Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Creating an Advantage in Global Capital Markets

Objectives, Outcomes and

Performance Measures in Securities Regulation

A Research Study for the

Expert Panel on Securities Regulation in Canada

Larry P. Schwartz

Objectives, Outcomes and

Performance Measures in Securities Regulation

Biography

Larry P. Schwartz, Ph.D.

Larry Schwartz is an economist and consultant specializing in financial-sector policy and regulatory issues and competition policy. He prepared the paper on cost-benefit analysis for the recent Investment Dealers Association of Canada Task Force on the Modernization of Canadian Securities Legislation.

With previous experience in corporate lending and securities underwriting, he was a policy advisor in the Chair’s Office at the Ontario Securities Commission 1985-87, and has since consulted to Finance Canada (interdealer bond brokerage), the OSC (bought deals, soft-dollars), the Canadian Bankers Association, Bank-owned dealers (connected issuer rules), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada and The Toronto Stock Exchange. He participated in World Bank financial-sector development missions to Uganda, Tanzania and Pakistan.

As the full-time lay member of the federal Competition Tribunal 1998-2003, he adjudicated cases of merger and abuse of dominance under the Competition Act, and drafted the decision of the Tribunal in the landmark “Propane” merger case.

He teaches finance at the Schulich School of Business, York University and is a frequent writer and speaker on competition policy and capital markets issues. Mr. Schwartz earned the PhD, at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania and his B.A at the University of Toronto.

Executive Summary

The Expert Panel on Securities Regulation is charged with advising federal and provincial finance ministers on global best practices in securities regulation that advance the Government of Canada’s plan for capital markets as set out in “Creating a Canadian Advantage in Global Capital Markets”. This study for the Expert Panel concerns the development of a framework for establishing goals, objectives and performance measurement in securities regulation.

The approach taken here is to identify elements of a desirable framework and then to examine the practices of securities regulators in Canada and abroad and to suggest where these practices might be strengthened so as to advance the goals of securities regulation. By framework is meant the extent to which regulators articulate goals and objectives, measure their performance in achieving them, and disseminate their results. All securities regulators operate within such a framework to a greater or lesser extent.

The articulation of goals and objectives, whether in statute or in the regulator’s own statement of its mission, is important because, while capital markets have changed very dramatically in recent years, the traditional goals of securities regulation have become diffuse and perhaps outdated. Thus, the classic focus on investor protection is now commonly viewed through the lens of market efficiency and proportionate regulation even if the basic securities laws have not changed. In addition, there is increasing interest in how securities regulation interacts with other elements of economic policy and regional development. An important question arises whether regulation ought to be more directly concerned with financial system stability.

Correspondingly, there is a question about how regulators assess their performance. The literature suggests that regulatory bodies typically measure their performance with reference to activity levels. However, the framework concern is with “output”, the extent to which agencies are meeting and advancing their goals. This focus calls for the adoption of performance measures that are measurable and widely disseminated to policymakers, investors and the public at large.

The U.K. Financial Services Authority appears to be the leading financial regulator in terms of its fully-developed framework. As an integrated regulator with broad responsibility for the financial services sector, it has a statutory mandate that specifies market confidence, public awareness, consumer protection and the reduction of financial crime. It has also articulated “Principles of Good Regulation” that include economic efficiency, proportionality of restrictions on industry, and competition within the sector, inter alia.

To measure its attainment of these goals and objectives, FSA measures its performance in three areas: promoting efficient markets, helping consumers to get a fair deal, and improving its internal effectiveness. In its annual “Performance Account”, FSA reports various measures of the extent of its performance in these areas. FSA has also developed 64 service standards and provides statistical account of its progress in meeting those standards.

A similar, but less well-developed approach has been adopted by the Australian Securities Commission, largely in response to government policy which seeks to improve the governance, transparency and accountability of independent agencies and to attain better balance between market efficiency and investor protection. Accordingly, the Commission has instituted service standards and identified key performance indicators, the latter appearing to focus on activity levels and input measures. It is also apparent that there is some conflict between the regulator and the government on fundamental issues of goals and performance measurement.

In Canada, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions faces specific Treasury Board reporting requirements as well as a modern statutory framework that recognizes the benefits of competition and risk-taking among regulated financial institutions. OSFI measures its effectiveness by means of regular surveys, but in other respects it is required to report progress against implementation priorities. Thus, it reports on the extent to which it has acquired the identified input capacity (i.e. in order to better assess risk) rather than the output capacity itself (measures of risk). Performance measurement within OSFI is conceptually difficult because its statute makes clear that its performance is not to be assessed in light of financial institution failure.

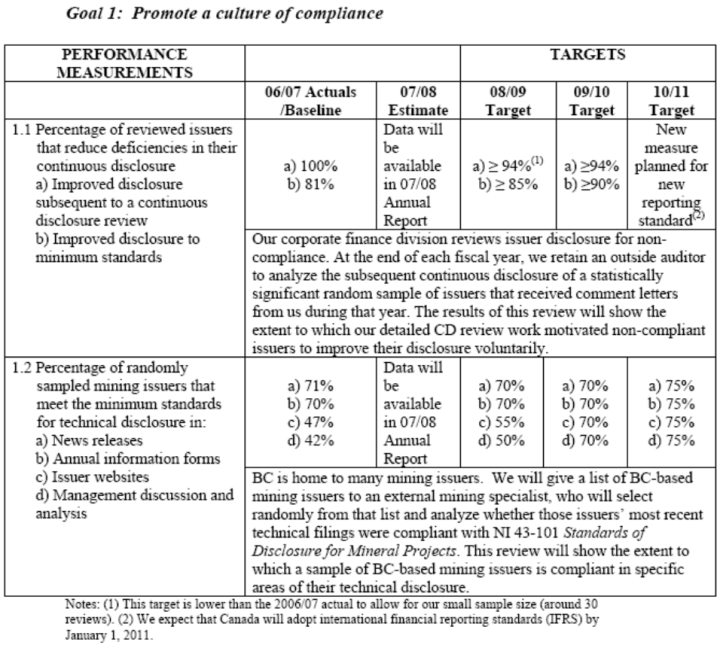

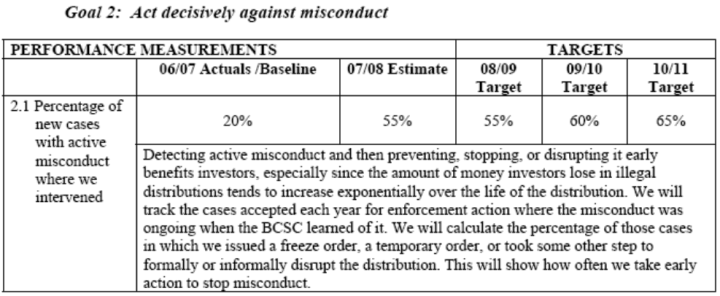

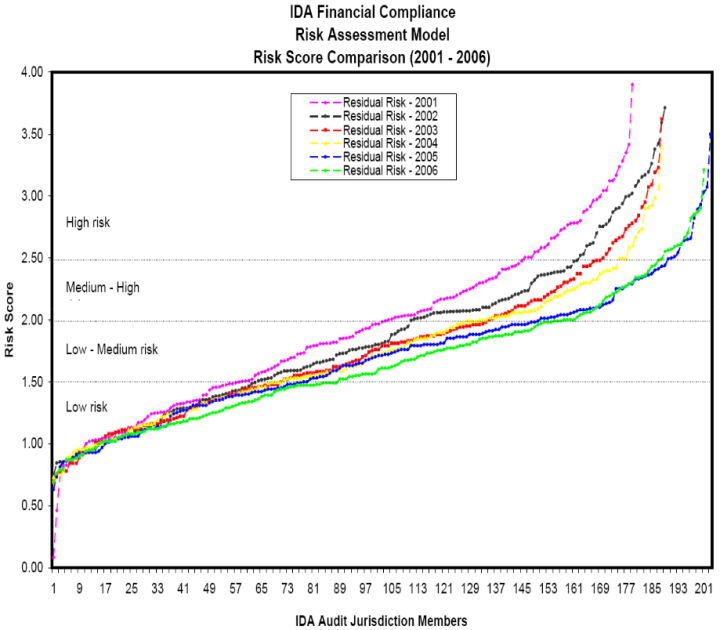

Among the three provincial securities regulators studied, the British Columbia Securities Commission has established the most comprehensive framework of performance measurement. Although recently instituted, it specifies clear goals and objectives and seeks to identify quantifiable measures of the results of its regulatory interventions.

The statutory framework in Ontario is specific, not only with respect to fundamental goals (investor protection, market efficiency), but also regarding principles including proportionate regulation. It is the only province with cost-benefit analysis requirements in rule-making. However, its performance measurement is quite limited.

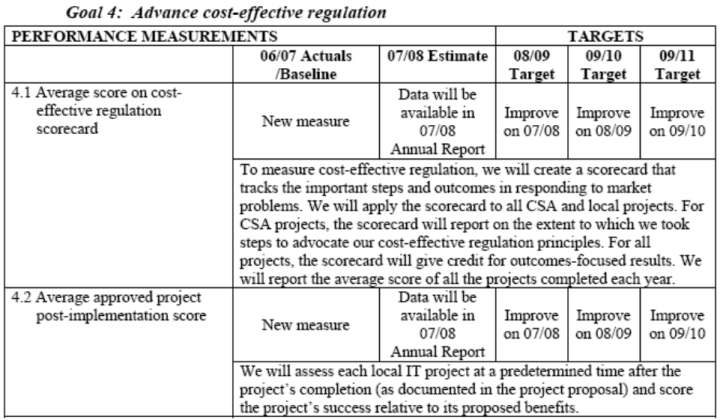

The Québec regulator is responsible for securities, insurance, non-bank deposit-taking institutions and market intermediaries generally. It has undertaken enhanced monitoring in support of the detailed statutory expression of goals and objectives, but it tends to measure its level of activity (e.g. number of inspections and investigations) rather than the extent to which progress toward the attainment of those goals and objectives has been achieved. The Investment Industry Regulatory Organization, the self-regulatory body takes the same approach, although its measure of industry risk is an output measure.

The IOSCO framework is somewhat narrow when compared with the various goals pursued by Canadian securities regulators who, by and large, do not accord its focus on investor protection the same priority. However, none of the Canadian regulators have adopted the goal of financial system stability that is one of IOSCO’s three “core principles”.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: U.K. Financial Services Authority

- Chapter 2: Australian Securities and Investment Commission

- Chapter 3: Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions

- Chapter 4: Ontario Securities Commission

- Chapter 5: Québec Autorité des Marchés Financiers

- Chapter 6: British Columbia Securities Commission

- Chapter 7: Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada

- Chapter 8: Elements of a Framework for a Common Securities Policy

- Bibliography

Introduction

The Expert Panel on Securities Regulation is charged with advising federal and provincial finance ministers on global best practices that advance the Government of Canada’s plan for capital markets as set out in “Creating a Canadian Advantage in Global Capital Markets”.

Among the areas of the Expert Panel’s review and advice are the objectives, outcomes and performance measures that will best anchor securities regulation and the pursuit of a Canadian advantage in global capital markets. These may include

- Efficient and competitive capital markets that contribute to economic growth and prosperity

- Market integrity and the protection of investors

- The reduction of systemic risk

To assist the Expert Panel in this part of its mandate, this report examines the goals of securities regulation in Canada and abroad and the adoption of performance standards and measurement systems by securities regulators in order to identify a framework in which global best practices and opportunities to create a Canadian advantage can be identified.

1. Goals and Objectives: Why are they important?

It is apparent that securities market activity has grown significantly in all of the developed and emerging economies. This growth stems from fundamental changes in technology and in society at large and is reflected in the disintermediation of savings through traditional financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies.

For many years now, individual investors have been accessing capital markets directly through brokers and dealers and portfolio managers including mutual funds and (defined contribution) pension funds, rather than putting their savings in bank accounts or insurance policies to be invested by the financial intermediaries for their own, rather than for the individuals’, accounts. Correspondingly, businesses have turned increasingly to short-term commercial paper and medium and long-term bond markets in preference to banks to fund their operations.

These well-established shifts in market activity have resulted from growing economic efficiencies brought about through communications and computer technology that allow the very rapid dissemination of information and transaction-processing. Indeed, innovation within securities markets has been very dramatic as witnessed, for example, by the development of alternative trading systems that have arisen to challenge the dominance of the traditional stock exchange.

However, the regulatory environments have been slower to change. Many of the goals and objectives that currently drive securities regulation were established in response to the Great Crash in 1929 which gave rise to the creation in the 1930’s of the United States Securities and Exchange Commission and the Ontario Securities Commission. Thus, as late as the 1990’s, Instinet Corp. was denied a license to operate in Ontario because the Commission felt that the public interest required it to “protect” the Toronto Stock Exchange from competition from new trading technologies.

Accordingly, new financial services, products and technologies face a regulatory regime that retains some of the foci and constraints that were instituted decades ago. Of course, securities regulators are well-aware of these developments but they are required to view them through the lens of statutes and regulatory history that emphasize the goals and objectives of earlier periods. As securities regulation in the various jurisdictions modernizes slowly, it is not surprising that some regimes secure the economic advantages of efficiency and innovation earlier than others.

The study begins with the premise that the statutory provisions that guide securities regulation are important even if they express general statements of purpose or intent. However, securities laws in several provinces are silent with respect to goals and objectives. To determine what path the regulator is following, it will be necessary to consult other sources of information, such as the regulator’s own description of its mission. Indeed, even when the statutory regime indicates goals and objectives, the discretion granted to securities regulators means that the statutory framework may not be the sole source of information.

2. Principles for Performance Measurement

The mere adoption of modern goals and objectives in securities regulation would be insufficient. Even when accepted as legitimate, a goal (such as “enhanced investor protection” or “capital market efficiency”) may be expressed at a very high level of generality and, despite high levels of activity directed towards its attainment, it may be unclear whether the goal is achieved or not.

The OECD observes that, traditionally,

regulatory agencies’ performance and cost-effectiveness are managed and evaluated largely by reference to their level of activity, rather than the outcomes they accomplish. Valid measures of compliance rates and outcomes will give governments the capacity to evaluate regulatory agency performance by outcomes ( vis-à-vis cost and activity), and to target agency resources towards where they are likely to be most effective. [1]

Effective securities regulation requires some form of performance measurement that goes beyond activity levels. Policymakers, the public and regulators themselves would like to know to what extent the interventions are achieving the accepted goals and objectives.

Thus, while performance measurement is desirable, it is often difficult to put into practice. Often the goals do not lend themselves to measurement; there is, for example, no single index of market efficiency that might be consulted. Where measures are available, they may be uninformative, as the OECD notes with respect to activity levels.

The following questions suggest generic principles that might be used, inter alia, to evaluate the success of the regulatory process:

-

Is the regulator adopting the least-costly approach?

-

Does the regulator consider alternate means of achieving the objective?

-

Is the impact of the regulatory intervention measurable?

-

When the regulator evaluates its performance, does it measure inputs (such as activity levels) or outputs?

-

Is the performance measure by which the regulation is evaluated disclosed publicly?

-

Does the problem at hand require direct regulatory intervention, or might it be resolved by the market? (i.e. regulate only where demonstrably needed?)

-

Is there accountability and transparency in decision-making? (Is someone held accountable for achieving the desired outcome? Are there rewards for achieving and consequences for failure?)

-

Does the public understand what the regulator is doing in clear terms?

-

Do the regulated firm and personnel understand what the regulator is doing in clear terms?

-

Are rules applied consistently across the country?

-

Are the direct and indirect costs of regulation roughly similar to those in other jurisdictions?

Accordingly, this study will examine the goals and objectives adopted by securities and financial regulators in Canada and abroad, and will attempt to ascertain what principles and measurement efforts are guiding their efforts.

3. Elements of a Framework

A framework begins with an articulation of the goal or goals of securities regulation. These goals, such as investor protection, are typically stated at a high level of generality and reflect the common understanding of why the proposed regulatory regime is necessary.

To meet these goals, securities regulators must propose specific objectives in the form of regulations or rule changes. Thus, under the goal of protecting investors, the regulator might propose to improve the disclosure of financial information by issuers. This objective gives specific content to the goal assigned to the regulator.

After implementing the rule-change, the regulator seeks, whether formally or informally, to evaluate its impact on investor protection. This evaluation requires the regulator to identify the relevant measure of performance. For example, the regulator might evaluate the effectiveness of the rule-change by the change in the number of complaints it receives from the investing public. This measure may not be unique; indeed it may not be a particularly good measure, but it has the desirable property that it is attainable at low cost.

Having collected the appropriate performance data and drawn conclusions about the effectiveness of the rule-change, the regulator then decides whether to publish the number of complaints of inadequate disclosure on a regular basis.

These steps constitute a complete framework of performance measurement. At any given time, the securities regulatory body has such a system in place, even if the data collection is perhaps anecdotal, the performance measure(s) not completely informative, and the dissemination of results limited.

As the regulator identifies objectives over time, it may become apparent that other, perhaps previously unstated, goals are also important. While the objective of improved financial disclosure is undoubted, the rule-change may impose significant costs of compliance on issuers that the regulator also takes seriously. Thus, it may be modified in light of the goal of “proportionate regulation” that the securities regulator has been mandated to consider, and new measures of performance will be required.

Thus, the framework becomes somewhat complex. Relevant goals may not be the ones in the statute; objectives may be limited by implicit goals, and performance measurement may be difficult to design and costly to assess. Nevertheless, all regulatory agencies have an understanding of the framework under which they operate; opportunities for improving the framework can be gleaned from observing how the agencies fulfill their mission.

4. Organization of the Report

The first part of the report reviews and documents the statutory goals and objectives and related performance standards and measurement efforts by the U.K.’s Financial Services Authority and Australia’s Securities and Investment Commission. The FSA has gone the furthest in defining and implementing formal performance measurement systems.

The second part of the report reviews and documents goals, objectives and performance measurement by Canada’s Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions. As part of the federal government, this agency has extensive reporting requirements that include performance measurement.

The third part of the report presents information on provincial securities regulators’ goals in, Ontario and Quebec, and British Columbia and attempts to determine how well they achieve them. What performance measures do they use? Do they have systems that accurately measure their progress? How do their efforts compare with other jurisdictions? As markets have evolved, are there gaps in their mandates?

The final section of the report contains suggestions for the framework for performance measurement, including goals, objectives and performance indicators that securities regulation should target.

Chapter 1

U.K. Financial Services Authority

1. General

The Financial Services Authority (“FSA”) is the main regulator for the UK financial services industry, covering both prudential and conduct-of-business regulation for banking, insurance and securities. An independent non-governmental body, its statutory powers are given by the Financial Services and Markets Act, 2000 (the “2000 Act”). The statutory goals of FSA and the detailed specification of performance standards and measurement processes make it a good model for other regulators.

2. Statutory Mandate

The 2000 Act sets out four statutory objectives that are supported by a set of principles of good regulation to which the FSA must have regard when discharging its functions.

-

Statutory objectives:

-

Market confidence: maintaining confidence in the financial system

-

Public Awareness: promoting public understanding of the financial system

-

Consumer protection: securing the appropriate degree of protection for consumers; and

-

The reduction of financial crime: reducing the extent to which it is possible for a business to be used for a purpose connected with financial crime.

-

-

Principles of Good Regulation

Further to section 2(3) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, the FSA has enunciated certain principles to which it has regard in fulfilling its statutory mandate. These principles form the core of the FSA’s approach to implementing principles-based regulation:

-

Efficiency and economy: the need to use resources in the most efficient and economic way .

The non-executive committee of the Board is required to oversee the allocation of resources and report to the Treasury every year. The Treasury is able to commission value-for-money reviews of our operations.

-

Role of management: the responsibilities of those who manage the affairs of authorized persons .

A regulated firm’s senior management is responsible for its activities and for ensuring that its business complies with regulatory requirements. This principle is designed to guard against unnecessary intrusion by the regulator into firms’ business and requires FSA to hold senior management responsible for risk management and controls within firms.

-

Proportionality: The restrictions that FSA imposes on industry must be proportionate to the benefits that are expected to result from those restrictions.

In making judgments in this area, FSA takes into account the costs to firms and consumers. One of the main techniques is cost-benefit analysis of proposed regulatory requirements. This approach is shown in the different regulatory requirements that apply to wholesale and retail markets.

-

Innovation: the desirability of facilitating innovation in connection with regulated activities.

This involves allowing scope for different means of compliance so as not to unduly restrict market participants from launching new financial products and services

-

International character: the international character of financial services and markets and the desirability of maintaining the competitive position of the UK.

The FSA takes into account the international aspects of much financial business and the competitive position of the UK. This involves co-operating with overbears regulators, both to agree international standards and to monitor global firms and markets effectively.

-

Competition: the need to minimize the adverse effects on competition that may arise from FSA activities and the desirability of facilitating competition between the firms it regulates.

These principles cover avoiding unnecessary regulatory barriers to entry or business expansion. Competition and innovation considerations play a key role in the FSA’s cost-benefit analysis work. Under the 2000 Act, the Treasury, the Office of Fair Trading and the Competition Commission review the impact of FSA rules and practices on competition.

3. Performance Standards

Having regard to the statutory framework and the detailed principles of good regulation, the FSA describes its general mandate under three strategic aims:

- Promoting efficient, orderly and fair markets;

- Helping retail consumers achieve a fair deal; and

- Improving its business capability and effectiveness

The FSA has established the Performance Account through which it provides stakeholders with detailed information about its performance. The Performance Account sets out how FSA measures its performance against its strategic aims.

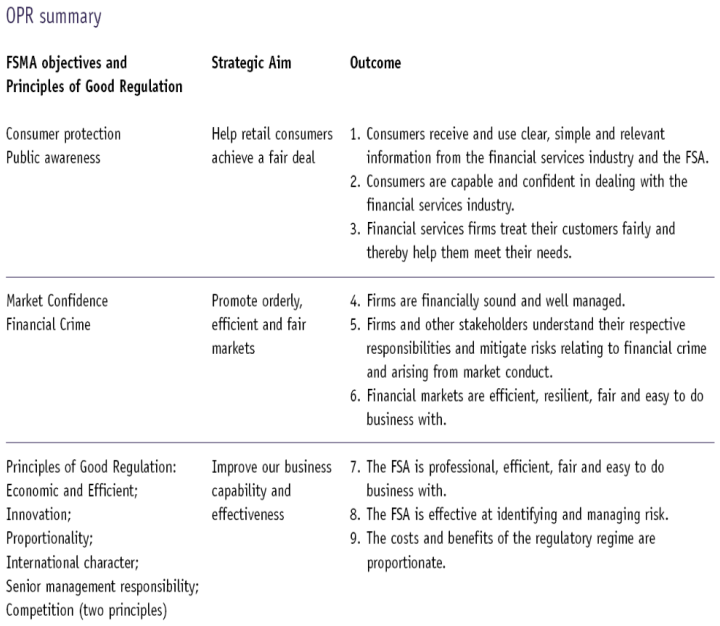

In 2007, FSA published the Outcomes Performance Report that clearly aligns the objectives and regulatory principles in the 2000 Act with its strategic aims. As shown in Exhibit 1-1, three outcomes are linked to each of the three aims. The Outcomes Performance Report is a key tool in the FSA’s drive to become more outcome-focused and principles-based.

The FSA intends that each outcome be tracked and measured on a regular basis, recognizing that some outcomes will be difficult to measure. The indicated outcomes in Exhibit 1-1 will be assessed as follows:

-

Consumers receive and use clear, simple and relevant information from the industry and from FSA

To be assessed using the Consumer Outcome Study (first report Autumn 2007)

-

Consumers are capable and confident in exercising responsibility when dealing with the financial services industry

A long-term outcome, assessed by means of the Financial Capability Survey every four to five years

-

Financial services firms treat their customers fairly and so help them to meet their needs

Addresses whether firms treat their customers fairly and whether consumers end up with suitable financial products and services. Tracked through the ARROW supervision framework, complaints data, thematic work (i.e. special studies), performance against Treating Customer Fairly (“TCF”) embedding and other inputs described in the annual TCF performance report (first published November 2007)

-

Firms are financially sound and well managed

Assessed by ARROW risk assessment and the internal Alert and Risk Indicator to understand financial soundness and management of smaller firms; informed by regulatory returns

-

Firms and other stakeholders understand their respective responsibilities and mitigate risks relating to financial crime and arising from market conduct

This is assessed using the Financial Crime Survey of firms, the Consumer Awareness Survey, and market cleanliness measures. Market cleanliness is reflected in the extent to which ‘informed price movements’ are observed ahead of significant regulatory announcements by issuers.

-

Financial markets are efficient, resilient and internationally attractive

Efficiency is measured through a series of wholesale and retail measures and the efficiency of the UK Listing Authority. Resilience is measured through the Resilience Benchmarking Project. International attractiveness is gauged through a number of surveys assessing London’s relative position as an international financial centre and through its share of financial activities such as initial public offerings.

-

The FSA is professional, fair, efficient and easy to do business with

Assessed by the two-yearly Practitioner Panel survey, external Service Standards, and internal customer satisfaction surveys of regulatory processes. Fairness tracked by feedback in the Enforcement Performance Account.

-

The FSA is effective in identifying and managing risks to its statutory objectives

Based on survey of what relationship-managed firms think about FSA supervision

-

The costs and benefits of regulation are proportionate

The “Cost of Regulation” study with Deloitte and the “Administrative Burdens” report have provided details on where FSA should focus its efforts to reduce costs. FSA is looking at more studies to improve its ability to track cost, benefit and proportionality

Two areas of the Performance Account that have been subject to well-defined statistical measurement are Service Standards and Enforcement Performance.

4. Service Standards

The Performance Account includes reports on FSA’s performance in meeting service standards that it has adopted. Most standards are voluntary commitments (e.g. dealing with inquiries from the public) but others are statutory deadlines (e.g. filing deadlines) that apply to all applications.

Standards have been established in the following service areas [2] :

-

Authorization (licensing/registration)

e.g. A1.1 to process 100% of complete applications for corporate authorization within 6 or 12 months of receipt; 75% within 3 months of receipt -

Regulatory decisions

e.g. R2.1 to consider 100% of notices of a proposed alteration to a Collective Investment Scheme and, if appropriate, issue a warning notice, within 1 month -

Complaints about the FSA

e.g. C1.2 Stage 1: to acknowledge 100% of complaints and send a leaflet explaining how the Complaints Scheme works and the right to ask for a stage two investigation, within 5 working days -

Listing

e.g. L1.1 to process 100% of applications for listing within 6 months of receipt -

Notifications

e.g. N1.1 to process 100% of complete notifications for Appointed Representative status within 5 working days of receipt -

Communications

e.g. CM1.1 to provide a substantive response to 90% of letters, emails, or faxes received by the Firm Contact Centre, FSA Relationship Manager, or relating to certain types of questions about fees, within 12 working days of receipt

The list of current standards is provided in Exhibit 1-2.

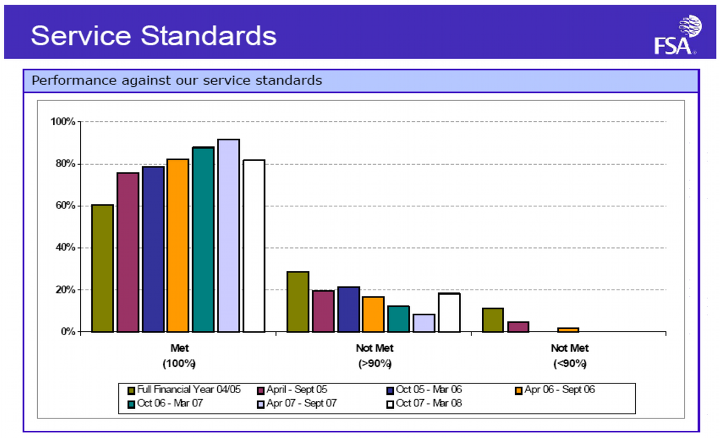

The Performance Account reviews the 64 service standards that were in place between October 1, 2007 and March 31, 2008. [3] During this time, there were no transactions for four of the 64 standards.

For the 60 standards where transactions did occur, FSA met 49 (or 81.7%) and did not meet 11 (18.3%). FSA notes that of the eleven unmet standards, nine have targets of 100% meaning that a delay in any single case may result in a missed standard. FSA also notes that its performance was over 96% in such standards.

Exhibit 1-3 shows FSA’s performance against prevailing service standards over the last four years. Note that because new standards are introduced and some are deleted over time, the year-to-year results are not completely comparable. The results in the latest reporting period, October 2007 to March 2008, show a decrease in performance compared to the previous period. However, there were no missed standards below 90% of the target.

FSA makes clear that, given a choice between meeting a standard and taking more time to make the right decision, it will take more time.

5. Enforcement Performance Account

FSA considers the effectiveness of enforcement on a regular basis through measurement and reporting on performance. It produces an annual performance account of the fairness and effectiveness of its enforcement activity and publishes statistics thereon in its annual report.

FSA views enforcement action as one of several instruments that it can use in achieving its statutory objectives:

Our approach is to achieve credible deterrence through our enforcement work. We focus on those cases where we think we can make a real difference to consumers and markets, using enforcement strategically as a tool to change behaviour in the industry. To achieve credible deterrence, wrongdoers must realise that they face a real and tangible risk of being held to account and expect a significant penalty. This applies across the spectrum, from our work to prevent market abuse, to our work helping to ensure that customers are treated fairly. [4]

FSA brings enforcement actions on violations of both its Principles and its rules, the former having the status of the latter. FSA views its enforcement policy as an important component in its move toward principles-based regulation:

Most enforcement actions in the last financial year were based on Principles only or a combination of Principles and rules. Of 48 disciplinary cases, 21 (44%) were based on Principles and almost all of the remaining cases were a combination of Principles and rules. This demonstrates the continued alignment of enforcement with the move towards principles-based regulation. Our Principles have the status of rules and we will continue to take action where they are breached. Our new Enforcement Guide, which was adopted on 28 August 2007, makes clear that we acknowledge that firms may comply with the Principles in different ways and that we will not take enforcement action unless it was possible to determine at the relevant time that the conduct fell short of our requirements. We will apply the standards required by the Principles at the time the conduct took place and not later, higher standards. However, where conduct falls below the standards we require, we may take action even if the conduct is widespread within the industry. [5]

The FSA’s statistical report on enforcement activities for the period 2007/08 is contained in its annual report. [6]

In light of FSA’s approach to enforcement, it is apparent that the statistics must be placed in context. Since, as FSA indicates, enforcement is a relatively small part of its work, a high number of cases opened need not be a good indicator of its effectiveness.

6. General Observations

It is apparent that FSA has devoted considerable effort to translating its statutory directives into clearly-articulated operational objectives, strategic aims and outcomes. In addition, it has established a measurement system that enables it to assess the extent to which it has attained those outcomes.

As to goals and objectives, it is noteworthy that the traditional goal of “investor protection” is discussed in terms that are concrete: clear information provided to customers, confident customer capability, and fair treatment by firms. This attempt to “flesh out” what it means by investor protection may be a reaction to the tendency to justify all regulatory interventions on the basis of an ill-defined objective that, once invoked, cannot be challenged.

It is also noteworthy that the FSA’s “economic” objectives give effect, not only to the statutory objective of efficient markets, but also to competitive conditions in financial services. FSA clearly seeks to maintain London’s pre-eminent position as an international financial centre, even though it faces no explicit statutory requirement to do so. This concern with industry competitiveness is expressed in terms of “proportionate regulation”, service standards, and keeping U.K. markets “internationally attractive”. The significance of its competitiveness objective may be the reason why FSA has devoted so much effort to cost-benefit analysis in analyzing proposed regulatory interventions.

These broader economic objectives are likely related to the growth of the financial services sector in the European Union and to the competitive efforts among the Member States to attract companies to their own financial centres. In this regard, it should also be noted that as an integrated regulator, FSA is attractive to foreign firms operating in different financial industries. Such firms will face one regulator with similar policy objectives across the financial services that it regulates.

It may also be noted that neither FSA’s statute nor its various interpretations thereof make reference to international financial market stability. This omission is surprising in light of London’s stature as an international financial centre, and may result from the fact that FSA is a non-governmental body. Thus, there may be an implicit understanding that financial stability issues are beyond its capability to influence, and fall within the domains of the Bank of England and the Treasury.

From a measurement perspective, FSA accepts that its performance should be based on outputs that are measurable. While it maintains and reports statistics on its activities, these statistics relate less directly to its statutory and self-imposed goals and objectives.

It is also noteworthy that FSA publishes its performance measures. The “Performance Account” appears to be a unique development.

Although measurement is a clear concern for FSA, it is interesting that it makes use mainly of surveys. Apparently, FSA does not assess economic objectives directly. For example, one might have thought that FSA would undertake regular studies of the extent to which stock prices reflect publicly available information. Such information could be extremely valuable in assessing concerns about capital market efficiency, “insider information” and discounts on initial public offerings.

Similarly, FSA does not explicitly report on the success of its efforts to enhance the international competitiveness of the London market. However, this may reflect a political sensitivity within the European Union.

It may also be pointed out that the FSA’s efforts in performance measurement appear to require a significant budgetary expense and claim on management time and resources.

Exhibit 1-1: Operational Performance Report

Exhibit 1-2: Current Performance Standards

We are constantly seeking to improve our performance so our service standards are regularly reviewed to ensure they are appropriate and challenging.

List of current standards

The following table lists all of the service standards that apply from 1 April 2008.

For a more detailed explanation of what a given standard means, click on its ID.

|

Authorisation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Standard |

Target |

|||

|

To process a complete application for corporate authorisation |

100% within 6 or 12 months of receipt |

|||

|

75% within 3 months of receipt |

||||

|

To process Money Laundering registrations (2) |

100% within 45 days of receipt of application or receipt of any further required information |

|||

|

To process applications for the authorisation of new schemes under section 242 for Authorised Unit Trusts (AUT) and Regulation 12 for Open Ended Investment Companies (OEIC) (1) |

100% within the earlier of 12 months from receipt or 6 months from being deemed complete |

|||

|

To process applications under s242 for the authorisation of Unit Trust Schemes and under Regulation 12 of The Open Ended Investment Companies Regulations 2001 for authorisation of an OEIC |

75% within 6 weeks of receipt |

|||

|

To consider whether an EEA UCITS scheme that has given a notice to the FSA of its intention to invite UK persons to invest will be compliant with UK law and, where not, to issue a notice to that effect |

100% within 2 months of receipt |

|||

|

To consider notifications for recognition from schemes authorised in Table 5-2 (con’t) designated countries or territories and, if appropriate, issue a warning notice |

100% within 2 months of receipt |

|||

|

To process a complete registration application from a Mutual Society |

90% within 15 working days of receipt |

|||

|

Regulatory decisions |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Standard |

Target |

|

|

To process an application for approved person status |

100% within 3 months of receipt unless attached to an application for Part IV Permission |

|

|

85% within 2, 4 or 7 working days |

||

|

To consider notice of a proposed alteration to a Collective Investment Scheme and, if appropriate, issue a warning notice |

100% within 1 month |

|

|

To process an application from an authorised firm for Variation of Permission |

100% within 6 months of becoming complete or 12 months of receipt |

|

|

To process a complete application from an authorised firm for Variation of Permission |

70% within 2 months of application becoming complete |

|

|

To make a decision following receipt of a 'valid' notification to approve a change in control |

100% within 3 months of receipt |

|

|

To give waiver decisions for an application which includes sufficient information |

90% within 20 working days of receipt |

|

|

To determine applications for Cancellation of Part IV Permission |

100% within the earlier of 1) 6 months of application becoming complete (if an application is received complete) or 2) 12 months of the application first being received by the FSA |

|

|

80% within 3 months of receipt (2) |

||

|

To respond to requests from EEA or Swiss regulators in respect of insurance business transfers outside the UK |

100% within 3 months of receipt |

|

|

To consent to, or refuse, changes to branch details for a branch established by a UK firm exercising its EEA rights |

100% within 1 month of notification |

|

|

To consent to, or refuse, changes to relevant details for a UK firm which is providing services in exercise of an EEA right |

100% within 1 month of notification |

|

|

Complaints about the FSA |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Standard |

Target |

|

|

Fast Track: To complete the investigation and respond to the complainant and send a leaflet explaining how the Complaints Scheme works and the right to ask for a stage one investigation |

100% within 5 working days |

|

|

Stage 1: To acknowledge a complaint and send a leaflet explaining how the Complaints Scheme works and the right to ask for a stage two investigation |

100% within 5 working days |

|

|

Stage 1: To notify the complainant if the complaint will not be admitted to the Scheme at stage one |

100% within 4 weeks |

|

|

Complete a stage one investigation and write to the complainant with results of the complaint or write to the complainant to set out a reasonable timescale within which the FSA plans to deal with the complaint |

100% within 4 weeks |

|

|

Listing |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Standard |

Target |

|

|

To process an application for listing |

100% within 6 months of receipt |

|

|

To comment on the initial proof of a document submitted for pre-vetting by a new applicant for listing |

95% within 10 days of receipt |

|

|

100% within 10 days of receipt |

||

|

To comment on the initial proof of a document submitted for pre-vetting by an issuer already listed |

95% within 5 days of receipt |

|

|

100% within 5 days of receipt |

||

|

To comment on subsequent proofs of documents submitted for pre-vetting |

95% within 5 days of receipt |

|

|

100% within 5 days of receipt |

||

|

To reply to a complaint about a listed company |

95% within 5 working days of receipt |

|

|

100% within 5 working days of receipt |

||

|

Notifications |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Standard |

Target |

|

|

To process a complete notification for Appointed Representative status |

100% within 5 working days of receipt |

|

|

To process a complete post-event notification to change the FSA's static data on a regulated firm |

95% within 5 working days of receipt |

|

|

To process a complete pre-event notification to change the FSA's static data on a regulated firm |

95% on or before the date requested by the firm |

|

|

To notify the firm of the applicable provisions if they are an EEA firm wanting to establish a branch in the UK |

100% within 2 months of receipt |

|

|

To notify the firm of the applicable provisions if they are an EEA firm wanting to provide services in the UK |

100% within 2 months of receipt |

|

|

To inform the firm if a consent notice will not be issued for a UK firm wanting to establish a branch in the EEA |

100% within 3 months of receipt |

|

|

To provide a copy of the notice of intention to the host state regulator if a UK firm expresses the intention to provide cross-border services in an EEA country |

100% within 1 month |

|

|

Communications |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Standard |

Target |

|

|

To provide a substantive response to letters, emails or faxes received by the Firm Contact Centre, FSA Relationship Manager, or relating to certain types of questions about fees |

90% within 12 working days of receipt |

|

|

To provide a draft letter of our findings and recommendations following an "ARROW" discovery visit to a firm |

70% within 10 weeks for a Full ARROW assessment/Light ARROW plus Capital assessment or 6 weeks for a Light ARROW assessment |

|

|

To provide a substantive response to correspondence received by the Consumer Contact Centre |

90% within 12 working days of receipt |

|

|

To meet requests received through the automated consumer leaflet request telephone lines |

95% within 5 working days of receipt |

|

|

The telephone call abandonment rate for calls made directly to the Consumer Contact Centre |

Not more than 5% |

|

|

To answer telephone calls made directly to the Consumer Contact Centre |

80% within 20 seconds |

|

|

The telephone call abandonment rate for calls made directly to the Firm Contact Centre |

Not more than 5% |

|

|

To answer telephone calls made directly to the Firm Contact Centre |

80% within 20 seconds |

|

|

To process simple oral queries relating to the Code of Market Conduct |

90% within 24 hours |

|

|

To process complex queries relating to the Code of Market Conduct |

100% within a timeframe consistent with the enquirer's requirements |

|

|

To consult on relevant documentation |

To inform the industry in 100% of cases where the consultation period is less than 3 months |

|

|

To provide a substantive reply to MPs' letters |

80% within 30 working days |

|

|

100% within 60 working days |

||

|

To reply to 'right to know' requests for information made under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 |

100% within 20 working days of receipt (unless public interest extension applies) |

|

|

To reply to requests for information made under the Data Protection Act 1998 |

100% within 40 working days of receipt |

|

|

To pay correct invoices received from suppliers |

90% within 30 working days of receipt of a correct invoice |

|

|

To ensure availability of customer facing IS systems (2) |

98.5% availability of the systems (currently measured Monday to Friday, 7am to 8pm, UK time) |

|

(1) This is a new definition that came into effect on 1 April 2008.

(2) This is a new standard that came into effect on 1 April 2008.

© Financial Services Authority | Page last updated 30/04/08

Exhibit 1-3: Service Performance over Time

Chapter 2 Australian Securities and Investment Commission

1. General

The experience with goal, objectives and performance measurement in Australia is of interest to Canada because of similarities in the economies of the two countries, the federal structure, and the concern with economic aspects of securities regulation.

In addition, the Australian situation may be of interest because the national securities regulator began operating in 1991, replacing the National Companies and Securities Commission (NCSC) and the Corporate Affairs offices of the states and territories.

The Australian Securities and Investment Commission (“ASIC”), established on 1 July 1998, is now an integrated regulator, responsible for consumer protection in superannuation, insurance, deposit taking and credit, resulting from the recommendations of the Financial System Inquiry. The Inquiry had found that financial system regulation was piecemeal and varied, and was determined according to the particular industry and the product being provided. This was seen as inefficient, as giving rise to opportunities for regulatory arbitrage, and in some cases leading to regulatory overlap and confusion.

However, there has been some tension over basic goals and objectives of securities regulation between the ASIC and the government.

2. Statutory Mandate

The responsibilities of ASIC in performing its functions and exercising its powers are set out in the ASIC Act (2001) [7] , which provides that ASIC must “strive” to:

-

Maintain, facilitate and improve the performance of the financial system and the entities within that system in the interests of commercial certainty, reducing business costs, and the efficiency and development of the economy; and,

-

Promote the confident and informed participation of investors and consumers in the financial system, and

-

Administer the laws that confer functions and powers on it effectively and with a minimum of procedural requirements, and

-

Receive, process and store, efficiently and quickly, the information given to ASIC under the laws that confer functions and powers on it; and

-

Ensure that information is available as soon as practicable for access by the public; and

-

Take whatever action it can take, and is necessary, in order to enforce and give effect to the laws of the Commonwealth that confer functions and powers on it.

It is noteworthy that the statutory objects of the ASIC give prominence to the economic objectives relating to financial system performance, reducing regulatory burden, and economic efficiency and development.

The second statutory object addresses the investor protection objective, but is limited to promoting participation by confident and informed investors.

3. Service Standards

The ASIC Service Charter sets out how the ASIC serves its clientele, what they can expect and how they may facilitate ASIC assistance in all matters save surveillance and enforcement.

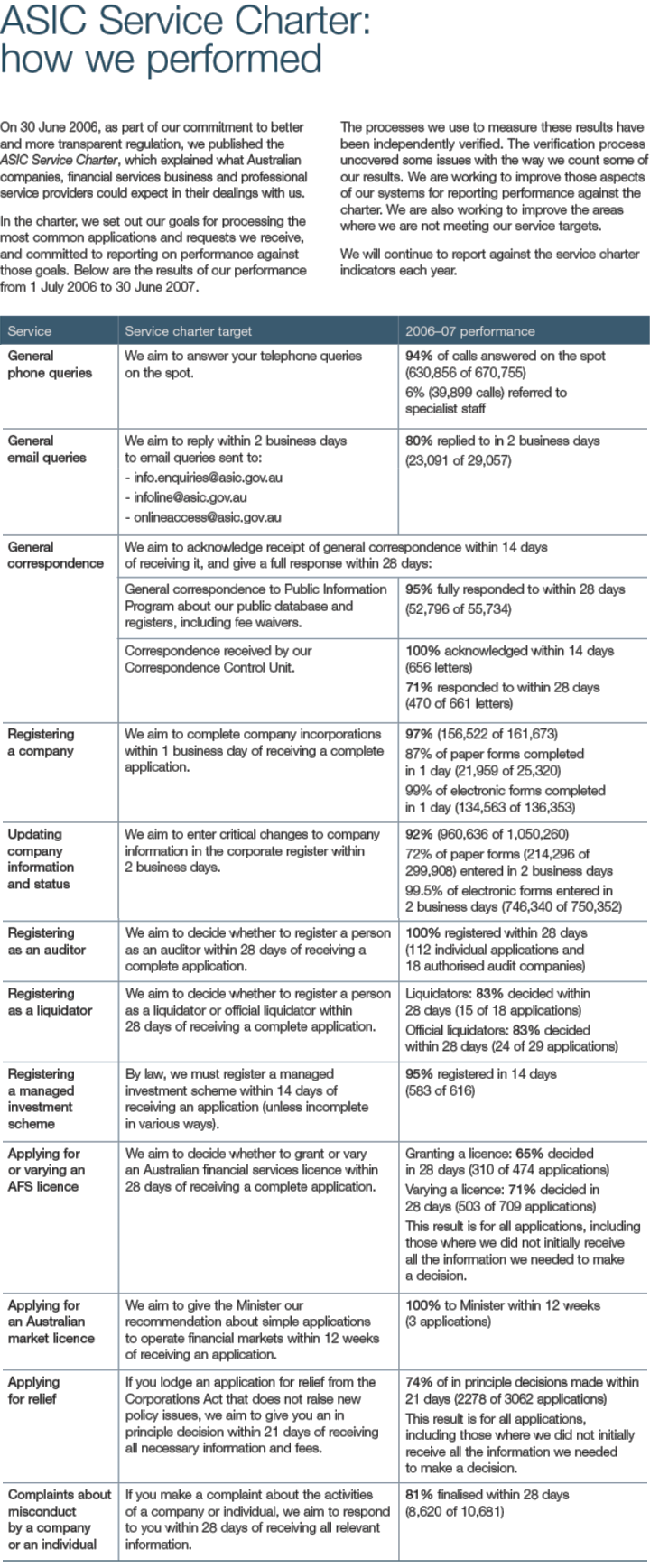

Exhibit 2-1 identifies the various service dimensions for handling inquiries from the public, the goal for response time to each, and its record of meeting these services goals in the fiscal year 2006-2007.

4. Key Performance Indicators

On February 20, 2007, the Treasurer issued the Government’s Statement of Expectations for the ASIC. The Statement results from a recommendation in the Review of Corporate Governance of Statutory Authorities and Office Holders that identified ways in which the governance of Commonwealth “portfolio bodies” may be improved, transparency and accountability increased, and clear relationships between different arms of Government be established.

The Government’s Statement also forms part of the response to the Report of the Taskforce on Reducing Regulatory Burden on Business. That Report proposed that the Government provide specific guidance to ASIC about the appropriate balance between pursuing safety and investor protection, and market efficiency. As a result of the Report’s recommendations, the Treasurer proposed that ASIC develop, inter alia, principles-based regulation, produce key performance indicators, pay greater attention to Government policy directions and objectives, and cooperate with other economic regulators.

The development of key performance indicators is noteworthy. The Report had recommended that ASIC develop indicators in addition to existing safety measures, having regard to all of its statutory objectives, including efficiency and business costs. The Report also recommended that any indicators should be reported in the ASIC’s annual report and should be accompanied by guidance in their interpretation, particularly where outcomes may be influenced by factors outside ASIC’s control.

The Treasurer indicated that as an initial priority ASIC should develop indicators for:

- Costs for business of complying with ASIC’s supervisory regimes

- Levels of stakeholder satisfaction with ASIC’s services, and

- Time taken for provision of guidance by ASIC about regulatory obligations in areas where concerns have been raised.

The Treasurer further stated that indicators of the broader economic impact of ASIC’s supervisory conduct should be developed over the longer term.

In its response to the Treasurer’s Statement of Expectations, ASIC acknowledged the need for more comprehensive performance indicators covering all its statutory objectives, including efficiency and business costs. It cautioned that it would take some time to achieve this goal.

6. Performance Measurement

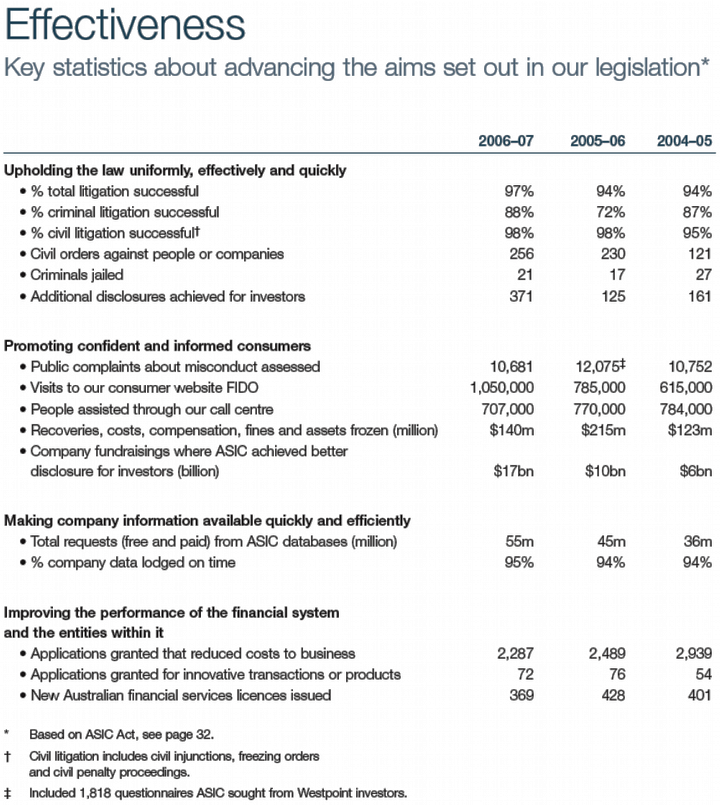

Exhibit 2-2, extracted from the ASIC’s Annual Report, 2006-07, presents the performance indicators that ASIC uses to measure its “effectiveness” in attaining the four statutory objectives.

The information in Exhibit 2-2 makes it clear that the ASIC’s associates “effectiveness” in achieving goals and objectives with its activity levels. Thus, its primary statutory obligation is to improve the performance of the financial system and to reduce business costs. However, ASIC does not attempt to measure the performance of the financial system or the costs of doing business. Instead, it measures the number of applications processed to reduce costs and the number of new financial services firms licensed.

The primary statutory obligation calls attention to improve the financial system in the interests of economic efficiency and development. Thus far, however, ASIC has not provided indicators of the impact of its activities on efficiency and development.

Similarly, the important statutory object of promoting the confident and informed participation of investors and consumers is not the subject of measurement. ASIC reports the number of visits to its website, the number of people it has assisted, etc. These measures are essentially measures of activity and are, at best, indirect indicators of whether investors and consumers are confident and informed.

7. General Observations

It should be noted that ASIC does not regulate the banking sector. This may account for the lack of emphasis on financial system stability.

The Australian experience indicates a degree of tension between the government and the regulatory authority. Whereas the statute clearly assigns economic objectives clear priority over investor protection, it is not entirely clear that the ASIC accepts the hierarchy of objects in the statute.

On its website, ASIC states: “The Australian Securities and Investment Commission Act (2001) requires us to

- Uphold the law uniformly, effectively and quickly

- Promote confident and informed participation by investors and consumers in the financial system

- Make information about companies and other bodies available to the public

- Improve the performance of the financial system and the entities within it.” [8]

This tension between the government’s concern with economic goals and the regulator’s focus on investor protection may be the reason that Australia has not moved more vigorously to establish formal systems of performance measurement.

Exhibit 2-1: Service Charter Measurement

Exhibit 2-2: Key Performance Indicators

Chapter 3

Canada Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions

1. General

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (“OSFI”) was established by Parliament on July 2, 1987 by the OSFI Act. It is an integrated financial regulator, responsible for the regulation and supervision of all federally chartered, licensed or regulated banks, insurance companies, trust and loan companies, cooperative credit associations, fraternal benefit societies and pension plans. The Office of the Chief Actuary conducts actuarial services for the Government of Canada. While OSFI does not regulate securities markets, it has statutory responsibility for the securities business activities conducted iternally by federal financial institutions.

OSFI’s performance standards and measurement approaches are of interest because,

as an industry-funded, integrated financial regulator that operates at arm’s length from the Minister, it bears certain similarities to Canadian securities regulators.

However, as an agency of the federal government, OSFI is subject to reporting requirements of the federal Treasury Board Secretariat. These requirements can be evaluated by the extent to which they focus on measurable outcomes.

2. Statutory Mandate

The OSFI Act creates the Office and establishes its goals and objectives. Section 3 of the Act emphasizes that the goal of the OSFI is public confidence in the financial system:

3.1 The purpose of this Act is to ensure that financial institutions and pension plans are regulated by an office of the Government of Canada so as to contribute to public confidence in the Canadian financial system.

Section 4 of the Act specifies OSFI’s objectives. In regard to financial institutions, s.4(2) emphasizes the objective of safety and soundness:

(2) The objects of the Office, in respect of financial institutions, are

(a) to supervise financial institutions in order to determine whether they are in sound financial condition and are complying with their governing statute law and supervisory requirements under that law;

(b) to promptly advise the management and board of directors of a financial institution in the event the institution is not in sound financial condition or is not complying with its governing statute law or supervisory requirements under that law and, in such a case, to take, or require the management or board to take, the necessary corrective measures or series of measures to deal with the situation in an expeditious manner;

(c) to promote the adoption by management and boards of directors of financial institutions of policies and procedures designed to control and manage risk; and

(d) to monitor and evaluate system-wide or sectoral events or issues that may have a negative impact on the financial condition of financial institutions.

Section 4(3) provides objectives regarding depositors, policyholders and creditors:

(3) In pursuing its objects, the Office shall strive

(a) in respect of financial institutions, to protect the rights and interests of depositors, policyholders and creditors of financial institutions, having due regard to the need to allow financial institutions to compete effectively and take reasonable risks;

It is noteworthy that, unlike the direct objectives given to OSFI for financial institutions, OSFI is here required to “strive” to protect depositors, policyholders and creditors. The consideration of the interests of creditors is also noteworthy, as is the overall objective in depositor protection of requiring consideration of competition and reasonable risk-taking.

It is also noteworthy that section 4(4) of the Act does not assign sole responsibility to OSFI:

(4) Notwithstanding that the regulation and supervision of financial institutions by the Office and the Superintendent can reduce the risk that financial institutions will fail, regulation and supervision must be carried out having regard to the fact that boards of directors are responsible for the management of financial institutions, financial institutions carry on business in a competitive environment that necessitates the management of risk and financial institutions can experience financial difficulties that can lead to their failure.

Thus, the Act recognizes that boards of directors have management responsibilities; that financial institutions operate in a competitive environment; and that failure is always a possibility.

3. Strategic Outcomes

OSFI identifies two strategic outcomes that are primary to its mission and central to its contribution to Canada’s financial system:

-

To regulate and supervise to contribute to public confidence in Canada’s financial system and safeguard from loss. OSFI safeguards depositors, policyholders and private pension plan members by enhancing the safety and soundness of federally regulated financial institutions and private pension plans.

-

To contribute to public confidence in Canada’s public retirement income system. This is achieved through the activities of the Office of the Chief Actuary, which provides accurate, timely advice on the state of various public pension plans and on the financial implications of options being considered by policy makers

4. Performance Reporting

As with federal government departments and agencies generally, OSFI is required to submit a Departmental Performance Report (“DPR”) annually.

As noted therein, OSFI does not measure its performance on the basis of financial-institution closures and pension plan terminations because, as indicated in the OSFI Act, such failures do not necessarily indicate OSFI’s performance. When a failure occurs, OSFI assesses how it performed relative to its early intervention mandate in identifying the situation and intervening appropriately.

In the most recent DPR, OSFI measures its performance according to eight Program Priorities and two Program Support Activities:

Program Priorities

-

(1) Accurate risk assessment of financial institutions and timely, effective intervention and feedback

-

(2) A balanced, relevant regulatory framework of guidance and rules that meets or exceeds international minimums

-

(3) A prudentially effective, balanced and responsive approvals process

-

(4) Accurate risk assessments of pension plans, timely and effective intervention and feedback, a balanced relevant regulatory framework, and a prudentially effective and responsive approvals process

-

(5) Contribute to awareness and improvement of supervisory and regulatory practices for selected foreign regulators through the operations of an International Assistance Program

-

(6) Contribute to financially sound federal government pension and other programs through the provision of expert actuarial valuation and advice

-

(7) Participate in and monitor international work on conceptual changes to accounting standards

-

(8) Ensure that OSFI is in a position to review and approve applications that are submitted for approval under the Basel II capital framework

Program Support Priorities

-

(9) High-quality internal governance and related reporting resources and

-

(10) Resources and infrastructure necessary to support supervisory and regulatory activities

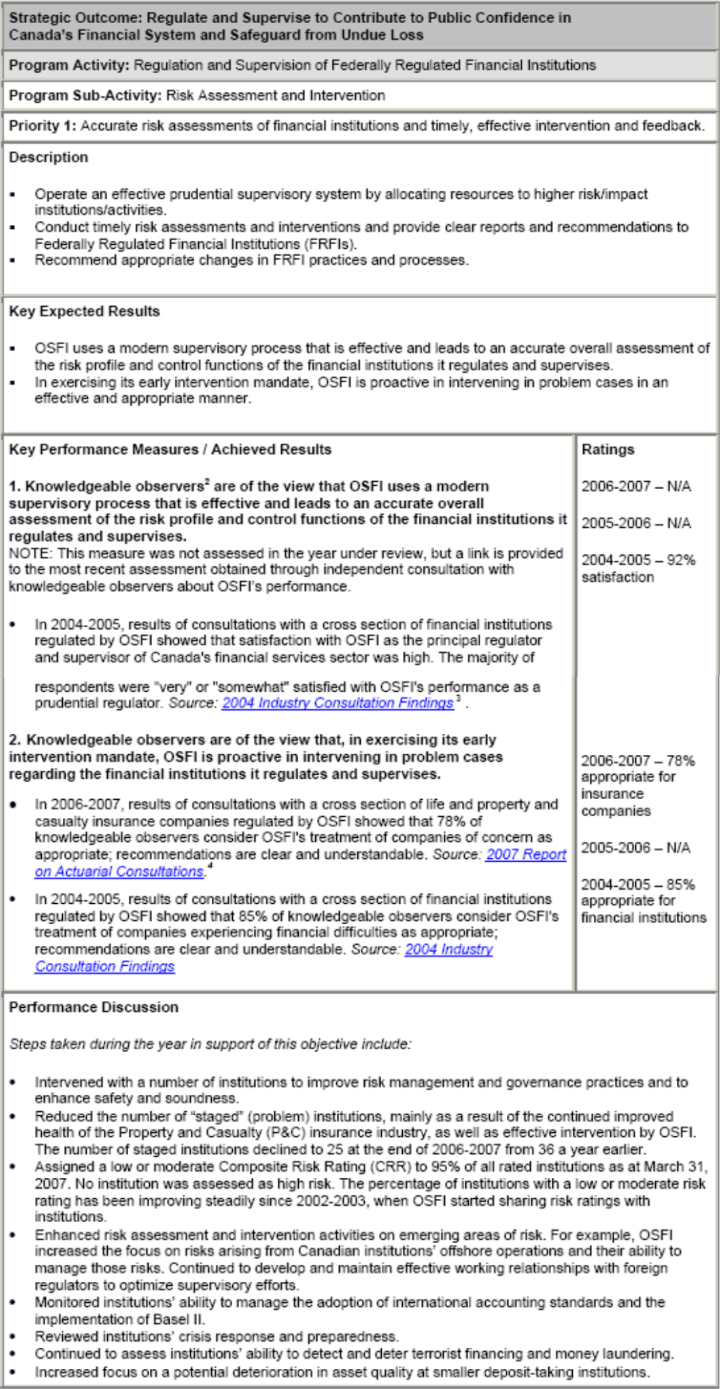

Exhibit 3-1, from the DPR for the period ending March 31, 2007, provides OSFI’s report on its performance against the first priority. Here, OSFI measures its performance by an independent survey of knowledgeable observers, and reports 92% satisfaction with its supervisory process (for the most recent survey in 2005-05) and 78% satisfaction for early intervention for life insurance companies (in 2006-07 survey).

5. Service Standards

In July 2005, OSFI published service standards for those approval-related services to federally regulated financial institutions for which a fee is charged. These service standards comply with the Government’s “Policy on Service Standards for External Fees”. [9] OSFI has developed seven service standards for application to 51 service fees in effect at the time, although it has since stopped charging the full set of fees.

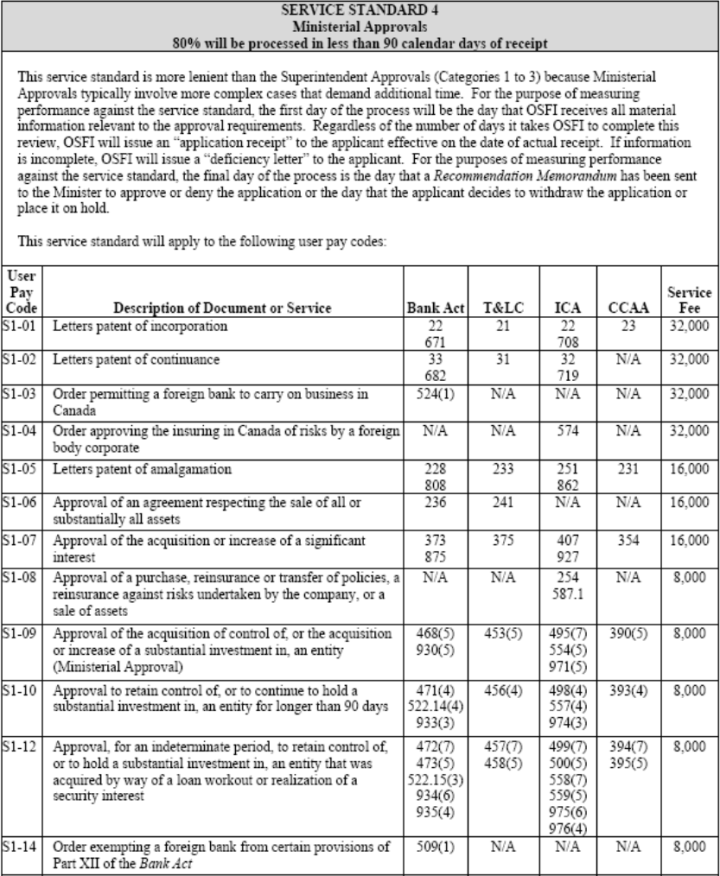

Service Standard 4 covers twenty Ministerial approvals. As shown for twelve thereof in Exhibit 3-2, OSFI’s standard is that 80% of requests will be processed in less than 90 calendar days of receipt.

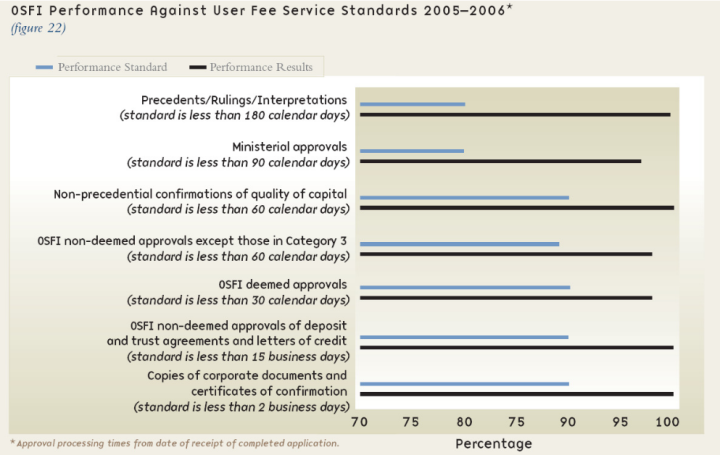

OFSI reported it success in meeting these service standards for the seven categories of services in its 2005-06 annual report. As shown in Exhibit 3-3, the performance standard for Ministerial approvals was 80% of requests handled in 90 days, and OSFI handled over 95% of requests within that period. [10] , [11]

6. General Observations

As a prudential regulator, OSFI is concerned mainly with solvency issues. Its role in regulating market conduct of federal financial institutions is limited, and for this reason, its goals and objectives with respect to investor/consumer protection are limited. In this regard, it does not serve as a model for securities regulation.

However, OSFI is significantly concerned with promoting competition within the financial sector and with the burden of compliance. It is also noteworthy that OSFI applies internationally-developed financial regulations in Canada, most notably the various Basel Accords. It has limited ability to control the significant compliance costs that these regulations impose, as they are held to be justified by the requirements for international financial stability. Thus, OSFI regulates and supervises federal financial institutions with regard to this goal.

In financial regulation, the absence of failures is often taken as the key indicator of soundness and, indeed, of regulatory success. However, OSFI’s mandate does not preclude failures and the occurrence of failure says nothing about OSFI’s performance.

Section 4 of the OSFI Act refers to the need to promote a competitive environment in which financial institutions take risks in the normal course of business; accordingly, OSFI’s mandate does not include such stringent regulation that no failures can occur.

OSFI’s statutory framework is of particular interest for its explicit consideration of competition. A similar view of competition is found, if not always articulated, among provincial securities regulators, who take the view that the regulatory regime is there to protect investors in the event of dealer failure, rather than to ensure that dealers do not fail.

In terms of performance measurement, OFSI seeks to measure outputs where possible. Its use of independent surveys of knowledgeable industry observers to assess its “accurate risk assessment of financial institutions and timely, effective intervention and feedback” provides relevant information on this dimension of its performance.

However, it is clear that when OSFI, in compliance with the requirements set down by Treasury Board, measures its performance against its priorities, its formal performance measurement systems generally measure inputs rather than outputs. Thus, if OSFI makes it a priority to improve its ability to assess risk-taking by banks, then OSFI’s performance report documents the improvements it has put in place to monitor and assess risk.

The Treasury Board performance-reporting requirement emphasizes accountability for expenditures, and like other government departments and agencies, OSFI must prepare detailed accounts of its plans and priorities that require funding. While such accountability is important in itself, it does not identify the appropriate output measure, which for OSFI would be the level of risk in the banking system.

In this regard, OSFI does not publish its risk assessments for individual institutions. While there may be good reason for this, it may be possible to develop aggregate risk measures that would enable it, and the public, to determine whether the financial system is becoming more or less risky over time.

In light of OSFI’s objective relating to competition, entry and exit may be good indicators of success. A regulatory regime in which entry and exit are infrequent may be one in which regulatory barriers to entry are too high, with resulting implications for the efficiency of the sector and the economy as a whole. In addition, OSFI might examine market shares by product line and the extent of changes in rankings of firms by market share as indicators of competition. A sector with a relatively small number of firms might still be highly competitive in this regard.

Exhibit 3–1: Performance Measurement for Risk Assessment

PRIORITY 1

Exhibit 3-2: Service Standards

Exhibit 3-3: Meeting Service Standards

Chapter 4

Ontario Securities Commission

1. General

The Ontario Securities Commission (“OSC”) is the regulatory body responsible for administering and enforcing securities legislation in Ontario. It is an administrative tribunal with quasi-judicial powers.

The Commission’s approach to goals, objectives and performance measurement is of interest for several reasons, including its role as regulator of the largest capital market in the country. Although it has typically viewed regulation through the lens of investor protection, it has increasingly recognized the importance of capital market efficiency and issues relating to the costs of regulation.

2. Statutory Mandate

The Securities Act creates the Commission and instructs the Commission in several parts of the statute. The OSC must interpret its mandate from these various provisions.

-

a. Purpose

Section 1.1 of the Securities Act provides the “purposes” of the Act:

The purposes of this Act are,

(a) to provide protection to investors from unfair, improper or fraudulent practices; and

(b) to foster fair and efficient capital markets and confidence in capital markets. 1994, c. 33, s. 2.

While this purpose clause is not specifically hierarchical, it is noteworthy that the first purpose is investor protection and that market efficiency and confidence are listed second. It might be inferred that the Securities Act accords the former purpose greater importance or significance than the latter.

The reference to fairness in the second principle is oblique. It could be taken to indicate “fair” competition and the acceptability of market outcomes only when they are deemed “fair”. Alternately, it could mean fairness in the sense that all participants face the same rules and that the outcomes of such competition are not the policy concern.

Market efficiency and confidence are clearly economic considerations. The Securities Act is thus concerned with the economic consequences of inefficiency and the lack of confidence on the part of issuers and investors.

-

b. Principles

Section 2.1 of the Act provides “fundamental principles” for the Commission in pursuit of the statutory purposes:

In pursuing the purposes of this Act, the Commission shall have regard to the following fundamental principles:

Balancing the importance to be given to each of the purposes of this Act may be required in specific cases.

The primary means for achieving the purposes of this Act are,

requirements for timely, accurate and efficient disclosure of information,

restrictions on fraudulent and unfair market practices and procedures, and

requirements for the maintenance of high standards of fitness and business conduct to ensure honest and responsible conduct by market participants.

Effective and responsive securities regulation requires timely, open and efficient administration and enforcement of this Act by the Commission.

The Commission should, subject to an appropriate system of supervision, use the enforcement capability and regulatory expertise of recognized self-regulatory organizations.

The integration of capital markets is supported and promoted by the sound and responsible harmonization and co-ordination of securities regulation regimes.

Business and regulatory costs and other restrictions on the business and investment activities of market participants should be proportionate to the significance of the regulatory objectives sought to be realized. 1994, c. 33, s. 2.

The first of these principles to which the Commission is required to have regard is “balance” with respect to the two statutory purposes. This principle seems to suggest that there is, or could be, a conflict between protecting investors and fostering market efficiency and confidence.

The third principle indicates that the Commission should have regard to effective and responsive regulation, achieved by open and efficient administration and enforcement.

The “integration of capital markets” is a fundamental principle for which the Commission is to have regard. This principle suggests that capital markets are more efficient when regulation is coordinated and harmonized. This principle supports the statutory direction to foster fair and efficient markets and market confidence.

The last principle calls attention to “business and regulatory costs”. Thus, the Commission is instructed that such costs should be “proportionate” to the regulatory objectives.

c. Economic efficiency in rule-making authority

Section 143 of the Securities Act gives the Commission the authority to make rules; such rules have the status of regulations. With respect to every rule that the Commission proposes to make under this provision, s.143.2 requires the Commission to publish a notice and s.143.2 (2) requires that the notice contain, among other things,

-

A discussion of all alternatives to the proposed rule that were considered by the Commission and the reasons for not proposing the adoption of the alternatives considered.

-

A reference to any significant unpublished study, report or other written materials on which the Commission relies in proposing the rule.

-

A description of the anticipated costs and benefits of the proposed rule. [12]

The requirement for cost-benefit analysis in rule-making authority emphasizes the goal of economic efficiency, i.e. that proposed rules should be shown to have benefits that exceed the costs they impose. Notably, the Commission is not required to demonstrate this, but it is required to consider the costs and benefits.

3. Performance Measurement

The Commission tracks and reports a variety of statistics, such as the number of registrants, salespeople, hearings, regulated entities’ by-laws reviewed or approved, etc. As discussed above, such statistics are measures of activity; they do not necessarily measure the progress of the agency toward achieving the statutory goals and objectives.

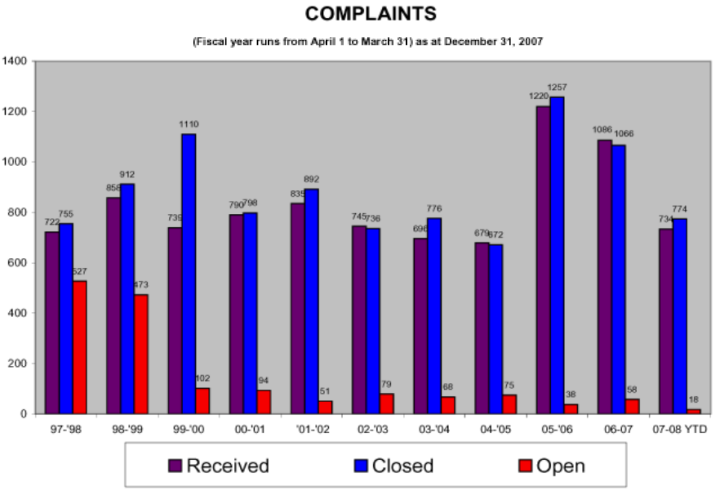

One activity indicator, complaints from the public, does suggest a measure of service that the Commission seeks to attain. Exhibit 5-1 shows how complaints were received and disposed of in the past few years [13] . However, the Commission has not formulated a service standard in this regard, nor has it indicated its success in achieving a prescribed level of response to complaints.

One area where the Commission has established a service standard is with respect to its review of offering documents and applications for exemptive relief. When the OSC is the principal regulator in regard to an issuer of securities, the Commission’s Corporate Finance Branch is charged with reviewing offering documents and applications for exemptive relief from that issuer.

The Corporate Finance Branch has set standards for responding to these filings [14] . For offering documents, it aims to complete the review within 30 working days of receipt. For fiscal 2007, the Branch met this standard 92% of the time, unchanged from the previous year.

For exemptive relief applications, the Branch’s standard is 40 working days. During the 2007 fiscal year, the standard was met for 85% of applications completed, versus 80% in the previous year.

It appears that these two areas are the only ones for which service standards have been established.

4. General Observations

Similarly, the Act gives some precision to the objective of investor protection, i.e. unfair, improper, fraudulent practices. Yet, despite the apparent primacy of investor protection in the Ontario Securities Act, there is no indication of how the OSC views its performance in this area. The available statistics focus on activity levels rather than outputs.

In 2000, the Commission established the Investor Education Fund. This innovative step to promote investor education complements the Commission’s efforts to protect investors through enforcement actions, and indicates that the Commission pursuing the goal of well-informed investors. This initiative is similar to those established in other provinces and is potentially measurable through properly-designed surveys.

In recent years, the Commission has become more focused on competition and efficiency issues with, for example, the elimination of entry barriers through dealer ownership restrictions, the de-mutualization of the Toronto Stock Exchange, and the establishment of a framework for alternative trading systems. The Commission is a leader in the adoption of requirements for cost-benefit analysis in rule-making.

These regulatory innovations evidence a clear and growing concern with capital market efficiency, competition, and the proportionality of costs of regulation. There is, however, no framework in place for the regular assessment of these goals and objectives as yet.

The introduction of service standards in the Corporate Finance Branch is likely to be followed by similar developments in other parts of the Commission. This may lead to further discussion of the goals and objectives of securities regulation in Ontario. Doubtless, the contribution of securities market regulation to financial system stability is a concern of provincial regulators, and concern with this objective will likely increase.

Exhibit 4-1: OSC Complaint Reporting

Chapter 5

Québec Autorité des Marchés Financiers

1. General

The Autorité des marchés financiers (“AMF”) is the body mandated by the government of Québec to regulate the province's financial markets and provide assistance to consumers of financial products and services. [15]

Established under An Act respecting the Autorité des marchés financiers on February 1, 2004, the AMF is unique among Canadian regulatory bodies by virtue of its integrated regulation of the Québec financial sector, notably in the areas of insurance, securities, deposit institutions (other than banks) and the distribution of financial products and services. In addition to the powers and responsibilities conferred on it by its incorporating legislation, the AMF oversees the enforcement of laws in each of the areas it regulates.

2. Statutory Mandate

Securities regulation in Québec is guided by two statutes, the Securities Act and An Act Respecting the Autorité Des Marchés Financiers, R.S.Q., chapter A-33.2.

S.4 of the Autorité’s governing act specifies the Statutory Mission: