Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Creating an Advantage in Global Capital Markets

Principles-Based Securities Regulation

A Research Study Prepared for the

Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Cristie Ford

Principles-Based Securities Regulation

Biography

Cristie Ford

Cristie Ford is an Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia Faculty of Law and Co-Director, with Mary Condon, of the National Centre for Business Law. She joined UBC in 2005. Professor Ford pursued her LL.M. (2000) and JSD studies (in progress) at Columbia University School of Law, where she has received numerous fellowships and awards including BC Law Foundation and MacKenzie King Graduate Fellowships, a SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship, a Columbia University Public Policy Consortium Fellowship, and the James Kent Scholar award (for highest honours). She also practised law for six years at Guild, Yule and Company in Vancouver and at Davis Polk & Wardwell in New York. Professor Ford’s academic interests include comparative administrative and public law, regulatory theory and design, securities regulation, and corporate governance.

Executive Summary

What is Principles-Based Regulation (PBR)?

Principles-based regulation of capital markets is a hot topic in many jurisdictions, including Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. The theory behind principles-based and rules-based law is quite well known. Principles-based regulation is generally believed to be more flexible and more sensitive to context, but potentially less certain. Rules are more certain but may be rigid. Advocates and practitioners of principles-based securities regulation argue that proper regulatory design avoids the theoretical problems associated with principles, and can produce “simply better” regulation – meaning more effective regulation, at a lower cost.

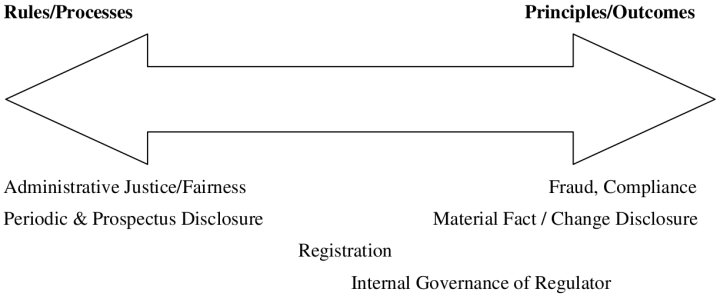

Every system will be (and should be) an amalgam of rules and principles, but a principles-based system looks to principles first and uses them, instead of detailed rules, wherever feasible. In the context of statutory drafting, principles-based regulation means legislation that contains more directives that are cast at a high level of generality.

PBR is also more than a statutory drafting choice. Promulgating principles-based legislation alone, without also paying attention to implementation and regulatory approach, will not foster better regulation. PBR needs to be accompanied by (1) greater reliance on outcome-based and management-based regulation, rather than process –based regulation; (2) transparent, accessible, ongoing guidance from the regulator; (3) methods for incorporating industry experience into regulatory expectations; (4) analytical methods to evaluate regulatory success and allocate regulatory resources; and (5) meaningful oversight of public companies and regulated entities, based on an “enforcement pyramid” that includes compliance examinations, and civil and criminal enforcement.

Best practices and critical success factors

The report identifies six elements that are especially important to a well-functioning principles-based regulatory structure:

-

Regulatory culture : A principles-based regulator focuses on defining broad themes, articulating them in a flexible and outcome-oriented way, accepting input from industry, and managing incoming information effectively. This requires expertise, a more trusting and communicative relationship with industry, restraint in providing administrative guidance, and the continued use of notice-and-comment rulemaking where appropriate.

-

Accounting for the impact on market participants: In order to be able to take advantage of the benefits of principles-based regulation, industry needs reasonable lead times to adjust to the new model, education and support, and the ability to rely on legacy rules during the transition period.

-

Learning systems and information management: A principles-based and outcome-oriented regulator needs information to be credible as it develops its guidance, evaluates results, and interacts with industry.

-

Outcome-oriented regulation: A focus on results, rather than processes, is crucial in a principles-based regulatory environment to keep the system flexible and capable of learning.

-

Regulatory credibility: In order to have its judgments respected under a principles-based system, a regulator’s conduct must be reasonable, predictable, and responsive.

-

Maintaining control: A principles-based regulator needs the statutory power to promulgate rules and guidance, and it (not the courts) needs to be the primary interpreter of its principles.

Risks and opportunities of PBR

This report considers background features in the Canadian capital markets, and tries to analyze the costs and benefits of a move to PBR for various stakeholders. A well-implemented PBR system, characterized by the best practices and critical success factors above, promises advantages to most if not all interested parties. A poorly-implemented PBR system imposes costs across the board. This report looks more closely at four key issues affecting risks and opportunities:

-

Certainty and PBR: Uncertainty imposes costs, and can compromise the rule of law in the enforcement context. However, certainty has less to do with how a statute is drafted and more to do with whether everyone understands what it means. An “interpretive community,” which has a shared understanding of regulatory expectations, needs to exist or be developed. For enforcement purposes, regulatory expectations need to be communicated, explained, and justified in a regular, transparent, and understandable way.

-

Enforcement and PBR: Credible regulation, including meaningful enforcement, is crucial to PBR. This report considers the particular challenges of enforcement under PBR, especially on the question of bringing enforcement actions for violation of a principle alone. It is imperative that fairness concerns associated with principles-based enforcement be addressed, and that a strong relationship between enforcement and policy functions be maintained.

-

PBR, a national securities regulator, and the passport system: PBR can be a pragmatic response to the challenges of trying to impose a regime on top of, or superceding, several pre-existing and different regimes. However, promulgating a federal principles-based model act does not automatically reduce the chance of divergence in application from one jurisdiction to another. Consistency in application requires an operational communicative/oversight infrastructure. Within a passport system, a principles-based model act would give provincial and territorial regulators a lodestar by which to orient their own practices, increasing harmonization and facilitating interprovincial mutual recognition. On certain issues, however, it could also reduce the pressure to harmonize. Some differences in approach between jurisdictions may become acceptable, provided each regulator is abiding by common principles.

-

Power, proportionate regulation, and participation: Under PBR, the content of principles will continually be filled in through actual practice over time. Therefore, unless the regulatory structure builds in opportunities for ongoing participation by a broader range of interests, more sophisticated parties will have more control over the process of developing content for those principles. Consumers and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) involved in the capital markets need to be explicitly considered. A strategy for engaging consumers should be multi-faceted. Proportionate regulation and PBR can also work together to be more sensitive to the needs of SMEs.

How legislation is structured to incorporate more principles: striking the balance between rules and principles in statutory drafting

Establishing a balance between rules and principles involves decisions about priorities and concerns. This report proposes a set of considerations for choosing between principles and rules, and compares approaches adopted by different jurisdictions. PBR looks different, and operates differently from more rules-based regulation in four main ways:

-

Legislation is drafted in plain language and often substantially reorganized.

-

In a principles-based system, less detail is provided in the statute, and more is left to be filled in through the authority’s rulemaking powers.

-

Even when it uses more rule-based methods, legislation is structured to be more outcome-oriented, and less process-oriented.

-

The principles-based approaches discussed here all set out high level principles to guide the conduct of regulated entities.

Recommendations

This report concludes with the following recommendations. Canada should:

-

Move toward a more principles-based approach to securities regulation.

-

For statutory drafting purposes, develop a set of criteria reflecting legislative priorities and appropriate choices in regulatory design, for deciding when to use rules and when to use principles.

-

Foster mechanisms that help market participants understand regulatory expectations, and that build an “interpretive community.”

-

Work toward developing a regulatory culture that matches the needs of the new environment in terms of expertise and approach.

-

Design an effective and appropriate enforcement structure, closer to the U.K. approach than the more enforcement-heavy American one.

-

Pay particular attention to small firms. Implement a proportionate and risk-based regulatory scheme, provide education and support, and develop appropriate consultation and participation mechanisms.

-

Build in ways to facilitate consumer engagement on an ongoing basis.

Principles-Based Securities Regulation

A principles-based system relies on dedicated, well-funded regulators who are interested in regulating. … Simplifying the current thicket of rules makes sense. But it will only create more trouble if we’re not willing to appoint the people—and commit the resources—needed to make the changes work. A principles-based system offers the potential for smarter regulation—the kind that helps markets work more efficiently. But the best principles in the world won’t help much if those in charge aren’t willing to enforce them.

James Surowiecki, “Parsing Paulson,” The New Yorker (April 29, 2008)

Table of Contents

- PART 1. ANALYSIS

- What is a “more principles-based approach”?

- Best practices and critical success factors

- Is this the right approach for Canada? Risks and opportunities

- PART 2. IMPLEMENTATION

PART 1. ANALYSIS

What is a “more principles-based approach”? [1]

Principles-based capital markets regulation is a hot topic, in theory and in practice, in many jurisdictions including Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. [2]

The classic example of the difference between rules and principles involves speed limits. A rule will say, “do not drive faster than 90 km/h”, whereas a principle will say, “do not drive faster than is reasonable and prudent in all the circumstances.” In this way, rules generally determine, in advance and quite precisely, what conduct is permissible. The frontline decision-maker (here, a police officer) only has to answer a factual question (“was this particular car driving faster than 90 km/h?”) On the other hand, under a principles-based system the frontline decision-maker also has to make a judgment about what is permissible. [3] In the speeding situation, the police officer first has to decide what “reasonable” and “prudent” driving in “all the circumstances” actually is, and then whether the specific car in question was driving in such a manner.

Scholars have identified some main theoretical advantages and disadvantages of rules and principles. Rules are generally considered to be more precise and certain, but may be rigid, reactive, and insensitive to the needs of particular situations . They can also be “gamed” and promote “loophole” behaviour. Principles are more flexible, more sensitive to context, and potentially more fair, but they can be uncertain, unpredictable, and difficult to interpret for those subject to them. They can promote arbitrary and over-reaching discretion by regulators. [4] Scholars working specifically in securities regulation, accounting and tax have looked at how rules or principles affect industry behaviour, and how to choose between rules and principles in particular situations. [5] Of course, in real life rules and principles are points on a continuum, not discrete concepts, and there is a good deal of overlap and convergence between them , [6] though it is still possible to talk about a “more principles-based” or “more rules-based” regulatory approach.

In addition, how principles are implemented in practice makes an enormous difference. Application influences theory in direct and indirect ways. For example, through application to real-life situations, principles acquire specific content on a constant, ongoing basis. Decision-makers may also interpret a rule “up” or “down” (making it look more like a principle or more like a detailed rule) to make it fit a specific situation. Principles, also, when interpreted by multiple human beings in multiple situations, may lose their high level character, slide closer to rules, get fuzzy around the edges, and otherwise drift and change. Therefore, whether a regulatory system fosters clarity and predictability , for example, is not entirely related to whether it is rules-based or principles-based. The real question is whether regulator and regulatees have a shared understanding of what the regulations entail. It is therefore very important to think carefully about the structure through which principles will be implemented. If properly designed, principles-based regulation in practice avoids the biggest problems associated with principles in theory, and can produce “simply better” regulation – meaning more effective regulation, at a lower cost. On the other hand, poor implementation can produce a system that is less transparent, less predictable, and less fair.

This report starts by establishing a working definition for a successful “principles-based” approach to securities legislation. The report then describes some important related concepts in greater detail.

Working definition of “more principles-based” regulation

Every system will be an amalgam of rules and principles. For purposes of this report, a “principles-based” approach to securities legislation is an approach that looks to principles first, and uses principles rather than detailed rules wherever feasible. [7] In terms of statutory drafting, this means legislation that contains more directives that are cast at a high level of generality. It also means a legislative/regulatory approach that does not respond to every new situation by adding more detail to the written law.

“Principles-based regulation” also requires more than principles-based statutory drafting. It must be accompanied by careful implementation. In fact, the British Columbia Securities Commission example, discussed below, shows that legislative drafting is not even a necessary component. Principles-based regulation can be achieved through regulatory practice alone. Compared to a rules-based or process-based approach, principles-based regulation relies more heavily on outcome-based and/or management-based regulation. It needs to be accompanied by (1) transparent, accessible, ongoing guidance and communication from the regulator, (2) efforts to incorporate industry experience, including good practices; (3) analytical methods such as outcome analysis and risk-based analysis, to evaluate regulatory success and allocate regulatory resources; and (4) meaningful regulation using a variety of tools, based on an “enforcement pyramid.”

The link between legislative design and implementation should not be severed. Principles-based legislation, without corresponding attention to questions of implementation and regulatory approach, will not foster better regulation on its own.

Related concepts

Outcome-oriented / results-oriented regulation

A great deal has been written on outcome-oriented regulation, and both Canadian and international regulators have extensive experience working with it. What is relevant for this report is that:

-

In the same way that a government could develop and use performance benchmarks to evaluate the success of its regulatory system, a regulator could develop and use performance benchmarks to evaluate the performance of issuers and registrants.

-

Outcome-oriented regulation should be contrasted with process-oriented regulation. Outcome-oriented regulation measures performance against regulatory goals, whereas process-based regulation measures compliance with detailed procedural requirements. Outcome-oriented regulation is attractive because it establishes a more direct relationship between regulatory goals and regulatory requirements. It therefore makes more efficient use of regulatory and industry resources. By contrast, process-oriented requirements are developed by regulators in advance, based on less contextual information, and may not be perfectly tailored to regulatory goals. Process-oriented regulation can also permit “cosmetic” compliance by market participants.

-

For present purposes, outcome-oriented regulation can function alongside management-oriented regulation, described below. There are differences between the two concepts, but both place responsibility for detailed decision-making with industry actors (who possess the best information about their own businesses), and give those actors the flexibility to design mechanisms that work for them.

-

Good outcome analysis can be challenging. Defining a clear set of objectives, developing criteria to evaluate outcomes and outputs, and measuring performance is demanding work. [8] Progress should be measured by reference to high-level impacts and outcomes, not just outputs.

-

Principles-based and outcome-oriented regulation are different concepts and should not be conflated. For example, one could have a system that is simultaneously rule-based and outcome-oriented. However, “principles-based process-oriented regulation” is nonsensical. By definition, outcome-oriented regulation accepts that there may be more than one way (i.e., more than one process) to achieve a regulatory goal. Principles-based regulation, also, focuses on high-level expectations and tries to avoid detailed, prescriptive, process-based requirements.

-

Outcome-oriented regulation is not automatically proportionate regulation. Like process-oriented regulation, outcome-oriented regulation can be “one size fits all,” which may put a greater burden on smaller firms without the same resources. Thought needs to be given to how to make outcome-oriented processes work with proportionate regulation, perhaps using such techniques as risk-based regulation, as the United Kingdom’s Financial Services Authority (“FSA”) does. [9]

Management based regulation

Under a management-based regulatory approach, [10] the regulator focuses on providing incentives to regulated parties to achieve socially desired goals. This shifts the centre of decision-making from the regulator to regulatees, by requiring regulatees to do their own planning and decision making about how to achieve goals. The difference between outcome-oriented and management-based regulation is that outcome-oriented regulation focuses on the final stage, i.e., whether the firm achieved regulatory goals. Management-based regulation focuses on the planning stage; i.e., the regulatee’s internal compliance processes including monitoring, risk assessment, training, etc. (Both can be contrasted with process-based regulation.) One advantage of management-based regulation is that it involves higher management in decision-making and accountability around such processes.

As with other approaches, management-based regulation can impose high costs on small firms. Requiring smaller market actors to implement sophisticated compliance mechanisms could impose a considerable burden, and outweigh the risks that any individual small issuer or firm poses to the market or investors. [11] As discussed below, particularly within the Canadian context, it is important that any legislative changes take into account the dramatic effect they may have on smaller issuers.

“Good” or “best” practices

For purposes of this report,

-

“Best” practices refer to the most state-of-the-art and highest, and perhaps the most comprehensive and elaborate, practices being used by industry leaders. “Good” practices are industry practices that have been shown to work in achieving regulatory goals.

-

The key difference between best/good practices on one hand, and “industry standards” on the other, is that the terms best and good practices refer to a process that is inherently dynamic, flexible, and evolving. Good and best practices are also effective in meeting regulatory goals. Industry standards simply reflect what industry is doing.

-

Principles-based regulation relies on best and good practices coming from industry to help define the content of principles-based regulatory requirements. Using best and good practices, as opposed to industry standards, allows regulatory standards to evolve and remain flexible. It also builds in a learning process for both regulators (who are learning from industry about what works in different contexts) and regulatees (who are learning from each other.)

-

Best and good practices are meant to be instructive, not mandatory. One size will not fit all. One of the risks of having a regulator share examples of good practices is that regulatees will interpret the good practices as de facto mandatory, process-based expectations to be applied across the board. [12] This also potentially shifts accountability away from management for developing its own appropriate procedures. Partly for this reason, some regulators believe that i ndustry associations, trade councils, or consultants are in a better position to disseminate best (as opposed to good ) practices.

-

A related risk is that using good practices (or certainly best practices) can produce regulatory expectations that keep ratcheting up endlessly. This amounts to regulatory “creep,” and de facto “raises the bar” without the safeguards of notice-and-comment rulemaking or advance guidance to firms. This can be especially onerous for small firms.

Administrative guidance

“Administrative guidance” refers to pronouncements from regulators that help regulatees understand how law or regulations are likely to be interpreted and applied. In its narrowest sense, guidance refers to the official written comments that often accompany statements of principles from regulators such as the FSA. In Canada, Companion Policies to CSA National Instruments are guidance. More broadly, guidance includes all information disseminated by the regulator about its approach, including speeches, “no action” or “Dear CEO” letters, and published enforcement decisions. Guidance is especially important for a principles-based approach, because it adds “flesh” to the “bones” of principle without resorting to detailed or complex rule-making. It should be transparently communicated, and is non-binding.

Guidance can be a flexible and useful mechanism for clarifying regulatory expectations. However, a regulator must be careful to keep its guidance clear and to manage it well. Otherwise, guidance (in the broader sense of the word) may reside in too many places and in too many forms, making it difficult to make sense of. This would produce less transparency and certainty for industry, not more. [13] If the regulator does not signal well with its guidance, it could be criticized for taking industry by surprise with a particular interpretation, leading to procedural problems with enforcement actions. On the other hand, regulators could also over-juridify their guidance in response to industry hunger for certainty. Doing so would compromise the flexibility of principles-based regulation.

Strategies to promote regulatory efficiency

-

Risk-based regulation : The general idea of risk-based regulation is widely understood. Its nuances are beyond the scope of this report. For present purposes, the term refers to a regulatory approach that uses risk analysis to proactively identify those market actors that need the most hands-on oversight, because of the risk they pose to regulatory goals. It is a method for trying to allocate regulatory resources efficiently. The Ontario Securities Commission, among others, is a risk-based regulator and has published its risk assessment criteria. [14]

The relationship between risk-based regulation and principles-based regulation is not direct. In fact, risk-based and principles-based regulatory approaches may not yet be speaking to each other very clearly. [15] However, risk analysis can be a tool that allows a principles-based regulator to try to ensure that the overall arrangement of regulatory interventions and guidance reflects real problems in the markets and a proportionate, rational regulatory response. As noted below, [16] the FSA’s risk-based approach also has implications for the regulation of small firms.

-

The Enforcement Pyramid : Like risk-based regulation, the basic concept of the enforcement pyramid is quite widely understood although its actual operation can be complex. [17] The basic idea of the enforcement pyramid is that regulators should use the least possible regulatory intervention to achieve their goals. Most regulatees (the thick bottom layer of the pyramid), who are generally well-intentioned and fairly capable, are coaxed or persuaded into compliance through regular compliance examinations and followup, warning and publicity, or other methods. A progressively smaller number of progressively more difficult or intransigent firms are dealt with through increasingly severe sanctions. This preserves enforcement resources and ensures the regulator reserves its greatest “fire” for the cases that call for it.

In order to be credible, a regulator using the enforcement pyramid must be able to accurately identify problematic conduct and noncompliance, and to tell the difference between that and innocent mistake or market failure. Recent research seems to indicate that a “tit-for-tat” strategy, in which the regulator begins with a cooperative stance and then mirrors every response by the regulatee in moving up the pyramid, is most effective. [18] An enforcement pyramid helps ensure that enforcement action is proportionate and reasonable, and that the content of principles develops appropriately.

Country/jurisdiction survey

Below are “thumbnail” descriptions of the more principles-based approaches to securities regulation adopted by the British Columbia Securities Commission (“BCSC”), the U.K. Financial Services Authority (“FSA”), and in North American derivatives regulation.

British Columbia Securities Commission

In 2004, after conducting regulatory impact analyses and engaging in public consultations, [19] the British Columbia legislature introduced a bill to create an innovative new principles-based Securities Act for the province. [20] Bill 38 and its associated proposed rules and regulations (together, the “B.C. Model”) would have established the most comprehensively principles-based regime in securities regulation in North America. The characteristics of the B.C. Model – plain language drafting, stripped down statutory architecture, outcome-oriented provisions and practice, a Code of Conduct for Dealers and Advisors – are discussed in more detail below. [21]

In support of its approach, the BCSC argued that prescriptive requirements emphasize the wrong things. That is, they encourage firms to focus on detailed compliance rather than to exercise sound judgment with a view to the best interests of their clients and the markets. Detailed and “top-down” requirements also calcify the regulatory system to reflect one-size-fits-all industry practice in a particular point in time. By contrast, the BCSC argued, principles-based regulation supported by industry-driven learning stimulates innovation, reduces the regulatory burden, and ensures flexibility. [22] The BCSC also argued that compliance will increase if rules are fewer, easily understood, and adequately communicated. [23]

Bill 38, British Columbia’s proposed new legislation, received Royal Assent on May 13, 2004, and was set to come into force by regulation, [24] but it has not done so. [25] The BCSC has chosen instead to focus its efforts on the passport system. [26] In any event, the BCSC now takes the position that “the most important aspect of regulatory reform is a change in how [regulators] administer securities legislation.” [27] It has stated that “although the 2004 act is not in force, the BCSC has moved ahead with changing [its] regulatory processes and approach in much the same way [it] would have done under the 2004 act.” [28] Like the FSA, the BCSC emphasizes outcome-based analysis at the level of practice.

The U.K. Financial Services Authority

The United Kingdom’s Financial Services Authority (the “FSA”) has been a thought leader on principles-based financial services regulation. The FSA’s design was influenced by concurrent U.K. regulatory reform efforts, as exemplified in the “Principles of Good Regulation”: proportionality, accountability, consistency, transparency, and targeting. [29] Its enabling statute, the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“ FSMA ”), emphasizes these priorities. [30] Apart from the FSMA , the key document for market participants working with the FSA is the Handbook. [31] The main components of the FSA regulatory approach are:

-

a hybrid rules and principles structure, with an emphasis on the use of principles wherever possible. In 1998, the FSA decided that in the interest of continuity, it would maintain existing material and rules where possible. [32] In the intervening years, it has gone about replacing broad swaths of these detailed legacy rules with short high level requirements, often accompanied by regulatory guidance. [33] The FSA says that its work is unfinished and that its Handbook “will rely increasingly on principles and outcome-focused rules rather than detailed rules prescribing how outcomes must be achieved.” [34] In referring to its industry-leading approach as simply “ more principles-based regulation,” the FSA is also acknowledging that no statutory scheme is a pure type, and that good regulation requires a combination of rules and principles. [35]

-

Consultation . The FSMA requires the FSA to consult practitioners (i.e., registrants) and consumers, to establish a Practitioner Panel and a Consumer Panel, and to consider their representations. [36] It has engaged in consultations on several topics, including how to simplify its rules relating to its relationship to retail customers, and how to streamline and improve existing money laundering provisions. [37] The FSA has also formulated its guidance through collaboration with financial market actors, for example on the topic of trading ahead of investment research. [38] The FSA also consults on many aspects of its own operations. [39]

-

Management-based regulation. The FSA has also shifted some of the innovative burden from itself to industry – for example, in challenging industry to propose a credible solution to conflict of interest issues arising from soft commission and bundled brokerage arrangements. [40] According to the FSA’s interpretation of the Principles of Good Regulation, a well-designed regulatory approach “recognizes the proper responsibilities of consumers themselves and of firms’ own management.” This helps it to become more forward-looking and preventive, shifting its own resources “from reactive post-event action towards front-end intervention.” [41]

-

Risk based regulation. The FSA uses its ARROW (or ARROW II) methodology to “prioritize the risks [to its statutory objectives], inform decisions on the regulatory response and, together with an assessment of the costs and benefits of using alternative regulatory tools, help determine resource allocation.” The FSA takes a “differentiated approach” to supervision under which fewer regulatory resources are devoted to firms designated “low impact.” [42] This also means that the FSA is not a “zero failure” regime. [43]

-

The FSA approach to risk-based regulation is also proportionate . The FSA does not subject small firms to the same scrutiny as larger ones, or require the same kinds of structured and detailed responses from them, because of their sheer number and because on an individual level each one poses a relatively small risk to consumers. [44]

-

-

Outcome-oriented regulation . It has linked its statutory objectives and the Principles of Good Regulation into three (formerly four) strategic aims: helping retail consumers achieve a fair deal, promoting efficient, orderly and fair markets, and improving [its] business capability and effectiveness. It measures its regulatory effectiveness against nine high level outcomes under the three aims, as well as two “lower” tiers of activity measures, and process measures. A substantial body of supporting frameworks and systems, including surveys and metrics (some of them pre-existing and some created to support outcome-oriented regulation), exists to support the process. [45] The FSA also interacts with industry in an outcomes-oriented manner, as the Treating Customers Fairly initiative demonstrates. [46]

-

A consistent enforcement approach. The FSA enforcement regime is quite different from the U.S. approach. [47] The FSA does not take formal enforcement action nearly as often as the U.S. SEC, and its penalties are not as severe. [48] Rather than focusing on ex-post enforcement actions, the FSA tries to maintain an open and cooperative relationship with firms based on dialogue, proactive supervision, and a focus on compliance. [49] Significantly, the FSA is also prepared to pursue enforcement actions based on breach of principles alone (without necessarily a breach in specific rules), and expects to see more such cases in the future. [50] Margaret Cole, the FSA’s Director of Enforcement, suggested the value of these types of actions in the drive to achieve “credible deterrence.” [51]

The FSA describes its approach as something very different from deregulation, outsourcing, or reduced regulation. John Tiner, the FSA’s former Chief Executive, described his organization’s principles-based approach to include, “[t]he heightened significance of communication in a principle-based system. Our efforts to rationalise and focus the FSA Handbook. Our enhanced Risk-Based approach. And, managing down regulatory costs.” [52] He argued that principles-based regulation produced simply “better” regulation, meaning simultaneously “(1) a stronger probability that statutory outcomes are secured; (2) lower cost; and (3) more stimulus to competition and innovation.” [53] In the wake of the nationalization of Northern Rock and the overall liquidity crisis this year, Mr. Sants reiterated his support for the FSA’s principles-based and outcome-oriented approach. [54]

Regulation of Derivatives Trading in North America

The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission operates in a principles-based manner and its primary statute, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act , [55] has several principles-based components. In particular, that Act incorporates a set of “core principles,” reproduced in this report’s Appendix, that share features with the FSA’s Principles for Business and the BCSC’s proposed Code of Conduct for Dealers and Advisors. [56] Quebec’s new Derivatives Act [57] is also substantially principles-based, and it is a first attempt internationally to regulate a full range of derivatives. It has not yet come into force, and regulations and rules have not been published. The statute is cast in plain language, and its drafting is streamlined and remarkably outcome-oriented. (It is also a more circumscribed statute because it relies on a pre-existing regulator and a companion Quebec Securities Act .) One of its more interesting features is that, so as not to inhibit fast-moving practice in the derivatives industry, the QDA has adopted a self-certification mechanism (similar to the American one), under which regulated entities must demonstrate that proposed new products are consistent with core principles. Some of the Act’s key principles-based provisions are set out in this report’s Appendix, along with the “core principles” from the May 2006 proposed framework of the Autorité des marchés financiers for the regulation of derivatives. [58]

Best practices and critical success factors

The best resource for understanding the best practices and critical success factors in principles-based securities regulation are the regulators, like those at the BCSC and FSA, that have worked with such an approach. This report limits itself to identifying some key themes.

Six critical success factors are discussed below. [59] Note that good legislative drafting is not on the list. This is for two reasons: first, drafting considerations are discussed in the context of implementation. [60] Second, although well-designed, principles-based legislative drafting makes it easier to implement a principles-based approach, the BCSC and FSA examples demonstrate that principles-based statutory drafting is less important than regulatory practice.

Regulatory culture

Working well with principles-based regulation requires considerable changes to traditional regulatory culture. Rather than trying to articulate non-negotiable, specific requirements, a principles-based regulator needs to focus on defining broad themes, articulating them on a flexible and dynamic basis, accepting input from industry, and effectively managing incoming information. This requires a different relationship between regulator and regulatees, different expertise, and a pragmatic and measured regulatory stance. Moving to a new model would also take time, and training. Former BCSC Commissioner Robin Ford’s presentation to the Allen Task Force in 2006 sets out her experience with change management at the FSA, including obstacles the FSA faced in implementing an outcome-oriented, principles-based system and the tools the FSA used to help staff adjust. [61] The four bullet points below identify some key elements that need to be considered.

-

Expertise : Principles-based regulation, like risk-based regulation, is characterized by a hands-off philosophy. However, this does not necessarily mean that fewer regulatory resources will be required. Depending on choices about implementation, principles-based regulation may actually require intensive interaction with firms, at least around certain issues or situations. [62]

Malcolm Sparrow’s empirical work in the United States also illustrates the point. [63] Sparrow describes how the most effective modern regulatory techniques use sophisticated problem-solving methods and self-reflective analysis to do the challenging and complex work of “pick[ing] important problems and solv[ing] them.” According to Sparrow, three common elements characterize the best new regulatory structures, and each one calls for multiple difficult professional judgments:

-

a clear focus on results—not in terms of process or quotas, but based on an expanded and more specific set of indicators including “big picture” Mission Statement-level impacts, behavioral outcomes such as compliance rates, agency activities, outputs, and resource efficiency;

-

adoption of a disciplined problem solving approach based on systematic identification and prioritization of important risks or patterns of noncompliance, a flexible and functional project-based approach, and periodic outcome evaluation with flexible resource allocation based on outcomes;

-

selective investment in collaborative partnerships. [64]

The Northern Rock debacle in the U.K. highlights the kinds of staffing and resource problems that can afflict a principles-based regulator, like any other regulator. [65] Indeed, principles-based regulation actually requires more skills than the box-ticking aspect of rule-based regulation does. The FSA’s responses to Northern Rock, and its challenges in meeting them, are instructive. The FSA plans to enhance its supervisory teams (meaning more staff, better training, a mandatory minimum number of staff per high-impact institution, and closer contact between senior staff and the biggest firms.) It also plans to improve the quality of its staff, hiring risk specialists to support frontline supervision teams by focusing on the complex models used by banks to gauge financial risk. However, as one commentator observed, the FSA may find recruitment a problem, since the regulator will be pursuing “the same PhD rocket scientists the banks are chasing. … As Northern Rock shows, it’s not just about evaluating the problems, but having the people who can follow them up and forcefully make the case to the bank.” [66]

-

-

Trust and Communication : Principles-based and outcome-oriented regulation requires regular and open communication with regulatees. Among the greatest advantages of principles-based regulation are its flexibility and its ability to move with, and learn from, industry experience. This requires the regulator to step back, and to “steer not row” more often. [67] The FSA, for example, consults with industry and consumers in developing its guidance, and shares information about good practices with industry stakeholders.

When it comes to enforcement, a principles-based regulator should build a “paper trail” for an enforcement action whenever possible. This is especially true where the regulator is concerned about a possible breach of a principle, without a corresponding breach of a detailed rule. [68] The regulator needs a systematic way to communicate with firms through various steps – compliance, warning letters, etc. – so that enforcement is not a surprise to anyone when it happens. Of course, there will still be those rare cases that call for urgent action, where conduct is egregious and a fundamental principle has been violated, in which it is not possible to develop the same kind of paper trail. Just as they have to do today when pursuing those cases under a public interest power, a regulator will have to justify its exercise of judgment after the fact in those situations.

-

Restraint with regard to guidance : Guidance is an essential component of a principles-based regulatory scheme. As Julia Black points out, however, if a regulator elaborates principles too often, through too much guidance in too many different forms, the result can be increasing prescriptiveness, potential inconsistency, and potentially a body of complex and inaccessible case law. Black notes that “[u]nless great care is taken in the formulation of guidance it could simply reintroduce detail and prescription in a much less transparent and accessible way.” [69] Resisting the impulse to provide too much guidance, in terms that are too concrete, can be especially challenging in the face of industry demands for greater certainty. Nevertheless, the regulator should keep the “big picture” in mind and should work to communicate guidance in an effective, accessible, and non-prescriptive manner. The same point applies to the accretion of guidance over time. The regulator should periodically review its guidance, to identify and address the relevance of older guidance.

-

Continued use of notice-and-comment rulemaking : The other risk with guidance under a principles-based regime is that it could become – or could be interpreted as becoming, even if it is not – de facto rulemaking through the “back door,” without the transparency and accountability safeguards provided by notice-and-comment rulemaking. The Ainslay case and the subsequent Osbourne report reflect Canada’s experience here, and stand for the principle that one cannot do an “end run” around notice-and-comment, creating wholly new sets of rules without administrative safeguards. [70]

Impact on market participants

Registrants and issuers operating under a principles-based regime have the flexibility to to design effective processes based on their own intimate understandings of their businesses and attendant risks. When implemented and overseen effectively, this can reduce the regulatory burden, permit innovation, and permit more effective regulation. On the other hand, there are costs associated with learning to work with principles, and a principles-based approach puts greater pressure on management to do its own thinking, exercise its own judgment, and develop its own dynamic and self-analytical processes. Process-based regulatory requirements may sometimes be easier to work with, even if they are less well-suited than outcome-based or management-based requirements. Firms and companies need the responsibility to decide how to best align their business objectives and processes with regulatory objectives, in order to take advantage of the benefits of flexibility that principles-based regulation offers. [71] This may require both a shift in orientation, and robust educational resources and other support – especially for smaller market actors.

As mentioned above, principles-based regulation also requires a relationship between regulator and regulatee that is generally trusting and collaborative, not adversarial or cat-and-mouse. Ongoing communication helps provide clarity around principles. Communication must go both ways to be effective, since the regulator relies on industry experience to further its own learning. Therefore, a principles-based approach requires market participants to share information with regulators. Not sharing information must be actionable on its own. The regulator should also develop short and long term incentives to induce market actors to be cooperative and communicative.

The transition to a principles-based approach could be challenging for regulated entities and public companies. As the FSA recognized in an early document, “Changes in the manner of expression of requirements may impose a burden on businesses … substantive changes … need to be accompanied by reasonable lead times for adjustments to systems and procedures.” [72] Along with providing lead time and educational and other support, a regulator transitioning to a principles-based approach may want to maintain existing rules as a “quasi safe harbour” until they can be incrementally reviewed, revised, and supplanted by guidance. [73]

Learning systems and information management

In order to keep a principles-based approach both flexible and functional, structures need to be developed that allow the regulator to gather useful information, analyze it effectively, learn from it, share it, and plough it back into subsequent regulatory decision-making. At the FSA, the Operations Business Unit serves this function. [74] Without a systematic method for working with a large and varied body of information, both transparency and learning (by industry and regulator) will be compromised.

Especially in fast-moving environments like capital markets regulation, a principles-based regulator needs information to be credible as it develops its guidance and interacts with industry. As mentioned above, collaboration with industry in various forms is a key means by which a principles-based regulator adapts its expectations and approach. For example, when a firm comes to the regulator with a proposed new approach to a compliance problem, it must demonstrate that the proposed method is consistent with regulatory principles and goals. The regulator also gains considerable insight from compliance examinations and enforcement actions. These kinds of interactions are rich sources of information, and that information needs to be captured. In the same way, a regulator needs to be able to measure and understand results achieved, in order to take an effective outcome-oriented approach. The regulator can then leverage all this information to assess risk more reliably and accurately, to publicize “good practices”, to support industry learning, and to provide clarity about principles without unduly compromising the system’s flexibility.

Outcome-oriented regulation

Outcome-oriented regulation is defined above, [75] and further discussed below in the statutory drafting context. [76] It is a critical success factor for principles-based regulation, because a focus on outcomes rather than processes is needed to keep the system flexible and capable of learning. The FSA continues to emphasize the link between principles-based regulation and outcome-oriented regulation, and to revise its rulebook to be more outcome-oriented and less process-oriented. [77] Because of misunderstandings that have arisen about the meaning of principles-based regulation, the BCSC submission to the Expert Panel on Securities Regulation even prefers to describe its approach as “outcomes-based” rather than “principles-based.” [78]

Regulatory credibility

Especially under a principles-based system, a regulator must exhibit trustworthiness and competence if it wants its judgments to be respected. Regulatory conduct should be as transparent as possible. The regulator must resist the temptation to seize easy but less consequential technical violation cases. Regulators should cooperate with responsible market actors where those actors continue to behave responsibly, and should maintain ongoing dialogue. They should be reasonable, and responsive. The ratcheting-up stages of the enforcement pyramid should be predictable and defensible. [79] Market actors should be able to predict, with some degree of accuracy, whether or not their conduct will be found to breach a principle. [80] All of this sends the message that regulatory conduct will not be arbitrary, which encourages responsible firms to believe that they will be rewarded for their responsibility. The regulator also needs to be able to work with an outcome-oriented rather than process-oriented method. Professor Black has described the credibility gap and confusion that result when regulatory staff at an ostensibly principles-based regulator interpret internal agency guidelines in ways that produce rigid, non-negotiable expectations for industry. [81]

Maintaining control

In order to establish a functioning principles-based regulatory system, the regulator must be able to maintain considerable control over its own processes and the interpretation of its principles. This means, first, that the regulator must have the statutory power to promulgate rules and guidance. Second, allowing courts to interpret regulatory principles and goals could dilute regulatory interpretations and undermine both coherence and flexibility. Securities commissions tend to attract considerable deference by courts on judicial review / statutory appeal, and surely some degree of court oversight is important. But it should be pointed out that with respect to enforcement actions, which can be appealable to the courts, the FSA tends to settle its principles-based actions. (It also makes extensive use of compliance and other methods before even getting to the enforcement stage.) It is difficult to predict whether a court, which by virtue of training and mandate may have a different perspective, would necessarily endorse the regulator’s particular interpretation of a principle or its use of it. [82]

A principles-based regulator should also be concerned about the impact of civil liability on its ability to define its own principles. At least one observer has suggested that an American-style approach to civil liability can make principles-based regulation unworkable. [83] In response, o ne early FSA document suggests that despite the legal importance of the principles for business, it should not be possible “for private persons to found an action for damages on the principles alone.” Violating a principle would only make a market actor liable to disciplinary sanctions. The FSA argued that the principles are a statement of “regulatory expectations” that need to be applied in line with the overall body of FSA rules and guidance. As such, it was not desirable for “civil litigation between private parties […] to become the engine driving the interpretation of the principles.” [84]

Is this the right approach for Canada? Risks and opportunities

Background features in the Canadian landscape

-

Nature of Canadian capital markets : Canada is a small market, comprising only about 3.17% of total market capitalization worldwide. Canada ’s public companies are bifurcated into a modest number of large companies, and a large group of very small companies, with the latter group disproportionately located in British Columbia and Alberta. Canadian companies are also substantially smaller in absolute dollar terms than their American counterparts, they tend to be closely held relative to American and U.K. ones, and they are often characterized by a dual class share structure. [85] In his June 2006 research paper for the Allen Task Force, Professor Christopher Nicholls remarked that these factors mean that compared to the United States, “Canadian securities regulation should be relatively more focused upon preventing the abuse of minority shareholders of public companies that may arise in connection with going-private transactions, related-party transactions, and unlawful insider trading.” He also observes that “[t]he number of small, thinly traded Canadian corporations further suggests that share price manipulation ought to be a key securities regulatory focus,” [86] and that “lighter or more flexible regulation that may be considered appropriate for U.S. micro-cap and, more particularly, small-cap companies could, potentially, still prove overly burdensome for significantly smaller Canadian small-cap companies.” [87]

-

Federal/provincial distribution of powers: This information is well known and does not need to be repeated here. It is relevant that securities regulation is a provincial matter in Canada, a passport system exists, and recent research has been done on relevant regional differences in capital markets, capital raising, and enforcement priorities. [88] The Crawford Panel has recently recommended a model for achieving a securities regulatory framework featuring a common securities regulator, a common body of securities law, and a single fee structure. [89]

-

Enforcement challenges and international perceptions: It is frequently observed that there is an international market discount for Canadian-listed companies based on perception of failures of enforcement, although some recent empirical studies have challenged this claim. [90]

-

Proximity to United States: Canada’s proximity to the United States is most relevant for our largest public companies, many of which cross-list on American exchanges. [91] Professor Nicholls has suggested that adequate investor protection already exists in these cases, and there is a need to ease certain formal requirements for the largest public companies. [92] Principles-based regulation could reduce costs for multinational actors, such as cross-listing Canadian companies, because the jurisdiction with the more detailed standards sets the de facto requirements (assuming the systems’ principles are generally consistent, as they are currently between Canada and the United States.) [93] One concern about principles-based regulation is that it could engender scepticism by American investors and regulators about Canadian companies’ domestic reporting requirements, which could affect the unique Multijurisdictional Disclosure System that Canadian companies enjoy. How United States representatives would respond to principles-based regulation in Canada, in terms of the MJDS, is unclear. Assuming (as seems likely) that the MJDS remains in place, companies that want to use the southbound MJDS option will probably choose to make additional disclosure – as many Canadian companies already do – or make disclosure in a U.S.-friendly format, to facilitate marketing and meet liability concerns when conducting a public offering in the United States.

There may be some possibility that American regulation will move more toward a principles-based approach. [94] Regardless, what works for a dominant market like the United States’ will not necessarily work for the Canadian one. I n Professor Nicholls’ words, “Canada’s regulators do not have the luxury of crafting regulation secure in the knowledge that the lure of Canada’s markets will ensure that modest regulatory burdens will not dampen the interest of issuers and investors.” [95] A more streamlined approach may even make Canada a North American listing destination of choice, if a better regulatory system (meaning one that regulates at least as effectively while imposing a lesser regulatory burden) gives it a competitive advantage.

Costs and benefits of rules- and principles-based systems: stakeholder analysis and key questions

This report does not try to precisely value the costs and benefits to various stakeholders in moving towards a more principles-based system. As Lawrence Schwartz observed to the Allen Task Force, this is work for highly trained specialists. [96] What is possible here is to identify some relevant factors in light of existing knowledge about rules-based and principles-based approaches.

The advantages of rules are generally thought to go to certainty and predictability, while the advantages to principles are that they are more flexible and better tailored to a given factual situation. The costs of each approach are the flip-side of their benefits. However, this accepted wisdom tends to oversimplify the distinction. It does not recognize that rules and principles operate along a spectrum, or that concepts like “certainty” and “flexibility” can be quite complicated. [97] Also, the rigid dichotomy fails to consider how important application is. Depending on context, a legal requirement drafted as a principle may actually operate much more like a rigid rule, and the converse is true as well. “Costs” and “benefits” can also be nuanced concepts, and there is a relationship between the valuation of particular goods, the distribution of costs or benefits to different stakeholders, and larger policy priorities that are beyond the scope of this report.

That said, the table below tries to identify some key considerations on either side of the ledger, based on existing literature and experience. It looks at costs associated with an up-and-running principles-based system, not costs associated with transition to such a system. Perhaps most usefully, it illustrates how complex these calculations can be, and how much the evaluation of a particular cost or benefit depends on how the principles-based legislation is structured. Following the table, this report separately addresses some of the main outstanding questions about principles-based regulation in Canada, which tend to centre around

-

certainty and predictability,

-

problems of enforcement,

-

the passport system and the prospect of a single regulator, and

-

power, proportionate regulation, and participation.

|

Stakeholder Analysis: Potential Costs and Benefits of Principles-based Regulation, Relative to Status Quo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Stakeholder |

Potential Benefit |

Potential Cost |

Possible Responses to Costs Presented / Other Comments |

|

Issuers and Registrants |

|

|

|

|

US Crosslisted Issuers / Southbound MJDS Issuers (assuming larger, sophisticated)

|

US Crosslisted Issuers / Southbound MJDS Issuers

|

|

|

|

Small Issuers

|

Small Issuers

|

|

|

|

Other Professionals Involved in Industry |

|

|

|

|

Regulators |

|

|

|

|

Consumers, Investors, Canadian Capital Markets |

|

|

|

Certainty and principles-based regulation

Worries about certainty and predictability under a principles-based regime are real ones. Principles alone can be problematic if, when implemented, they amount to non-transparent, arbitrary, and/or wide-ranging exercises of discretion by regulators. A lack of certainty also increases costs in other ways. On the one hand, it can provoke fears of regulatory overreaching, which will make industry actors more risk averse, more likely to interpret the principles in narrow ways, and less likely to innovate. [98] On the other hand, a lack of certainty can provoke fears of laxity, undermining the credibility of Canada’s enforcement efforts and negatively affecting its capital markets.

The pressure toward certainty is even more pronounced in the enforcement context, where the possibility of sanctions exists. This makes sense for reasons of procedural fairness and the rule of law. Regulatory expectations under a principles-based system can be flexible, but they cannot be so flexible that market participants cannot make reasonably accurate predictions about what behaviour is permissible. The rule of law does not demand absolute certainty, but it does require a degree of predictability in enforcement – meaning that if regulatory expectations are going to be flexible and evolving, they must nevertheless be communicated, explained, and justified in a regular, transparent, and understandable manner. [99]

As important as certainty is, however, it is also important to distinguish between “real” certainty and “superficial” certainty, which gives the illusion of clarity because it masks an exercise of discretion, or pretends that facts on the ground are more settled than they are. New situations (new industries, new business products, new tasks – eg., subprime mortgage servicing) will produce transitional periods during which system participants work out what is reasonable. When faced with new situations, strict rules that were drafted without that situation in mind may provide only the veneer of certainty. A detailed rule that does not cover a new situation will require the interpreter to exercise discretion to square the ill-fitting rule with the new situation. Because this takes place under the guise of an ostensibly “clear” rule, that exercise of discretion is rarely reviewable, or even necessarily recorded or considered in any systematic way. On the contrary, it conceals the working-out process (something that astute market participants will identify) and further compounds the problem of uncertainty. Moreover, to handle the inevitable gaps between clear rules, the regulatory system relies, sometimes quite heavily, on residual public interest powers whose exercise can be even less predictable or transparent.

Certainty and predictability have costs as well. In particular, absolute certainty in regulation can mean that rules are clear but poorly designed to meet regulatory goals. For market actors, ill-fitting legacy rules can create delays and inhibit innovation. A more flexible but less certain principles-based requirement can more effectively address changing market circumstances and practices.

In order to function transparently and predictably, a principles-based system must build in mechanisms to communicate with industry about its expectations. Communication can take place through a number of channels including official guidance, specific enforcement actions, or comments on industry standards. Over time, the goal of such communication is to help develop an “interpretive community” that understands regulatory expectations, and can usefully interpret regulatory pronouncements about “reasonableness” or “effectiveness” in different situations. [100] Communication is also important for credibility, so that market participants in general understand the grounds for decisions made by the regulator, and do not experience them as arbitrary or unreasonable. Where uncertainty persists because facts are still changing, this can be clearly identified. This kind of uncertainty is the product of the factual situation, not principles-based regulation. Transitional phases call for ongoing communication and periodic re-evaluations as events unfold.

Regulators may find it challenging not to fall back to concrete rules, and to remain outcome-oriented rather than process-oriented. They may experience both internal and external pressure to commit to particular positions, for example in their administrative guidance, in the interest of certainty. [101] However, this is not in the long term best interest of a strong and flexible regulatory structure. Too much juridified, process-based, rule-oriented guidance from a regulator is the worst of both worlds: it loses the flexibility advantages of principles-based regulation while also bypassing safeguards such as notice-and-comment rulemaking. It also undermines legislative intent. Where a decision has been made to regulate something by way of principles, then that approach should be maintained. Other areas will be regulated by way of rules.

Enforcement and principles-based regulation

In addition to the concerns about certainty above, a few additional comments should be made on enforcement under a principles-based approach, on procedural fairness and principles-based regulation, and on the possibility of a federal enforcement tribunal.

-

On principles-based enforcement:

At the moment the perception is that Canada has neither the intensity of enforcement effort that we see in the United States, [102] nor the additional factors that make U.K. efforts work in the absence of that intensive enforcement. [103] Credible regulation, including meaningful enforcement, is even more important within principles-based systems because it ensures the system is not lax. Clearly the “Canadian discount” needs to be addressed, but this does not necessarily call for an American-style ex post enforcement strategy. While the FSA’s more pyramid-shaped, consultative, compliance-oriented approach may not be the only way to operate for a principles-based regulator, serious thought must be given to whether reaching for the “big stick” of an enforcement action as a first resort is necessarily consistent with principles-based regulation. [104]

Principles-based enforcement cases will look different in other ways as well. For example, technical rule violation actions – even though they may be the easiest to pursue – cannot be a pillar of enforcement strategy. Also, principles-based cases (at least in the U.K.) tend to settle. A series of settled cases may not send the right message to the market about Canada’s regulatory seriousness. Third, as discussed further below, there will be times when the regulator brings an enforcement action on the basis of a breach of principle alone – absent any clear rule violation. This approach has been effective at the FSA, for example with regard to Citigroup Global Markets Limited’s “Dr. Evil” trades in 2005. [105]

Working with principles-based regulation also requires expertise and confidence on the part of regulators. In effect, the regulator is being required to substitute its judgment about what a particular provision means for the judgment of someone in the industry. This can be anxiety-provoking for staff, when facing a panel and operating under the intense scrutiny of a watchful and clever defense bar. It may also be hard to predict what would happen if an enforcement case concerning a violation of a principle alone (i.e., not accompanied by any clear rule violation) made it to the courts. On the other hand, regulatory staff already exercise substantial discretion under the current system, both “under the radar” in deciding to apply rigid rules in a particular manner, and in applying the existing public interest powers. They can get comfort by looking at prior prosecutions, which suggest that in any event, staff is already proceeding based on principles or consistent with them. [106]

-

On Fairness:

Conduct can be harmful to the markets and violate a regulatory principle, even if it does not violate a specific clear rule. The need to be able to respond to such conduct underlies existing public interest powers in, for example, section 127 of the Ontario Act and section 161 of the British Columbia Act. However, broad powers can create the risk of unpredictable, nontransparent, potentially arbitrary enforcement and abuse of discretion by regulators. (Among other things, this means that we must compare any more principles-based system with the actual system in operation, not a perfect one. In the Cartaway example cited in BCSC research, the use of its proposed principles would actually have yielded more certainty and predictability than the public interest power, not less.) [107]

One form of regulatory overreaching is the hindsight risk, and principles-based enforcement is vulnerable to it. The hindsight risk is that whenever regulatory goals are not achieved, regulators may be inclined, perhaps unconsciously, to find that a principle has been violated. Risks that no one foresaw at the time may seem forseeable in hindsight, once the risky thing has happened. It is difficult to cast back in time and to “unknow” things that have become known, but principles cannot be applied retrospectively. One response comes from Professor James Park, who has developed a thoughtful framework for determining whether a principles-based enforcement action is appropriate in any given situation. [108]

Other mechanisms would could be developed to address fairness concerns at the systemic level might include:

-

A “quasi safe harbour” of prior rules, so long as the regulatee does not seem to be intentionally circumventing principles. [109]

-

A paper trail: prior compliance action and ongoing communication before enforcement action is taken should mean that enforcement action when required does not come as a surprise. [110]

-

The continued use and importance of notice-and-comment mechanisms for actual rulemaking. [111]

-

While it is not a complete answer, it should also be remembered that securities commission decisions can ultimately be appealed to and/or judicially reviewed by the courts. [112] Particularly when it comes to procedural fairness, this tempers potential overreaching by regulators, and provides regulated entities with an entrée into the judicial system.

-

On the possibility of a federal-level enforcement tribunal:

The Expert Panel on Securities Regulation is considering a range of options in regard to a common enforcement agency, or tribunal.

Bifurcating securities regulation into policy makers and enforcement staffers could present significant hurdles to principles-based regulation, if information about enforcement did not efficiently make its way back to policymakers and regulators. Enforcement actions provide excellent information to regulators about where potential trouble spots might be. They also provide important information to market participants about what other parts of the regulatory structure – the compliance department, for example – is likely to require under a particular principle. This is more than expertise; it is an essential component of a system that is capable of learning from its own experience, as an outcome-oriented and principles-based system is supposed to do.

Certain comments by the U.S. Treasury’s Blueprint paper may be relevant here as well. That paper recommends that over the long term, the American banking, insurance, securities, and futures markets should replace its existing regulatory agencies and move toward an “objectives-based” system, similar to that in Australia and the Netherlands. The Blueprint argues building regulatory structures around three core objectives (market stability regulation, prudential financial regulation, and business conduct regulation) greatly increases regulatory efficiency because it consolidates regulatory responsibilities around natural synergies, and aligns regulatory structures directly with regulatory goals. The Blueprint’s recommendations obviously contemplate more far-reaching restructuring of the American financial markets than Canada is considering now. However, its observations about efficiency and goal-orientation seem to argue against bifurcating enforcement and policy making functions in securities regulation.

An independent tribunal, established to review regulatory and enforcement decisions, may not pose the same problems. The FSA’s experience is relevant here and should be sought out. The FSA seems to be able to combine its regulatory approach with oversight of some of its decisions by an independent tribunal, the Financial Services and Markets Tribunal. As noted above, the FSA approach has been to integrate its enforcement efforts into its overall regulatory structure. It relies more on ex ante supervision, monitoring, and ongoing communication than on ex post deterrence, especially relative to the SEC. It sees enforcement as “an important component, not the sole element, of a credible deterrence philosophy.” [113] It measures its enforcement performance using the same outcome indicators as the rest of its regulatory performance. Moreover, the FSA’s experience has been that publishing its enforcement actions is an effective way of communicating with industry – it is a form of guidance – and that firms have reviewed and improved their own processes as a result of published enforcement cases. [114] Canada may be able to gain useful insights into how the relationship between regulator and independent tribunal works, in the context of a principles-based and collaborative regulatory approach, by speaking to those with experience with the U.K. model.

There are advantages to having a separate tribunal in terms of independence – an important value, as we all know and as the Ainsley judgment made clear. However, particularly in the context of a principles-based regulatory scheme, one would have to ensure that the “learning loop” remains vital.

Passport system versus national securities regulator

This report does not to try to answer the question of whether to proceed with a passport system or some form of single securities regulator. However, this question does affect implementation of a principles-based approach to regulation.

-

Concerns and possibilities in developing some form of principles-based national regulatory structure

For both the FSA and the European Union, the development of overarching principles was a pragmatic response to the challenges of trying to impose a regime on top of, or superceding, several pre-existing and different regimes. In the U.K., the prior regulators were amalgamated into the FSA. At the E.U., nation-state regulators continued to be the main law-developers, meaning that Union-level principles must still undergo a “translation” process into national law. [115] Creating a new, overarching regulator presents very real challenges but, if the E.U. experience is any guide, it may still be the simpler option.

Promulgating a principles-based model act at the national level does not by itself reduce the possibility of differences in application from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. [116] On the upside, this permits sensitivity to the uniqueness of different provinces. On the downside, the decision may be made that some of this uniqueness is not desirable. A model act that is implemented in substantially different ways across the country, by regulators that do not interact with each other closely, may mean that differences in enforcement priorities and regulatory expectations remain just as significant, but become less visible. In other words, legacy divergences in approach fall “under the radar,” and are expressed in implementation and enforcement practices rather than written law.

If coherence from jurisdiction to jurisdiction is a priority, some kind of communicative/oversight infrastructure is needed. This is especially true for a principles-based regulatory approach, because so much is left up to implementation. Implementing principles-based regulation consistently across Canada would put significant demands on communication structures between regulators, and would seem to require more regular and closer contact between regulators than the existing passport system permits.

-

Challenges and advantages to working with principles-based regulation within a passport system

When British Columbia started to consider its proposed more principles-based legislation, around 2004, there was concern about whether or not B.C. principles mapped onto more rule-based regimes elsewhere. Indeed, the desire to pursue harmonization was behind that province’s decision to put the legislation on hold.

Model acts have been used with substantial success in federal systems, as a way of ensuring some consistency between jurisdictions on matters that are within the jurisdiction of a subnational unit (e.g., provinces/territories, or states). The Uniform Commercial Code in the United States is a prominent example. In Europe, harmonization has taken place more through E.U. directives than model acts, though scholars have advocated for a model Company Law Act. [117] A principles-based model act would give provincial and territorial regulators a lodestar by which to orient their own practices, increasing harmonization and facilitating interprovincial mutual recognition.

Seen from another perspective, a principles-based model act could also reduce the pressure to harmonize distinct provincial regimes. It could create space for those regional differences that are significant in terms of recognizing each region’s uniqueness, but not significant to the degree that they adversely affect the regulation of Canadian capital markets. If each regulator is abiding by common principles, reinforced by meaningful enforcement and outcome-oriented measures of success, then some differences in approach, or methodology, between jurisdictions may become acceptable. [118] The overarching principles would give investors comfort about relying on Canadian oversight of capital markets, irrespective of local differences.