Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Creating an Advantage in Global Capital Markets

A Model for Common Enforcement in Canada:

The Canadian Capital Markets Enforcement Agency

and the Canadian Securities Hearing Tribunal

A Research Study Prepared for the

Expert Panel on Securities Regulation

Poonam Puri

A Model for Common Enforcement in Canada:

The Canadian Capital Markets Enforcement Agency

and the Canadian Securities Hearing Tribunal

Biography

Poonam Puri

Poonam Puri is one of Canada’s most respected scholars and commentators on issues of corporate law, securities law, corporate governance, and corporate and white-collar crime. Appointed to York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School in 1997 at the age of 25, and a recipient of its Teaching Excellence Award in 1999, Puri is a prolific scholar who has co-authored/edited three books and written numerous articles and reports. She has an LL.B. from the University of Toronto, where she was the Silver Medalist in her 1995 graduating law class, and she holds an LL.M. from Harvard Law School.

Her work is academically rigorous as well as firmly grounded in the real-time of policy-making. It is for this reason that governments and regulators in Canada and internationally, including Industry Canada, the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC), the Canadian Senate, the Wise Persons Committee on Securities Regulation and the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank, have sought her expertise.

In 2008, she was appointed as one of two research directors of the Canadian Ministry of Finance’s Expert Panel on Securities Regulation, which is seeking input on the best way to develop and implement a model Common Securities Act for Canada. In 2005, she was co-research director of the Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation and also served as a member of the OSC’s Investor Advisory Committee from 2005 to 2007. She was the President of the Canadian Law and Economics Association from 2006 to 2008. She is also currently head of research and policy at the Capital Markets Institute, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto.

A 2005 recipient of Canada’s Top 40 under 40™ award and a 2008 recipient of the Indo-Canada Chamber of Commerce Female Professional of the Year, she was also appointed in 2008 to the board of directors of the Greater Toronto Airports Authority. She is also a member of the board of directors of the Ontario Association of Food Banks, and an inaugural member of the University of Toronto President’s International Advisory Council.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. THE CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND ON ENFORCEMENT

- 3. A MODEL TO IMPROVE ENFORCEMENT IN CANADA

- 4. RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER CRITICAL ISSUES IN SECURITIES REGULATION

- 5. CONCLUSION

Executive Summary

Two of the most intensely discussed topics in Canadian securities regulation today are the need for a common securities regulator and the need to improve enforcement effectiveness in the capital markets. Both of these topics have been debated in government, regulatory, policy and academic circles and have produced significant reports and studies.

Our overall securities regulatory structure in Canada is fragmented, with 13 provincial and territorial securities regulators and several self-regulatory organizations (SROs). Our enforcement system is also fragmented, with the 13 enforcement departments of the commissions, the Integrated Market Enforcement Team (IMET) of the RCMP as well as other police forces, the enforcement departments of the SROs, federal and provincial prosecutors, and judges.

Capital markets are absolutely vital to the strength of the Canadian economy, and effective enforcement of our securities laws plays a large role in maintaining investor confidence. A key criticism of enforcement is the complexity and inefficient allocation of resources that our duplicative and fragmented enforcement system causes. Many resources are spent co-ordinating and cooperating amongst provincial and territorial counterparts, SROs and criminal law authorities. Other criticisms include a lack of enforcement in high profile cases, delays between detection of misconduct and action, and delays in adjudication. There are also concerns about a lack of accountability at each of these enforcement institutions.

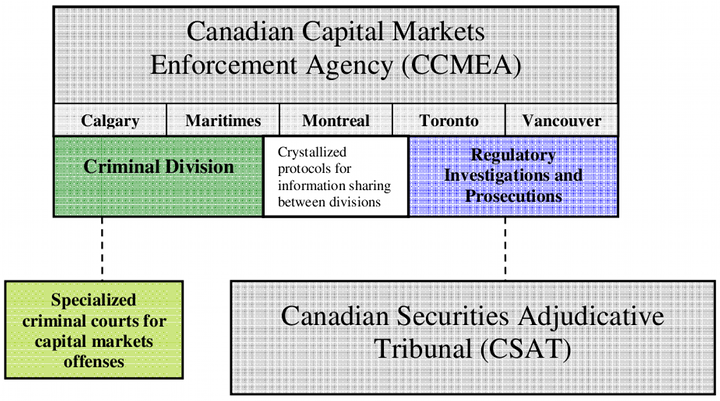

This research study explores and analyzes structural changes that can be made to our enforcement apparatus under the current system of securities regulation with 13 securities regulators and a passport. In an attempt to address some of the major criticisms of enforcement in Canada today, this study proposes and recommends an integrated model for reform to our enforcement structures. This model could be implemented either under the current system or under a common securities regulator. This model would create two new institutions: the Canadian Capital Markets Enforcement Agency (CCMEA), which would be responsible for both criminal and regulatory investigations and prosecutions and the Canadian Securities Adjudicative Tribunal (CSAT), which would hear regulatory matters arising from the CCMEA. The CCMEA’s criminal cases would be heard by specialized criminal courts.

The integrated approach to regulatory reform embodied in the proposed model represents a more efficient and effective use of Canadian enforcement resources than our current system by (i) reducing duplicative and overlapping roles and jurisdictions; (ii) reducing co-ordination costs; (iii) allowing for more consistency in setting enforcement priorities, decision-making, and administering sanctions; (iv) making investor protection more uniform across the country; and (iv) creating one locus of accountability for enforcement activity in Canada.

The model recommended in this paper would:

- remove the IMET from the RCMP and transfer its functions to a division of the CCMEA;

- remove the investigative and prosecutorial functions from the 13 provincial and territorial securities commissions and transfer them to another division of the CCMEA; and

- remove the adjudicative functions from the 13 provincial and territorial commissions and transfer them to an independent CSAT for hearing regulatory matters.

The first part of this model would remove the IMET from the RCMP and create a new, separate police force as a part of the CCMEA. The criminal division of the CCMEA would be responsible for investigating and prosecuting capital markets offences of a criminal nature. The new police force would not be constrained by the history, hierarchy, pay scales, and governance of the RCMP. Under this model, the criminal division of the CCMEA would enforce criminal laws that are contained in a new, separate statute; the offences that currently pertain to the capital markets would be carved out of the Criminal Code and put in a new statute together with any new offences, as Parliament deems necessary. The new statute would also contain additional tools necessary for criminal investigators such as the power to compel testimony from third-party witnesses. The criminal division of the CCMEA would have prosecutors embedded within the organization to allow for greater coordination between investigation and prosecution, greater efficiency and effectiveness in getting cases to trial and a greater likelihood that prosecutorial expertise will develop in this area. Overall, the criminal division of the CCMEA will facilitate more effective and efficient criminal investigations and prosecutions in the capital markets arena.

The next part of this model would merge the investigation and prosecution functions of all the provincial and territorial securities commissions into another division of the CCMEA. This has several advantages over the current system of regulatory enforcement, most predominantly with respect to resources. It would allow for a pooling of regulatory enforcement budgets across the country. It would also reduce or eliminate duplicative functions, such as 13 heads of enforcement, and would significantly reduce co-ordination and cooperation costs for regulators and private participants because there would no longer be 13 separate enforcement departments that have to share information with each other. This change also allows for easier coordination with criminal investigators and prosecutors which would be housed in the other division of the CCMEA. Co-ordination with SROs would also be streamlined and simplified.

Having one agency for both regulatory and criminal investigation and enforcement also allows enforcement priorities to be established at a nationwide level. It will be essential to crystallize the rules on information sharing between regulatory and criminal law investigators so as to ensure compliance with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It is also noteworthy that quasi-criminal offences would no longer exist under this model. Such offences are an unnecessary middle-ground that dilutes both the role and effectiveness of regulatory actions, which are intended to be forward-looking, and criminal actions, which are intended to be reserved for the most egregious cases and have an element of punishment to them.

The CCMEA would have its own funding, governance, accountability and oversight mechanisms. The CCMEA would be created by federal and provincial agreement and would be subject to the oversight of the federal Ministers of Finance, Justice, and Public Works, as well as the provincial and territorial ministers responsible for securities regulation. It would also be required to produce an annual report of its activities that would be made publicly available. Given that actual investigations are best conducted locally, CCMEA would have five offices across the country: Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, Montreal and one in the Maritimes. The head office would be in one of these locales and all of the other offices would report to that office.

In addition to the CCMEA, the model recommended in this paper would also create an independent CSAT by merging the adjudicative/hearing functions of the provincial and territorial regulators into one body. CSAT has several advantages over the current system of regulatory adjudication. First, it would remove the perception of bias created by the fact that the adjudicative function is currently embedded within the organizational structure of almost all of the securities commissions. Second, it would allow for greater consistency in securities regulatory enforcement decisions across the country. It would also allow for more consistent penalties and more uniform investor protection across Canada. Finally, a national independent adjudicative tribunal would allow the tribunal to attract highly qualified adjudicators with the appropriate backgrounds and expertise from across the country. The adjudicative tribunal would have its own funding, governance, accountability and reporting mechanisms, all of which would ensure its effectiveness and independence from the commissions and the CCMEA. CSAT would hear all regulatory matters from the CCMEA, while the CCMEA’s criminal matters would be heard by specialized criminal courts.

The creation of the CCMEA, a national enforcement agency carrying out both criminal and regulatory enforcement, as well as the CSAT, an independent hearing tribunal, is consistent with the general trend that serious misconduct in the capital markets is inter-provincial and increasingly international and therefore needs to be combated with similar structures. Implementation of the model recommended in this paper will lead to a more efficient allocation of resources, less duplication, less overlap, greater consistency and uniformity in the application of our securities laws and better investor protection across the country. Overall, this model will allow us to manage enforcement on a national basis more efficiently and more effectively than the current system.

While this model could be implemented under either the current system with a passport and 13 regulators or a common securities regulator, it would be more effective under a common securities regulator. Under this model, the CCMEA would communicate with the securities regulator(s) in respect of specific files or matters which are under investigation as well as for larger policy issues and priority setting. The CSAT would have no dealings with the securities regulator(s) in respect of specific files (particularly before a case is heard in light of the interest in maintaining independence), but there would be communication on larger policy matters and priorities. The common securities regulator is beneficial for this model because both the CCMEA and the CSAT would be able to deal with a single regulator as opposed to the possibility of 13 regulators in fulfilling their respective mandates.

1. Introduction

The Expert Panel on Securities Regulation was announced by the federal Minister of Finance on February 21, 2008 to provide recommendations on the content, structure, and enforcement of securities regulation in Canada. [1] The Expert Panel’s mandate includes enforcement. The Terms of Reference of the Expert Panel state that it will review and advise on: “How proportionate, more principles-based regulation could facilitate and be reinforced by better, more coordinated enforcement that could include a separate securities tribunal.” [2] The Expert Panel has commissioned this research study to explore and make recommendations on changes that can be made to enforcement structures in Canada under our current system with 13 securities regulators and a passport.

This paper proceeds as follows. Part 2 will briefly set out some context on the enforcement debate by highlighting the importance of the capital markets to the Canadian economy and the importance of effective public enforcement. This part will also briefly summarize the criticisms of enforcement in Canada today. Part 3 will outline the recommended model for a national structure for enforcement in Canada and will discuss the basis upon which this model can improve enforcement effectiveness. It will also discuss the different components of the recommended model and the strengths and weaknesses of each. [3] Part 4 analyzes the relationship between the model recommended in this paper and other critical issues in securities regulation, namely advancing principles-based regulation, advancing proportionate regulation and the larger regulatory structure (passport versus a common securities regulator). Part 5 concludes.

2. The Context and Background on Enforcement

Strong, well-regulated capital markets are essential to the strength of the Canadian economy. Strong capital markets help to maintain the confidence of Canadian and foreign investors in an increasingly global marketplace for capital. Academic studies show that Canada has a higher cost of capital than other countries, after accounting for risk. [4] The Allen Report labelled this the “Canada Discount”, meaning that Canadian companies generally pay more for financing costs for capital than U.S. companies. Part of this discount can reasonably be attributed to our fragmented system of regulation as well as concerns about enforcement effectiveness. The literature shows that strong enforcement of securities laws reduces the cost of capital, and in turn increases liquidity in the capital markets. [5] These studies highlight concerns and inefficiencies with the Canadian enforcement system. One study finds significant insider trading and reporting violations in Canada, based on a review of stock buyback programs and insider trading around material news announcements. [6]

The focus of this paper, as well as most of the recent studies and reports in Canada, is on public enforcement. [7] A key criticism of public enforcement for the purpose of this paper is the complexity and inefficient allocation of resources that our duplicative and fragmented enforcement system causes. Many resources have to be spent on co-ordinating and cooperating amongst provincial and territorial counterparts, SROs and criminal law authorities. Other criticisms include a lack of enforcement in high profile cases, delays between detection of misconduct and action, and delays in adjudication. As well, remedies are only effective on a provincial level and there can be significant variation in the range of sanctions and maximum penalties from province to province. A common perception is that each of the 13 commissions is pursuing its own enforcement agenda with no common setting of priorities. A final concern relates to the lack of accountability of each of these institutions, particularly because there is confusion among stakeholders as to who is responsible for criminal matters versus regulatory matters.

3. A Model to Improve Enforcement in Canada

This part recommends a model to redesign and consolidate Canada’s regulatory enforcement apparatus.

Under this model, two new institutions would be created. The first institution is the Canadian Capital Markets Enforcement Agency (CCMEA), which would be responsible for both regulatory investigations and prosecutions and criminal investigations and prosecutions. This model would separate IMET from the RCMP and create a new, separate division within the CCMEA to investigate capital markets offences of a criminal nature. Similarly, this model would carve-out the investigation and prosecution functions from the provincial/territorial securities commissions and combine them into another division of the CCMEA that would be responsible for investigating and prosecuting regulatory offences.

The second institution that would be created is the Canadian Securities Adjudicative Tribunal (CSAT), which would remove the adjudicative function from each of the 13 provincial and territorial securities commissions and combine them into one national hearing tribunal.

The key criteria in evaluating the recommended model include:

- Ability to deal with key criticisms of enforcement;

- Constitutionality validity;

- Stability of structure;

- Cost and cost effectiveness; and

- Transition path and costs.

The model recommended in this paper presents significant benefits for enforcement effectiveness in Canada, particularly by facilitating the efficient allocation of enforcement resources, greater consistency in the application and enforcement of our securities laws, more uniform investor protection across the country and greater accountability of the institutions that enforce our securities and criminal laws in the context of the Canadian capital markets. The CCMEA and its divisions as well as CSAT are discussed in more detail below.

(i) The Canadian Capital Markets Enforcement Agency (CCMEA)

(a) A Criminal Division within the CCMEA

This part would s eparate the IMET from the RCMP and create a new, separate division within the CCMEA to investigate and prosecute capital markets offences of a criminal nature. This division would house specialized investigators as well as a cadre of specialized prosecutors who work closely with investigators to achieve efficient, timely and fair criminal investigations and prosecutions.

i. Concerns with Criminal Enforcement and IMET

The RCMP and the IMET have been subject to considerable criticism and study. Justice Peter Cory and Professor Marilyn Pilkington’s report for the Allen Committee noted several concerns about IMET, including human resource issues, information sharing concerns and accountability and management issues [8] . Nick Le Pan’s report on the IMET also raised similar concerns. [9] Le Pan’s recommendations included enhanced leadership for the IMET and clarifying accountability within the RCMP. He also suggested more discipline and results-oriented management. Le Pan also highlighted specific human resources measures to address pay scales, high vacancy rates, staff turn-over, promotions and opportunities. Many of Le Pan’s recommendations are specific to the current structure of the IMET within the RCMP.

Figure 1: The Recommended Model – The Canadian Capital Markets Enforcement Agency (CCMEA) and the Canadian Securities Administrative Tribunal (CSAT)

While Le Pan’s recommendations reflect reform at the margins and within the existing institutions, it is important to note that separating the IMET from the RCMP – a much larger reform proposal – is being actively considered by stakeholders. At a 2007 hearing of the Standing Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce, RCMP Deputy Commissioner Pierre-Yves Bourduas, indicated that there had been “much discussion” about whether the IMET should retain their connection to the RCMP or whether a separate agency should be created. [10]

ii. Opportunities

Separating the IMET from the RCMP and creating a criminal division within the CCMEA would give the IMET a better chance of thriving, rather than attempting to re-invent itself within the confines of the RCMP structure and hierarchy. The reality is that the IMET is comprised of about 150 people in a RCMP force of over 26,000 strong. This is less than one per cent of the total staff of the RCMP. Given these numbers, as well as other constraining factors, the IMET cannot realistically change much within the constraints of the RCMP structure.

The new criminal division of the CCMEA could structure its own pay and promotion scale without regard to the RCMP’s rigid structures. During the course of a lengthy investigation, an officer could carry on his or her position within a separate police agency and would not be diverted to perform other duties within the RCMP, which the existing structure permits and encourages. To this end, the new agency would afford officers/investigators a greater likelihood of building their careers and earning promotions without having to move out of this specialized agency.

The new criminal division of the CCMEA could enforce existing Criminal Code offences that relate to the capital markets. However, this would be a good opportunity to create a new piece of federal legislation that focuses exclusively on capital market offences, as we have done in the past for narcotics control and terrorism. This new statute would carve out the existing capital markets offences from the Criminal Code and create new offences as required. The new legislation should also contain much-needed tools for criminal investigators and prosecutors, such as the power to compel testimony from third-party witnesses. Currently, the power to subpoena testimony from third-party witnesses is available to securities regulators, but not the police, which is a serious constraint in addressing capital markets misconduct. [11] Indeed, allowing prosecutors to be an integrated part of the CCMEA will help address the current criticism that prosecutors do not have the resources, interest or expertise to handle capital markets offences of a criminal nature.

A key criticism of this approach is that a separate police force for capital markets offences will be very costly, given that it will have to establish its own infrastructure for human resources, information technology, and related police services. Funding for the CCMEA and its division is discussed below, but this concern may be addressed, in part, by devising a structure which would allow the new agency to piggyback off certain types of existing infrastructure of the RCMP or another entity. For example, Canadian Police College and the Criminal Intelligence Service of Canada are two institutions that are separate from the RCMP, but draw on its strengths and infrastructure as needed.

(b) A Regulatory Enforcement Division within the CCMEA

The part of the model would combine the investigation and prosecution functions of the provincial securities commissions into another division of the CCMEA that would be responsible for securities regulatory investigations and prosecutions.

This part would carve out the investigation and prosecution functions from the provincial securities commissions and combine them into another division of the CCMEA. This division would investigate and prosecute regulatory offences. Quasi-criminal offences would no longer be an option available to regulators. Rather, there would be clear demarcation between regulatory offences, which are intended to correct the market going forward and criminal offences, which will be reserved for the most egregious cases of misconduct and wrongdoing. Using this approach, the provincial/territorial securities commissions would retain control over other substantive areas including policy-making, corporate finance, and mergers and acquisitions.

Having a single body responsible for regulatory investigations and prosecutions presents several advantages over the current system of enforcement.

First, this model will allow for significant cost savings and efficiencies. The budgets of the 13 enforcement departments could be pooled and used collectively in a single agency and duplicative roles and duties, such as 13 heads of enforcement, can be reduced thereby freeing up a greater portion of the budget for actual cases. As well, some fraction of the existing budgets currently used to co-ordinate, co-operate and harmonize operations amongst the 13 enforcement departments could be applied to more substantive matters. The CCMEA would only have five regional offices in total, thereby reducing the overall costs associated with co-ordination and co-operation between offices.

Second, this model will allow enforcement priorities to be established at a single, common, national level. This will be a tremendous benefit but it should be underscored that actual investigations and prosecutions would continue to take place through several local offices, which is one of the strengths of our current system. This model would allow for a uniform level of investor protection across the country.

Finally, this model will allow for more effective and efficient co-ordination between the criminal and regulatory divisions of the CCMEA. There will be better co-ordination with the SROs (which are national) and international enforcement bodies than our current system. This model will also allow for more credible enforcement co-ordination with international counterparts. This is important in light of the fact that enforcement is more and more frequently national, if not international, in scope.

(c) Creation and Constitutionality of the CCMEA

The CCMEA would be created through federal and provincial government agreement. The federal government’s involvement is necessary because of the CCMEA’s criminal division. In respect of the regulatory division of the CCMEA, the provinces could cede their authority over investigation and prosecution of securities regulatory matters and the federal government could pass a statute creating the agency and setting out the framework within which it operates. Alternatively, a private sector body, such as the model used for the Canadian Public Accountability Board (CPAB) could be considered.

In considering the possibility of a common enforcement agency without a common securities regulator, it will become necessary to have a common set of offences. Without a common understanding of regulatory offences across the country it will not be clear which province or territory’s securities act should apply, particularly when dealing with misconduct that is often inter-provincial and international. It is essential that the provinces and territories agree on a common set of securities regulatory violations that can be housed in one piece of legislation.

(d) Governance of the CCMEA

The CCMEA would have five offices: one in each of Calgary, the Maritimes, Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. One of these offices would constitute the head office and all other offices would report to the chief of the agency. The local offices should be powerful, meaningful and robust. They should be staffed locally, and, to the extent feasible, they should investigate and prosecute locally. There is a significant value to investigations being done on the ground. It is also important to have prosecutions and hearings take place in the region in which the misconduct took place and/or where investors were harmed. The staff of the agency and each office should be drawn from existing staff at the commissions, thereby drawing on the strength and expertise of those individuals.

The CCMEA would be accountable to the federal ministers of finance, justice and public works, as well as the provincial/territorial ministers responsible for securities regulation. The agency would be required to produce an annual report that would be made publicly available.

Clear, consistent, bright-line rules would need to be crystallized to ensure that any information shared between the criminal and regulatory divisions of the CCMEA in the context of investigations is fair, reasonable, necessary and in compliance with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. [12]

(e) Funding of the CCMEA

The CCMEA’s funds would come from two sources. The funds that are currently used for enforcement by the provincial securities commissions should be re-allocated by the provinces/territories to the regulatory division of the new CCMEA under this model. The Charles River and Associates Study conducted for the Wise Persons Committee suggests that the provinces have a collective annual enforcement budget of $21 million. [13] Howell Jackson’s more recent study for the Allen Committee indicates that the provinces’ collective overall regulatory budgets were $143 million; if approximately 20% is used for enforcement, then there is an annual sum of approximately $28 million available for the regulatory enforcement division of a new national agency. [14]

With respect to the budget for the criminal division of the CCMEA, the starting point should be the funds that are currently allotted to the IMET under the RCMP. These funds should be transferred to the new entity. The federal government allocated $30 million per year to the IMET when they were created in 2003, and a further $10 million a year was allocated to the IMET starting April 2008. [15] While there will be some significant one-time start-up costs, the $40 million allotment from the federal government should continue to fund annual operations.

(ii) An Independent Canadian Securities Adjudicative Tribunal (CSAT)

The recommended model would carve out the adjudicative function from the 13 provincial and territorial securities commissions and combine them into a national independent securities adjudicative tribunal.

(a) Concerns with the Current System

A key concern with the current system is that the adjudicative function is embedded within the organizational structure of many of the securities commissions, creating a reasonable perception of bias. One exception is Quebec, where there is a separate provincial securities adjudicative tribunal, and the experience appears to be quite favourable. [16]

There have been many calls in the last several years for adjudication to be independent of the securities commissions in Canada. [17] It is also significant to note that leading capital markets jurisdictions such as the U.S. and the U.K. have independent hearing tribunals for securities matters. In the U.S., admin istrative law judges hear Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) administrative proceedings. In the U.K, the Financial Services and Markets Tribunal is wholly independent of the Financial Services Authority (FSA) with separate funding, staff and operations.

Outside of securities regulation, a successful example of adjudication separate from the administration and enforcement in Canada would be the Competition Tribunal, which is separate from and independent of the Competition Bureau.

(b) Opportunities under the CSAT

There are three key advantages of CSAT as compared to the current system.

The first advantage is that an independent tribunal would address the perception of bias issue head-on. Adjudication should be separated from the rest of the commissions not because it is legally required, but rather as a matter of good governance. In the absence of formal separation of adjudication from enforcement, the commissions try to address the situation by creating internal partitions between enforcement and the commissioners to ensure that the commissions are free of bias when hearing cases. This, however, has deleterious effects. As the Osborne committee noted, the result is that enforcement becomes a “black hole within the Commission,” operating on its own without its priorities, policies or practices being subjected to the commissioners’ advice and oversight, even though it is one of the most important departments in the organization. [18] If the adjudication function is removed from the commissions, this internal separation between enforcement and all else is not necessary and the commissioners can take a more hands-on approach to establishing priorities and practices of enforcement. [19]

It should be noted that some have argued that separation of adjudication from the rest of the commissions would make it much harder for the commissions to fulfill their mandate. For example, Anisman believes there is a strong inter-relationship between the adjudicative and policymaking functions and separating them would therefore make it difficult to carry out either function. [20] Others have argued that a separate tribunal will result in over-proceduralization and that there will be too many appeals from tribunal decisions to the courts. However, the experience of the Quebec tribunal, as well as other independent hearing bodies is instructive – these concerns have not surfaced in practice and the tribunals appear to be operating fairly, effectively and efficiently.

The second advantage of a national tribunal is that it would allow us to find the best qualified candidates from across the country to adjudicate on securities law matters. Under this model, a roster of expert adjudicators would be created, drawing on retired judges, industry participants, lawyers, and other professionals, who would be available to hear cases across the country. These individuals would not be involved in the provincial securities commissions in any way. While some current vice-chairs and commissioners would not be interested in being adjudicators on this tribunal because they also enjoy the policy work at the commissions, I am confident that there will be a strong pool of well-qualified candidates who are interested only in adjudicating.

The third advantage of a national tribunal is that it would allow for greater consistency in the interpretation of our substantive laws and sanctioning principles as well as actual sanctions, as compared to our current system with 13 separate hearing functions at the commissions. Greater consistency in the application of the law is particularly important, in light of the federal government’s interest in advancing principles-based regulation. As a general matter, under principles-based regulation, the regulator provides very high-level guidance and relies much more heavily on industry participants, as well as those who hear cases, to interpret those provisions. This issue is discussed in more detail below.

As a related matter, another benefit of a national tribunal is that it may be possible to include a mechanism that would make sanctions apply across the country, again addressing another challenge with the current fragmented system of enforcement.

(c) Constitutionality and Creation of the CSAT

There appears to be some political will for CSAT. The Council of Ministers responsible for Securities Regulation noted in its 2007 Progress Report that it is examining the potential benefits of establishing an independent securities tribunal. [21]

The provinces and territories would need to decide how to create the tribunal. They could create it on their own by provincial agreement using a memorandum of understanding and delegation or a statute with delegation of powers to the tribunal. From a constitutional perspective, one would need to ensure that the provinces are delegating only those powers to the tribunal which they themselves have jurisdiction over. Alternatively, the tribunal could be created by agreement between the provinces and the federal government, where the provinces voluntarily cede their adjudicative powers over securities matters to the federal government. The federal government would then pass a statute creating the tribunal.

(d) Governance of the CSAT

The tribunal proposed under this model would have a maximum of 4-7 chairpersons and a maximum of 13-17 lay members who would be available to hear cases across the country. The chairpersons and lay members could be nominated (or appointed) by each of the provinces or territories to ensure local and regional diversity. By point of reference, the Competition Tribunal in Canada has a maximum of six judicial members and a maximum of eight lay members, appointed by the Governor-in-Council. The Financial Services and Market Tribunal in the U.K. has eight legally qualified chairmen and seventeen lay members. [22]

Each case should be heard by one chair and two lay members, and, ideally, should be heard in the province/territory in which the misconduct took place.

The executive chair of the tribunal (to be selected from the 4-7 chairs) would be responsible for reporting to the federal Minister of Finance and the provincial/territorial ministers responsible for securities regulation. The tribunal would also produce an annual report that would be publicly available. All hearings should be public unless there is a compelling reason to have an in-camera hearing.

(e) Funding of the CSAT

The tribunal should ideally be funded by market participants and investors who benefit from its existence and effective operation. However, market participants should not be funding the tribunal directly, nor should the funds be coming directly from the securities commissions. Rather, the participating provinces and federal government should directly fund the tribunal.

4. RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER CRITICAL ISSUES IN SECURITIES REGULATION

The Expert Panel has a mandate to explore ways in which principles-based regulation and proportionate regulation could be advanced in Canada. It is also charged with comparing the current system of securities regulation with 13 regulators and a passport with the possibility of a common securities regulator. Therefore, it would be useful at this stage to explore t he model recommended in Part 3 above and its relationship to principles-based regulation, proportionate regulation and the larger securities regulatory structure (a passport versus a common securities regulator).

(i) Advancing Principles-Based Regulation

Principles-based regulation is a regulatory philosophy whereby the regulator provides high-level guidance to market participants, instead of detailed, specific rules. [23] Many reports and studies at the domestic and international levels have endorsed principles-based regulation. The FSA, a strong advocate of this philosophy, argues that its approach results in effective, outcomes-based regulation, and not simply outsourcing, deregulation or reduced regulation. Below, I highlight a number of challenges and issues that need to be considered when discussing the interplay between principles-based regulation and enforcement.

The first challenge is that principles-based regulation is usually coupled with low levels of formal enforcement actions. The regulator prefers to tailor the regulatory response to specific situations in order to encourage better outcomes, instead of following a prescribed process for every enforcement scenario that will lead to a hearing and sanction. The focus is much more on compliance, cooperation and inducing law-abiding behavior. As a result of this philosophy, the FSA, for example, does not take as many formal enforcement actions as the SEC. This poses a challenge for Canadian securities regulators who are often criticized for not doing as much as the U.S. in their enforcement actions. [24] If Canada is moving towards a regulation philosophy that is more principles-based, then we will have to accept that our enforcement strategy may also shift. The result may be less of a focus on back-ended, high-volume and high-penalty enforcement actions.

A second concern is that the use of general principles to trigger enforcement actions and sanction behavior may be unfair in certain circumstances. The FSA has stated that it will pursue enforcement actions based on a breach of a principle, even if a specific rule has not been violated. This approach raises a concern about fairness for respondents in enforcement actions. As highlighted by the Allen Report, there has been a lot of criticism in Canada of regulatory use of the “public interest power” and the perception that it is viewed as an after-the-fact “gotcha” mechanism. If we are going to legitimately advance principles-based regulation, then we need to provide market participants with reasonable notice and fair guidance about what constitutes acceptable behavior and what does not.

Overall, there appears to be synergies between the recommended model and principles-based regulation. The recommended model will allow for greater consistency and uniformity in the application and interpretation of our securities laws by investigators and prosecutors within the CCMEA and adjudicators at the CSAT.

Having said that, moving IMET out of the RCMP and into a division of the CCMEA should have minimal impact on the implementation of principles-based regulation at the regulatory level. The interest in principles-based regulation in Canada appears to be at the level of securities regulation and regulatory bodies, and does not appear to be at the criminal law level. Criminal law offences have traditionally required a greater degree of specificity because it is thought that if an individual is to be exposed to the potentially severe repercussions under the Criminal Code, then the individual should be entitled to know what exactly the prohibited behavior is. This would suggest that criminal sanctions require very clearly defined rules, as opposed to principles. On the other hand, administrative sanctions are not seen to carry as severe repercussions (although one can question this) and, as a result, a greater deal of ambiguity is tolerable under these circumstances.

The application and interpretation of securities law principles should become more consistent when considering the CCMEA’s regulatory enforcement division since there would only be one investigative and adjudicative body interpreting the principles as opposed to 13 separate enforcement departments. As a practical matter, the investigation and prosecution staff at this agency would have significant discretion in interpreting the principles that have been produced by the securities commissions. As a result, agency staff should have expertise and be very well qualified so that they can interpret the principles in a way that best serves the public interest. Also, there should be some reasonable level of communication and dialogue between the agency and the securities commissions about commission policy initiatives for the benefit of enforcement agency staff.

Similarly, the case for the CSAT becomes stronger when considered in light of the interest in advancing principles-based regulation. One national panel, rather than 13 separate hearing panels, would allow for greater consistency in the application of principles, since the same group of individuals would be hearing cases throughout the country. However, some would argue that a principles-based system provides too much discretion and power to tribunal members to decide upon the fate of those before them. This issue is best addressed by ensuring a fair and transparent appointments process that includes a mechanism for nominations from relevant stakeholder groups. There is little room for criticism if the quality of the appointments is impeccable. As well, it simply has to be acknowledged that principles-based regulation requires a high degree of faith in both market participants and adjudicators to interpret principles appropriately.

(ii) Advancing Proportionate Regulation

Proportionate regulation refers to securities regulation that is based on the size of the issuer, as well as its market experience and resource capacities. [25] Also known as “scaled” or “risk-based regulation,” it operates on the rationale that smaller issuers pose less risk to the market (although this is debatable) and that they may lack the staff and resources necessary to comply with onerous regulatory requirements. There is also a view that larger issuers can justifiably be subject to less regulation on the basis that there is more market oversight of their activities. Given that the Canadian capital market has clusters of different types of issuers across the country, proportionate regulation can also have local and regional impacts.

Overall, effective implementation of proportionate regulation will require that staff at the regulatory division of the CCMEA and the members of the CSAT are well-qualified with significant expertise and have the ability to exercise good judgment about when to treat respondents differently.

To properly effect proportionate regulation, investigators and prosecutors at the regulatory division of the CCMEA need to be extremely skilled. The staff of the agency will have to exercise good judgment in deciding whether to pursue a matter against a particular firm and which sanctions to apply. While staff will want to recognize legitimate differences under proportionate regulation, the challenge will be to balance this goal with the goal of consistency and uniformity in the application of securities laws.

This paper does not focus onthe relationship between the criminal division of the CCMEA and proportionate regulation, since the interest in proportionate regulation is at the regulatory level. This is not to suggest that proportionality is not a concern in criminal law when it comes to handing down sanctions. The Criminal Code explicitly states that a given sentence “must be proportionate to the gravity of the offence and the degree of responsibility of the offender.” [26] However, an in-depth analysis of this relationship is beyond the scope of this paper.

To give effect to proportionate regulation in the context of the hearing tribunal, the members of the CSAT would need to have significant expertise so that they can effectively apply principles of proportionality in their decision-making. Tribunal members will have to have a nuanced approach to imposing sanctions. Sanctions may reasonably differ for the same offence carried out by firms of varying sizes and risk profiles. It will be challenging for tribunal members to find a balance between advancing proportionate regulation which requires recognition of legitimate differences leading to different outcomes and the interest in ensuring consistency and uniform investor protection.

(iii) Passport Versus Common Securities Regulator

The recommended model could be implemented under the current system with 13 regulators and a passport system. The model is also compatible with a common securities regulator. Successful implementation of the model will require federal and provincial co-operation and agreement on many fronts. It will also require the provinces to give up control over several aspects of enforcement activities. However, the recommended model is the most comprehensive structural solution to some of the most critical enforcement issues we face in Canada.

There seems to be some political will for the CSAT and the experience of the Quebec tribunal is favourable in this regard. There would have to be some negotiation in regard to how it would be created and its governance, accountability, and transparency structure, but it appears feasible.

The CCMEA would be more difficult to achieve. Separating the IMET from the RCMP and placing it within a division of CCMEA is not what makes this model challenging since the criminal law is squarely within federal jurisdiction. The challenge will be in getting agreement amongst the provinces in transferring the 13 enforcement departments over to the other division of the CCMEA. This will require agreement on a large number of issues and also require the commissions to give up a significant amount of control over an important area. In some sense, this aspect of the recommended model could be just as difficult to negotiate and achieve as a common securities regulator.

While this model could be implemented under either the current system with a passport and 13 regulators or a common securities regulator, it would be more effective under a common securities regulator. Under this model, the CCMEA would communicate with the securities regulator(s) in respect of specific files or matters which are under investigation as well as for larger policy issues and priority setting. The CSAT would have no dealings with the securities regulator(s) in respect of specific files (particularly before a case is heard in light of the interest in maintaining independence), but there would be communication on larger policy matters and priorities. The common securities regulator is beneficial to this model because both the CCMEA and the CSAT would be able to deal with a single regulator as opposed to the possibility of 13 regulators in fulfilling their respective mandates.

5. CONCLUSION

This research study explored and analyzed structural changes that can be made to our enforcement apparatus under the current system of securities regulation with 13 securities regulators and a passport. The paper recommended a model that represents a comprehensive solution to address some of the major criticisms of enforcement in Canada today. This model can be implemented under the current system with 13 regulators and a passport or under a common securities regulator.

This model would create two new institutions. It would create a Canadian Capital Markets Enforcement Agency (CCMEA), which would be responsible for both criminal and regulatory investigations and prosecutions. This model would also see the creation of an independent Canadian Securities Adjudicative Tribunal (CSAT), which would hear regulatory matters from the CCMEA. CCMEA’s criminal cases would be heard by specialized criminal courts.

The recommended model’s integrated approach to reform would allow us to more efficiently and effectively use our enforcement resources in Canada. Successful implementation of this model will allow us to (i) reduce duplicative and overlapping roles and jurisdictions; (ii) reduce co-ordination costs; (iii) have more consistency in the setting of enforcement priorities, decision-making, and laying of sanctions; (iv) make investor protection more uniform across the country; and (iv) create one locus of accountability for enforcement activity in Canada.

This model would remove the IMET from the RCMP and create a new police force as a division of the CCMEA. The criminal division of the CCMEA would be responsible for investigating and prosecuting capital markets offences of a criminal nature. This new police force would not be constrained by the history, hierarchy, pay scales, and governance of the RCMP. Under this model, the criminal division of the CCMEA would enforce criminal laws that are contained in a new, separate statute; the offences that currently pertain to the capital markets would be carved out of the Criminal Code and put in a new statute together with any new offences, as Parliament deems necessary. The new statute would also contain additional tools necessary for criminal investigators such as the power to compel testimony from third party witnesses. The criminal division of the CCMEA would have prosecutors embedded within the organization so that there is greater coordination between investigation and prosecution, greater efficiency and effectiveness in getting cases to trial and a greater likelihood that prosecutorial expertise will develop in this area. Overall, the criminal division of the CCMEA will allow for more effective and efficient criminal investigations and prosecutions in the capital markets arena.

The second aspect of this model would see the investigation and prosecution functions of all the provincial and territorial securities commissions merged into another division of the CCMEA. This would result in several advantages over the current system of regulatory enforcement, most predominantly with respect to resources. It would allow for a pooling of regulatory enforcement budgets across the country. It would also reduce or eliminate duplicative functions, such as 13 heads of enforcement, and will significantly reduce co-ordination and cooperation costs for regulators and private participants because there would no longer be 13 separate enforcement departments that have to share information with each other. This change would also allow for easier coordination with criminal investigators and prosecutors which would be housed in the other division of the CCMEA. Co-ordination with SROs would also be streamlined and simplified.

Having only one agency for both regulatory and criminal investigation and enforcement will also allow for enforcement priorities to be established at a nationwide level. It is noteworthy that quasi-criminal offences would no longer exist under this model, as they are an unnecessary middle-ground that dilute both the role and effectiveness of regulatory actions, which are intended to be forward-looking, and criminal actions, which are intended to be reserved for the most egregious cases and have an element of punishment to them.

Clear, consistent, bright-line rules would need to be crystallized to ensure that any information shared between the criminal and regulatory divisions of the CCMEA in the context of investigations is fair, reasonable, necessary and in compliance with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In addition to the CCMEA, the recommended model would also create an independent CSAT by merging the adjudicative/hearing functions of the provincial and territorial regulators into one body. The CSAT has several advantages over the current system of regulatory adjudication. First, it would remove the perception of bias that is created by the fact that the adjudicative function is currently embedded within the organizational structure of almost all of the securities commissions. Second, it would allow for greater consistency in securities regulatory enforcement decisions across the country. It would also allow for more consistent penalties and more uniform investor protection across the country. Finally, a national independent adjudicative tribunal would allow the tribunal to attract highly qualified adjudicators with the appropriate backgrounds and expertise from across the country. The adjudicative tribunal would have its own funding, governance, accountability and reporting mechanisms, all of which would ensure its effectiveness and independence from the commissions. The CSAT would hear all regulatory matters from the CCMEA.

The creation of the CCMEA, a national enforcement agency carrying out both criminal and regulatory enforcement, as well as the CSAT, an independent hearing tribunal is consistent with the general trend that serious misconduct in the capital markets is inter-provincial and increasingly international and therefore needs to be combated with similar structures. Implementation of the model recommended in this paper will lead to a more efficient allocation of resources, less duplication, less overlap, greater consistency and uniformity in the application of our securities laws across the country, and better investor protection. Overall, the model recommended in this paper would allow us to manage enforcement on a national basis more efficiently and more effectively. It is best pursed in conjunction with a common securities regulator.

[1] Expert Panel on Securities Regulation (2008) online: www.expertpanel.ca .

[2] See paragraph 3 of the Expert Panel’s Terms of Reference, online: Expert Panel on Securities Regulation http://www.expertpanel.ca/eng/about-us/terms-of-reference/index.php .

[3] See also, Poonam Puri, “Of Regulatory Reform and Enforcement Effectiveness: Models for a Common Enforcement Agency for Canada” (Toronto: Capital Markets Institute, 2008).

[4] See Luzi Hail and Christian Leuz, “International Differences in the Cost of Equity Capital: Do Legal Institutions and Securities Regulation matter?”, (2006) Journal of Accounting Research, 44:3 485, where the authors observed that the cost of equity capital is 25 basis points higher in Canada than in the United States; also see Michael R. King and Dan Segal, “Valuation of Canadian vs. U.S. Listed Equity: Is there a Discount?” (2003) Bank of Canada Working Paper 2003-6 (March 2003) which came to the conclusion that Canadian public companies are valued significantly lower than those in the United States while attempting to control for a number of variables; See also Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation in Canada, Canada Steps Up Final Report (2006) (Toronto: Task Force) online: <www.tfmsl.ca> at 24. (“Allen Report”).

[5] See, for example, U. Bhattacharya, “Enforcement and its Impact on Cost of Equity and liquidity of the Market” in Volume VI of the Allen Report, supra note 4.

[6] William McNally and Brian Smith, “Do Insiders Play by the Rules?” Canadian Public Policy (2003).

[7] For example, the Allen Report, supra note 4, did not focus on private enforcement in their report or recommendations. However, some of the underlying research commissioned by that Task Force did analyse these issues: See The Hon. Peter de C. Cory, C.C. & Professor Marilyn L. Pilkington, “Critical Issues in Enforcement” in Canada Steps Up, Report of the Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation in Canada,Volume 6, 2006, available at http://www.tfmsl.ca ; See also, Mary Condon and Poonam Puri, “The Role of Compliance in Securities Regulatory Enforcement” in Canada Steps Up, Report of the Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation in Canada, Volume 6, 2006, available at http://www.tfmsl.ca .

[8] Cory and Pilkington, Ibid .

[9] Available online at: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/imets/report_le pan2007_e.pdf .

[10] “Proceedings of the Standing Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce,” Issue 25 – Meeting of June 13, 2007, at 17, online: <http://www.parl.gc.ca/39/1/parlbus/commbus/senate/Com-e/bank-e/pdf/25issue.pdf>.

[11] This is a contentious issue because of concerns surrounding the rights and protections offered to individuals (both individuals who are under investigation as well as third parties not under investigation) under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

[12] See R. v. Jarvis , [2002] 3 S.C.R. 757 ; See also, Lisa Austin. Information Sharing and the 'Reasonable' Ambiguities of Section 8 of the Charter , 57:2 (2007) University of Toronto Law Journal at 499.

[13] Charles River and Associates, “Securities Enforcement in Canada: The Effect of Multiple Regulators” (Wise Persons Committee Research Study, 2003) Table 3 at 469; available online at http://www.wise-averties.ca/reports/WPC_10.pdf .

[14] See H. Jackson, “Regulatory Intensity in the Regulation of Capital Markets: A Preliminary Comparison of Canadian and U.S. Approaches” at 469 in Allen Report and Research Studies, supra note 4. See also, P. Puri, “Enforcement Effectiveness in the Canadian Capital Markets”, (Toronto: Capital Markets Institute,

2005) at 23.

[15] See “Integrated Market Enforcement Teams Helping Protect Canada’s Capital Markets” (2007) online: RCMP Integrated Market Enforcement Teams <http://www.grc.gc.ca/imets/report_2007_e.htm>

[16] See Stephane Rousseau, The Québec Experience with an Independent Administrative Tribunal Specialized in Securities, Research Study Prepared for the Expert Panel on Securities Regulation (2008)

[17] See for example, C. Osborne, D. Mullan, B. Finlay, “Report of the Fairness Committee to David Brown, Q.C., Chair of the Ontario Securities Commission” (September 4, 2004)(“Osborne Report”); See also the Cory/Pilkington Report, supra note 7 ; Allen Report, supra note 4; Five Year Review Committee Final Report: Reviewing the Securities Act (Ontario) (Toronto: OSC, 2004) online: Ontario Securities Commission

<http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/Regulation/FiveYearReview/fyr_20030529_5yr-final-report.pdf>

[18] Osborne Report, Ibid. at 17.

[19] Osborne Report, Ibid. at 17.

[20] P. Anisman, “The Ontario Securities Commission as Regulator: Adjudication, Fairness and Accountability”, in A.A. Anand & W.F. Flannigan, Conflicts of Interest in Capital Markets Structures , Toronto, Carswell, 2003, p. 131-139; D. Johnston & K.D. Rockwell, Canadian Securities Regulation , Toronto, LexisNexis, 2006, p. 124-127.

[21] Provincial/Territorial Council of Ministers of Securities Regulation, 2007 Annual Progress Report , online: Provincial-Territorial Securities Initiative <http://www.securitiescanada.org/2008_0122_progress_report_english.pdf>

[22] For more details, see http://www.financeandtaxtribunals.gov.uk/financialServicesandMarketsTribunal.htm .

[23] See, generally, C.Ford, “Principles-Based Securities Regulation” Research Report submitted to the Expert Panel on Securities Regulation (2008).

[24] While this criticism is often made, it may not be substantiated. See Jackson, supra note 17 , who highlights Canadian enforcement actions, inputs and outputs are relatively comparable to the U.S., when appropriate deflators are taken into account.

[25] Janis Sarra, “Proportionate Regulation” Research Report for the Expert Panel on Securities Regulation (2008).

[26] Criminal Code R.S., c. C-34, s. 718.1.