatory structures to fall in between the single regulator and “alphabet soup” models.

In determining the best way to organize Canada’s regulatory system, three questions must be answered. First, how should regulatory responsibility be divided among regulators? One possibility is to have regulatory authority divided by financial sector. The United States offers one example of sector-based regulation, especially in the banking area, where the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency regulates national chartered banks, state banking authorities regulate state chartered banks, the Office of Thrift Supervision regulates saving and loans associations, and the National Credit Union Association supervises credit unions. The advantage of sector-based regulation is that each agency develops a deep expertise in its particular sector, giving it a better understanding of regulated firms’ activities and practices. On the other hand, sector-based regulation is inherently inefficient. Each regulator cares only for its small part of the financial system and is not in a strong position to identify and respond to systemic threats arising from other sectors in the financial system. It is also likely that such a system would produce frequent duplication of regulatory efforts. When a regulatory problem affects multiple sectors of the financial system, several agencies ultimately respond to the same problem – often in different ways and with different degrees of success. Sector-based regulation is especially ill-suited to regulate financial conglomerates that provide services across financial sectors. As many large financial institutions now provide banking, securities and insurance services, they find themselves subject to oversight by multiple regulators with no single regulator having responsibility for examining the overall health of the institution. Thus, sector-based regulation raises significant concerns that regulators are not providing appropriate protection for markets where sectoral divisions are increasingly irrelevant.

An alternative way to organize regulators (but still quite similar to the sector-based system described above) is having separate regulators focus on the type of financial activity. For example, there could be one regulator responsible for overseeing all deposit and lending activities, another responsible for the sale of insurance, a third responsible for securities issuance and trading, a fourth responsible for futures trading and a fifth regulating investment management services. Activity-based regulation, however, still suffers from the same basic flaw as sector-based regulation: it does not fully address the challenge of having individual financial institutions be subject to oversight by multiple regulators. Consequently, no single regulator has all of the necessary information and authority (and, arguably, the incentive) necessary to monitor the overall health of the financial institution and the impact that such financial institution may have on the overall safety, soundness and stability of the financial system.

A third option, and the one recommended in the recent US Treasury Blueprint, is to adopt an objectives-based approach. In contrast to the sector-based and activity-based approaches, the objectives-based approach recommends arranging regulators in accordance with the three tasks necessary to ensure the soundness and safety of the financial system: one regulator is responsible for prudential regulation, a second regulator responsible for business conduct regulation and a third regulator responsible for market stability measures. The advantage of the objectives-based approach is that regulators retain a certain degree of specialization (if one assumes that all prudential regulation, business conduct regulation and market stability responses are the same regardless of financial sector or activity), while each regulator has a “bigger picture” view of the financial system by virtue of regulating firms that operate across sectors. This bigger picture view increases the chance that regulators will be able to prevent systemic crises. The objectives-based approach appears best suited for the modern financial system where financial firms no longer neatly fall into the traditional categories of banking, securities and insurance.

The different approaches affect the number of regulators needed to oversee the regulatory system. The sector-based and activity-based approaches require more regulators than the objectives-based approach because the focus of each regulator is narrower. Even in the case of the objectives-based approach, there is a question as to whether regulatory authority should be concentrated in the hands of a single regulator (the single regulator model), two regulators focused respectively on prudential regulation and business conduct regulation plus a market stability agency (the twin peaks model) or multiple regulators with one regulator responsible for managing the other regulators (the lead regulator model).

The single regulator model is attractive because of its simple organizational form. The single regulator does not have to share or coordinate actions with another regulator, eliminating any possibility that issues of concerns will fall between the jurisdictional cracks of separate regulators or be the subject of “turf battles” between agencies. There are economies of scale associated with having a single, large regulator handle all regulatory issues rather than having separate regulators work independently. Proponents of the single regulator model note that the United Kingdom’s move to a single regulator in 1998 resulted in cost savings at least in the first four years of its existence. [17] A single regulator also is better equipped to oversee more complex financial institutions and financial products since it has undisputed regulatory authority over all aspects of the financial market. Furthermore, the single regulator model provides ultimate accountability since all queries and concerns are automatically laid at its doorstep.

The single regulator model, however, assumes that a single agency can meet all regulatory objectives simultaneously and in a satisfactory manner. This is easier said than done. The single regulator model shifts the decision of setting regulatory priorities and allocating regulatory resources from an external debate (i.e., the support of various regulatory agencies through the public budget) to an internal debate where the managers of the single regulator decide on regulatory priorities and allocate resources accordingly (often outside of public scrutiny). Such a shift poses several risks. One risk is that certain regulatory objectives are pursued at the expense of others, creating areas of under-regulation. Another risk is that the regulatory system moves from being one of many groups of specialists, with intense expertise in their respective areas of regulatory authority, to a single group of generalists. The concern is that sector-specific knowledge and expertise is lost, undermining the efficiency gains of having a single regulator overseeing all sectors of the market. A third risk is that the lack of clear lines of responsibility within the single regulator could lead to confusion, especially if the single regulator is attempting to integrate previously independent, and single-minded, regulatory agencies. It is unclear whether a single regulator that is assuming the responsibilities of several former regulatory agencies will be able to organize itself in a more effective manner to eliminate the turf battles and blind spots associated with the older regulatory system.

The twin peaks model also attempts to achieve many of the same benefits as the single regulator model – eliminate regulatory redundancy, reduce overhead and provide clearer lines of responsibility and authority for regulators. The twin peaks model, however, rejects the premise of the single regulator model that all regulatory authority can be combined in one body. Instead, the twin peaks model is based on the belief that there is a fundamental difference between the objectives of prudential regulation and those of business conduct regulation – a difference that requires prudential and business conduct regulators to invoke different strategies and approaches. In the case of prudential regulation, the regulator assumes a more cooperative relationship with the financial institution. The regulator exists to assist financial institutions. Its role is to set standards and monitor the maintenance of those standards by the financial institution. To the extent a financial institution fails to meet certain standards or the regulator identifies a possible threat to the soundness of the financial institution, the role of the regulator is to work with the financial institution and find a solution. In contrast, a business conduct regulator is frequently in an adversarial position relative to the financial institution. This regulator is effectively a representative of the customers and investors, using its rulemaking powers to impose new requirements on financial institutions and its enforcement powers to discipline and punish financial institutions for business conduct violations. A concern with giving a single regulator responsibility for both prudential and business conduct regulation is that such a regulator would not apply the appropriate regulatory approach to each task. A single regulator may favor the stronger enforcement approach more suitable for business conduct regulation and apply such approach to prudential regulation, establishing an undesirable adversarial relationship where financial institutions avoid raising problems with the regulator for fear of prosecution. Such a result where financial institutions refuse to open themselves up to the regulator would undermine that regulator’s ability to monitor and identify sources of systemic risk. Or, alternatively, the more cooperative approach that one would expect in matters of prudential regulation is applied to business conduct regulation to the detriment of unwitting customers and investors. The twin peaks model attempts to resolve this conflict by keeping separate prudential and business conduct regulation.

One of the weaknesses of the twin peaks model is the need for coordination between the two agencies. The potential for conflict is greatest when the two agencies representing the respective peaks are regulating the same financial firm – an occurrence that is quite common (consider, for example, the regulation of insurance companies which must satisfy prudential regulatory standards as well as business conduct rules in its dealings with policyholders). As large financial firms continue to expand their activities across the banking, securities and insurance lines, one would expect the application of both prudential regulation and business conduct regulation to be the norm, and the regulatory actions of one will affect the other. One can easily imagine how aggressive enforcement of such entities by the business conduct regulator could undermine the financial stability of the firm, requiring a response of the prudential regulator. Therefore, the twin peaks model must be accompanied by some mechanism of coordination to resolve conflict that may arise between the two regulatory agencies. It is tempting to give responsibility for resolving all inter-agency conflict to elected government officials, but such an approach threatens to politicize the regulatory process.

A third alternative to the single regulator and twin peaks models is the lead regulator model. This model requires the least amount of reorganization of the current regulatory system. Separate regulatory agencies, and their lines of authority, are maintained. The one change is that a single agency is designated the “lead regulator” and assumes responsibility for coordinating the regulatory actions of the other agencies. This model is appealing because it builds upon the regulatory experience and expertise of sector- and activity-based regulatory systems while giving the impression that there will be at least one regulator who is looking at the overall picture.

The lead regulator model, however, raises a number of concerns. First and foremost, which agency should be made the lead regulator? Selecting one agency as the lead assumes that this agency has the expertise and competency to evaluate not only its own regulatory interests but also the interests of the other agencies that are now reporting to it. It also assumes that the lead agency will not be inherently predisposed to prioritize its regulatory interests above all others. If these assumptions are wrong, then the lead regulator model will likely produce even greater risk of regulatory failure as the lead regulator has more opportunity to ignore the concerns of its subordinate agencies. The second concern is that even if a suitable lead agency is identified, how will this agency manage the other agencies? Just as in the case of the twin peaks model, the lead regulator model will require some mechanism of coordination to resolve conflict, promote the sharing of information between agencies, and enable the lead regulator to direct action from the other agencies as necessary. Such a system would be quite complex, which raises a third concern. The lead regulator model is the least efficient of the three models. The lead regulator model continues to promote divided regulatory agencies with overlapping competencies and separate overhead. This system seems to have few advantages over those of the single regulator and twin peaks models.

The exact organization of the regulatory system is less important than the means by which regulatory agencies and internal regulatory divisions are made to work together and act in a coordinated fashion. With respect to each structure, coordination is vital whether the coordination takes place internally (as in the case of the single regulator model) or externally (as in the case of the twin peaks and lead regulator models). With that said, the single regulator and twin peaks models are superior to the lead regulator model because they more effectively eliminate overlap between regulatory agencies and enhance efficiency. Therefore, this report recommends that Canada adopts either the single regulator or twin peaks model.

II. Canada’s Regulatory System

A. Current Structure of Canada’s Regulatory System

In Canada, separate regulatory agencies regulate banking, insurance, securities and credit unions with the Bank of Canada in charge of monetary policy and market stability. Regulatory responsibility is also split between the national and provincial governments. The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC) share the responsibility for the regulation of banks. The OSFI supervises all federally-chartered depository institutions and insurance companies in Canada. While seventy percent of Canada’s securities dealers are owned by the country’s banks, the OSFI has limited, indirect authority over these dealers. In all of the provinces, except Ontario, OSFI oversight extends only to federally-chartered banks and not their subsidiaries, and, direct supervision of securities dealers is handled by the provincial authorities. In Ontario, the OSFI and the FCAC have a greater role in regulating certain securities activities pursuant to the Hockin-Kwinter Accord of 1987 between the national government and Ontario. The FCAC provides Canadian consumers with information about financial products and services and monitors the compliance of federally incorporated financial institutions with consumer protection laws. The FCAC is also the primary regulator of bank conduct in Canada. The OSFI and FCAC divide their regulatory responsibilities along the lines of prudential regulation (i.e., OSFI) and business conduct regulation (i.e., FCAC).

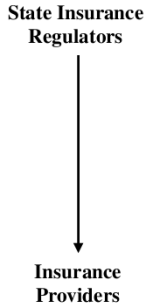

Regulation of insurance companies is divided between the national and provincial governments. The vast majority of insurance companies in Canada are subject to regulation by the OSFI and, to a limited extent, the FCAC. [18] While the provinces retain the authority to engage in prudential supervision of insurance companies operating within their borders, several provinces contract this function to the OSFI. [19] Business conduct regulation of all insurance companies in Canada, including those that are subject to prudential supervision by the federal agencies, is performed by the provincial governments.

While regulation of banks and most prudential regulation of the insurance industry take place primarily at the national level, the provinces have the lead role in regulating the securities industry and credit unions. Credit unions and caisses populaires are incorporated under provincial law, and the provinces set the applicable regulation. Outside of Quebec, the national government does play a limited role regulating the credit union industry as the Credit Union Central of Canada is chartered and regulated at the federal level. In addition, the central credit unions that serve British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia have elected to register under federal legislation in addition to being regulated at the provincial level.

Securities regulation is entirely in the hands of the provinces. Each province maintains its own securities commission. Four of these provincial commissions — Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec — participate in IOSCO, although only Ontario and Quebec are voting members. Canada is the only major country that is not represented in IOSCO by its national government. In order to promote coordination of regulation across borders, the provincial commissions have formed the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA), consisting of the chairs of the thirteen provincial securities regulators. The CSA’s goal is to “harmonize and strengthen securities regulation in Canada through enhanced inter-provincial cooperation.” [20] Towards this end, the CSA adopts national instruments designed to coordinate and harmonize changes to existing provincial laws. The impact of these instruments is limited, however, as the provincial regulators are under no obligation to enact them. The CSA has launched recently several initiatives to improve the functioning of securities regulation across Canada, including a Mutual Reliance Review System, System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval, National Registration Database and System for Electronic Disclosure by Insiders. Despite these successes, the provincial securities regulators still operate relatively autonomously of each other.

In recent years, the provinces have made significant efforts to improve coordination of regulation and reduce the regulatory barriers that divide the country’s securities markets. All of the provinces, with the exception of Ontario, participate in the Council of Ministers of Securities Regulation. One of the Council’s most important initiatives is the passport system to allow market participants from each province to operate freely in other provinces. The Council has delegated the job of developing the passport system to the CSA.

The passport system is being implemented in two phases. The first phase took effect in September 2005. Pursuant this phase, a market participant that obtains approval from its home provincial regulator (such regulator being that firm’s principal regulator) has the ability in limited cases to operate in other provinces without the need for further regulatory approvals. The implementation of a more comprehensive second phase of the passport system began in March 2008 and should be completed by mid-2009. Pursuant to this second phase, a market participant will be permitted to seek approval for its prospectus, register as a dealer or adviser or obtain regulatory exemptions from its principal regulator and in each case have such regulatory action recognized and honored by all other provinces.

Ontario has chosen not to participate in the passport system. Instead, the other provinces have agreed to unilaterally recognize Ontario such that the decisions of the Ontario Securities Commission concerning Ontario-based market participants will be accepted by the other provincial regulators. The Ontario Securities Commission, on the other hand, is under no obligation to recognize the decisions of the other provincial regulators.

In addition to the provincial commissions, several SROs play an important role in the regulation of Canada’s securities markets. The most important of these are the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) and Mutual Fund Dealers Association (MFDA). The IIROC, formed in 2008 by the merger of the Investment Dealers Association of Canada and Market Regulation Services, regulates the conduct of all investment dealers in Canada and enforces the trading and market integrity rules for the Toronto Stock Exchange, TSX Venture Exchange, Liquidnet Canada and other major trading markets and platforms. IIROC shares many similarities with FINRA in the United States described above. The MFDA, which commenced operation in 2001, regulates the sale of mutual funds in Canada.

Finally, the Bank of Canada plays an important role as the lender of last resort, supplier of emergency liquidity for eligible institutions, fiscal agent of the Canadian government and issuer of currency. It also has oversight responsibilities over systemically important payment systems. Unlike the Federal Reserve in the United States, however, the Bank of Canada does not supervise banks. In this respect, the Bank of Canada is more comparable to the Bank of England.

At the national level, two coordinating committees report directly to the Minister of Finance: Financial Institutions Supervisory Committee (FISC) and Senior Advisory Committee (SAC). Both organizations are comprised of the Superintendent of the OSFI, Governor of the Bank of Canada, Chair of the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation, Commissioner of the FCAC, and Deputy Minister of Finance. The FISC, which is chaired by the Superintendent of the OSFI, meets quarterly, but can be convened as needed, under a statutory mandate to review the health of regulated financial institutions and reports to the Minister of Finance. The SAC, which is not a legislated committee, meets as needed to review financial sector policy issues, including the existing legislative and regulatory environment. This group is chaired by the Deputy Minister of Finance.

B. Comments on Canada’s Regulatory System

Canada has the framework for an objectives-based system, as defined in this paper. In the area of banking and insurance, the division of responsibility between OSFI and FCAC follows the basic template of one regulator focused on prudential regulation and another regulator focused on business conduct regulation. Canada can build upon these two agencies to apply the objectives-based approach to all areas of its financial system.

The weaknesses of the Canadian regulatory system lie in the fact that parts of Canada’s regulatory system are still segmented by type of financial activity and regulation is split between the provinces and the national government. Ideally, Canada should strive to consolidate all of its regulatory activities in fewer agencies and, to the extent possible, consider giving primary regulatory responsibility for the securities markets to a national regulator.

Institutionally, FISC and SAC serve an important role as high-level coordinators of policy and regulation in the area of prudential regulation and market stability. It is unclear, however, what permanent arrangements exist among the other national regulatory agencies and between the national regulators and the provincial regulators to coordinate “lower-level” regulation, share information and cooperate on enforcement actions. The absence of the provincial regulators in the FISC and SAC is especially striking since it appears that the provincial securities regulators operate independently of OSFI and FCAC. To remedy this weakness, Canada should strengthen the cooperative links between the different regulatory agencies and consider the possibility of supporting the CSA to become an agency with power to take the lead on securities regulatory matters with legal powers over the provincial securities regulators.

To the extent securities regulation remains in the hands of the provinces, the passport system is an important development, albeit, as discussed later in this report, a second-best solution to a national securities regulator. As the experience of the European Union has shown, the implementation of a regulatory passport system naturally leads to enhanced regulatory coordination, regulatory convergence and the development of common regulations. [21] Over time an expansive application of the passport may eliminate most significant regulatory differences between the provinces. But such a strategy will take time and may not unfold smoothly. The passport remains a product of inter-provincial negotiation and, therefore, reliant on the continuing desire of the provinces to cooperate with one another and implement faithfully the terms of the passport. The fact that the passport does not fully incorporate Ontario and the first phase of the passport was hampered by the absence of harmonized legislation among the participating provinces [22] illustrates some of the challenges to, and weaknesses of, the passport system. Furthermore, the passport system does not ask any one provincial regulator to look beyond local interests and consider the development of a national securities market, nor does it empower any agency to initiate regulatory action necessary to strengthen the national markets without first obtaining the consent of all other regulators. Consequently, cooperation among provincial regulators based upon the passport system does not offer a very efficient and nimble regulatory structure for a leading financial market.

III. Comparative Analysis of the United Kingdom, Australia, United States, France, Germany, Netherlands and Hong Kong

In recent years, several countries have considered the problem of how to restructure their financial regulatory system. The reasons why each country decided to effect these reforms varies by jurisdiction. In the case of the United Kingdom, the new Labour government pursued regulatory reform in response to growing dissatisfaction with the United Kingdom’s then-current regulatory system’s ability to supervise new financial conglomerates and provide appropriate protection to consumers and investors attracted to exotic financial products. The introduction of the Euro and the establishment of the European Central Bank spurred France, Germany and The Netherlands to examine anew the role of their national central banks and financial regulatory systems. Hong Kong twice made structural reforms to its regulatory system after sharp downturns in the stock market. The United States began a high-profile study of its regulatory system in 2007 in order to address concerns that US regulation was harming the competitiveness of the US financial markets. More recently, reform efforts, as set forth by the US Treasury Blueprint published at the end of March 2008, are being directed to fix perceived regulatory failures behind the credit crisis in the United States. Despite the fact, however, that all of these countries have studied the problem of how to design an optimal regulatory system, they have disagreed as to the right answer. Instead, most of them have adopted, or are seeking to adopt, variations on two different models of regulatory systems – the single regulator model and the twin peaks model – but in several cases have fallen short of implementing all necessary reforms to garner the full benefits of either model.

A. United Kingdom

The United Kingdom follows the single regulator model, concentrating regulatory authority in the UK FSA. The creation of the UK FSA coincided with tremendous growth of London relative to other financial centers (including New York), leading some commentators to conclude that the United Kingdom’s version of single regulator model has proven itself superior to other regulatory systems.

Until 1997, the UK financial markets were subject to oversight by a variety of regulatory agencies and SROs. The Bank of England was responsible for regulating banks. The Securities Investment Board (SIB), London Stock Exchange (in its role as Listing Authority), Securities and Futures Authority, Investment Managers’ Regulatory Organization and Personal Investment Authority each had a role in regulating securities offerings and investment firms. The Insurance Brokers Registration Council regulated insurance companies. This panoply of agencies and SROs in the United Kingdom faced extinction in May 1997 shortly after the Labour Party under Tony Blair won the general election. Nineteen days into the term of the new government, then-Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown announced the consolidation of all banking, securities and insurance regulatory activities – the responsibility of nine different regulatory bodies – into the UK FSA.

Three observations can be made of the UK FSA. First, the decision by the United Kingdom to adopt the single regulator model was a great surprise. Before the general election, the Labour Party announced its intention to make only modest changes to the UK regulatory system. These pre-election proposals consisted mainly of recommending the shift of regulatory responsibility away from SROs to government agencies. The Chancellor of the Exchequer’s announcement of the creation of the UK FSA on May 20, 1997 was the very first indication that the Labour Party favored a single regulator. Given the lack of public discussion preceding the announcement, it is unclear why the government decided that a single regulator was essential or even necessary. Some commentators suggest that the decision to concentrate authority in the hands of the UK FSA was to satisfy the parliamentary timetable rather than the result of reasoned deliberation by the government of the great merits of the single regulator model. [23] The best substantive justification for the single regulator model was offered by the Chancellor in his proposing statement that the organization of the regulatory system must be reformed to reflect the fact that the distinctions between banks, securities firms and insurance companies had broken down. [24] The same justification, however, can also be used to advocate the twin peaks model, but there is no indication that the Chancellor considered this possibility. Strangely, the political origin of the UK FSA is rarely recalled by those who consider the UK FSA as strong evidence of the superiority of the single regulator model. Rather, a more skeptical commentator might conclude that the UK FSA’s success was more due to good fortune than to design.

Second, while the UK FSA is the dominant financial regulator in the United Kingdom, it shares responsibility for overseeing the financial system with the Bank of England and HM Treasury. UK FSA, Bank of England and HM Treasury documented their respective responsibilities in a memorandum of understanding. [25] The Bank of England is responsible for maintaining market stability. In other words, the Bank of England is responsible for seeing that the financial system functions smoothly in settling financial transactions, providing liquid markets for the exchange of financial instruments, and intermediating between savers and borrowers. At the same time, HM Treasury is the main instrument of financial and economic policy with responsibility for the institutional structure of the financial regulatory system and related legislation. During a crisis, the memorandum of understanding states that the UK FSA would be responsible for “the conduct of operations in response to problem cases affecting firms, markets and clearing and settlements systems within its responsibilities” which it may undertake by “the changing of capital or other regulatory requirements and the facilitation of a market solution involving, for example, an introduction of new capital into a troubled firm by one or more third parties.” [26] However, the Bank of England would remain in charge of “official financial operations … in order to limit the risk of problems in or affecting particular institutions spreading to other parts of the financial system.” [27]

Third, the UK FSA maintains a complex internal structure that appears to be based on a combination of regulation by financial sector and activity and customer base. As the organizational chart of the UK FSA shows (see Appendix A), regulatory responsibility is divided between two branches – one branch focused on retail markets and another branch focused on wholesale and institutional markets. This structure implies that the level of regulation should be different for those financial services and activities that are made available to retail investors and those made available to the more sophisticated institutional investors. Within each branch, sub-offices exist that focus on specific financial activities. For example in the retail markets group, there are separate offices for insurance, banking and mortgage, asset management and credit unions. The UK FSA also has “cross-sector leaders” that work across the retail markets and wholesale and institutional markets. These cross-sector leaders are focused on specific financial sectors, including asset management, capital markets, insurance, mortgages and financial stability. The UK FSA’s internal structure does not seem to be set up to have one group of regulators focus on prudential regulatory objectives and another to focus on business conduct regulatory objectives. Rather, it appears that both of these objectives are managed simultaneously by the mid-level regulators. Such a structure marks a big difference from the twin peaks model where any coordination of prudential regulation and business conduct regulation takes place at the highest level.

The confusing organization of the UK FSA does raise questions as to whether the UK FSA has successfully integrated the different regulatory objectives under one roof or whether the same problems associated with separate regulatory agencies continue to exist. Much attention has been given to the UK FSA’s failure to prevent, or at least mitigate, the collapse of UK bank Northern Rock. Critics have pointed out that UK FSA supervisors with expertise in insurance, not banking, were monitoring Northern Rock. Other critics have noted that the UK FSA failed to conduct an in-depth analysis of the bank until it was too late. [28] In addition, others noted that bureaucratic demands interfered with supervisory responsibilities. [29] And the UK Parliament Treasury Committee faulted the lack of coordination between the UK FSA and the Bank of England in responding to the Northern Rock collapse once the bank’s problems became apparent, revealing serious flaws with the memorandum of understanding between the UK FSA, Ban of England and HM Treasury. [30] The Northern Rock case mars what has otherwise been an impressive regulatory record by the UK FSA.

One of the most notable achievements of the UK FSA has been its adoption of principles-based regulation. [31] The UK FSA defines principles-based regulation as a system in which desirable regulatory outcomes are laid out in principles and outcome-focused rules, as opposed to detailed rules. The UK FSA believes that one of the major benefits of principles-based regulation is to allow firms to determine the most cost-effective means of satisfying the regulatory outcomes desired by the UK FSA. It is the UK FSA’s belief that this shifting of responsibility onto the firm will encourage competition and innovation in the marketplace, resulting in more effective responses to industry regulation. In turn, as regulated industries become more practiced in interpreting the UK FSA’s expectation, the principles themselves will be more effective than mere standards of minimal conduct as it will be harder for firms to evade the object and purpose of the regulations through clever lawyering and technical compliance.

The UK FSA’s principles-based regulatory approach is founded upon eleven “Principles for Businesses”:

-

A firm must conduct its business with integrity.

-

A firm must conduct its business with due skill, care and diligence.

-

A firm must take reasonable care to organize and control its affairs responsibly and effectively, with adequate risk management systems.

-

A firm must maintain adequate financial resources.

-

A firm must observe proper standards of market conduct.

-

A firm must pay due regard to the interests of its customers and treat them fairly.

-

A firm must pay due regard to the information needs of its clients, and communicate information to them in a way which is clear, fair and not misleading.

-

A firm must manage conflicts of interest fairly both between itself and its customers and between a customer and another client.

-

A firm must take reasonable care to ensure the suitability of its advice and discretionary decisions for any customer who is entitled to rely upon its judgment.

-

A firm must arrange adequate protection for clients’ assets when it is responsible for them.

-

11. A firm must deal with its regulators in an open co-operative way, and must disclose to the UK FSA appropriately anything relating to the firm of which the UK FSA should reasonably expect notice. [32]

To the extent these principles provide insufficient clarity regarding what the UK FSA considers proper conduct, the UK FSA intends to supplement the principles with interpretative guidance and rules expressed in “as outcome-focused a way as possible.” [33] Firms that act according to UK FSA-issued guidelines will be assumed to be in compliance with the rules. Also, the UK FSA will publish a handbook detailing what it considers to be “minimal acceptable standards” for compliance with the principles. While firms are encouraged to go beyond those guidelines and minimum requirements, the UK FSA believes that it is for the firm to decide how much further it wishes to go.